NICE numbers: trends in recommendations should prompt a review of NICE

With the Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS) being renegotiated, Leela Barham looks at the trends in National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendations and asks if there should be a different review of NICE as part of a successor PPRS.

Analysing NICE’s track record

NICE regularly produces statistics relating to the recommendations made as part of its Technology Appraisals (TAs). Its standard summary table gives an overall picture of how often NICE says ‘yes’ or ‘no’. The latest summary statistics run from 1 March 2000 to 31 December 2017 and show that NICE says yes more than it says no: 57% of recommendations were positive. The figures include its optimised and Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) recommendations, too, to reach the headline 81% positive rate.

NICE also produces a Word document covering the recommendations reached. Analysis of this allows an exploration of trends over time, which is something missing from its website.

More options for NICE recommendations

NICE committees now have a greater range of options for their recommendations; they can say ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘maybe’. (It is only in Research recommendations that NICE suggests that a drug is used as part of further clinical research, which could help them make a decision on wider use in the future). They can also ‘optimise’ (industry uses the term ‘restrict’) a recommendation suggesting where and when in a pathway a drug should be used, narrowing use within the licensed indication. There are variants specifically for cancer drugs, too, with the option of recommending use on the CDF (another may be style of recommendation, offering funding on a time-limited basis until a future review by NICE), both optimised and as per the licensed indication.

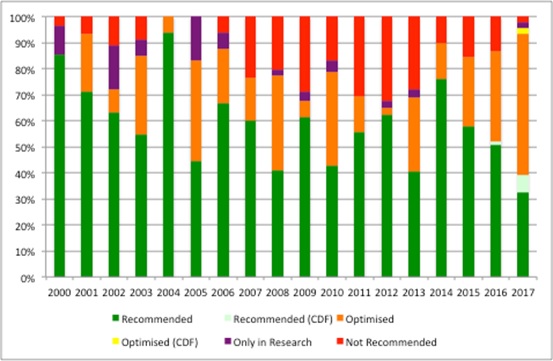

The committees are making much more use of some of the nuanced recommendations over time; 26% of NICE’s recommendations made in 2017 (up to September) were 'recommend' and 43% 'optimised'. That’s a shift from the past (Figure 1).

Figure 1: NICE recommendations per year, March 2000 to September 2017

Source: Analysis of NICE data

No NICE recommendation

NICE has never looked at every new drug on the market; instead it looks at those that meet certain criteria and are deemed worthy of its scrutiny. These days NICE may plan to scrutinise a drug, yet cannot because the manufacturer doesn’t provide a submission. In this case there are two stages; first a Single Technology Appraisal (STA) is suspended and then eventually formally terminated. Suspended STAs can be re-started if a company submission subsequently comes in.

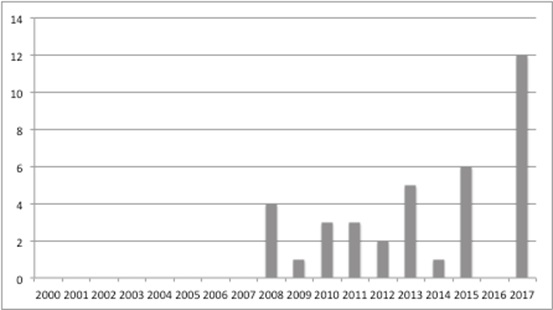

NICE statistics allow analysis of the terminated TAs (Figure 2) and suggest a marked rise in the number over time.

Figure 2: Terminated appraisals at NICE, March 2000 to September 2017

Source: Analysis of NICE data

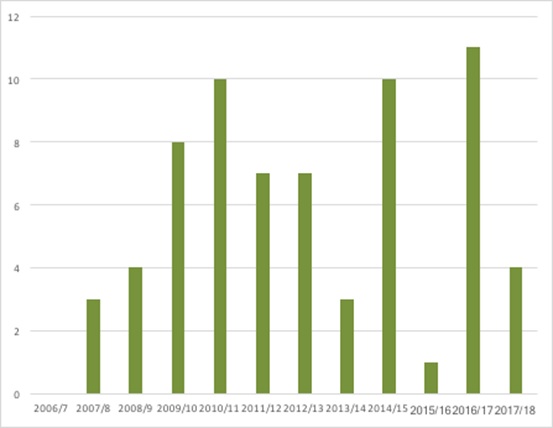

A freedom of information request allows an understanding of suspended STAs (up to August 2017) (Figure 3). While it’s not necessarily the case that these will all be formally terminated, if they were, they’d add substantially to the terminations total.

Figure 3: Suspended NICE STAs, 2006/7 to August 2017

Source: NICE Freedom of Information request response, August 2017

The need to dig deeper

These numbers raise questions and don’t provide answers; why is NICE now less likely to give a wholehearted ‘yes’? Why are companies less willing to participate in the NICE process?

Much could be done to explore what lies behind the trends and which side bears the blame (and the work done in the past and available in academic literature on the drivers of NICE decisions could be updated too).

It may be companies and the nature of their products, or NICE, or more likely a combination. Not to mention tracking what goes on after NICE has made its pronouncement and whether patients get access with the implications for their health and wellbeing which is only partially covered in work done for the Innovation Scorecard and other efforts on access.

A review of NICE?

One option is for a successor to the current PPRS to include a review of the methods and processes of NICE’s work. The PPRS includes access, and has provisions relating to NICE. There are good reasons, not just related to NICE numbers, to review NICE as a whole because there have been changes that, by themselves, are arguably marginal, but collectively may be important to look at the impact on access. For example, looking at the success, or otherwise, of early scientific advice and patient input.

Further changes are afoot at NICE and, in time, it will be worth exploring these too. They include the impact of proposals to speed up NICE’s work by doing more before committees meet, moving the first gateway for Patient Access Scheme approval to NHS England from the Department of Health, as well as the budget impact test and associated negotiation for access on those drugs that look likely to cost more than £20 million a year in any of the first three years after launch.

Threshold may matter more

The small changes at NICE may pale in comparison, though, if the threshold its committees use to judge when a drug goes from being cost effective to too expensive changes. The PPRS included a statement that the ‘basic cost-effectiveness threshold…will be retained’. That’s £20,000 to £30,000 per Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY), although NICE does recommend use even with higher numbers if it’s an end-of-life treatment or an orphan drug.

If the basic threshold is reduced, as some have argued it should be, the result could be more ‘nos’ and more optimised recommendations, but also an increase in non-submissions. Both are worrying for many; patients and clinicians typically want access, industry certainly does, and Government is unlikely to want to feel more pressure from an industry that is considered a priority for the UK economy as it approaches a post-Brexit era. It also leaves a vacuum and the potential for variation across the NHS when NICE doesn’t provide its view and that was part of the reason NICE was introduced in the first place.

Time will tell for how nice NICE will be in the future.

About the author:

Leela Barham is an independent health economist and policy expert who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally. Leela works on a variety of issues: from the health and wellbeing of NHS staff to pricing and reimbursement of medicines and policies such as the Cancer Drugs Fund and Patient Access Schemes. Find out more here and contact Leela on leels@btinternet.com.

Read more:

Has the UK been the best place in the world to invest in life sciences?