Early Access: the ground rules for communicating with physicians and patients

How should medical departments, advocacy liaison leaders and communication teams in pharma companies deal with demand for early access to investigational medicines?

The last few years have seen a rapid increase in the number of requests for compassionate use of unlicensed medicines, and this phenomenon is one that no pharma company can ignore.

One of the main reasons for this development is the rise of increasingly educated, empowered patients and proactive patient advocacy groups, who have used the internet and social media to forge networks of interest. These groups now have a considerable voice in lobbying for access to medicines, and are increasingly accepted as key stakeholders in the regulatory process.

The most striking examples of this can be seen in life-threatening and/or rare diseases, such as with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD). Over the last few years, patient advocacy campaigners (many of them parents of boys suffering from DMD) have campaigned for expedited access to drugs, and, indeed, have become a force to be reckoned with, changing the way that endpoints and outcomes are viewed. Although not the only factor, the influence cannot be ignored and as evidence of this changing dynamic, the first drug for DMD received conditional approval from the European regulator the EMA in August of this year.

This is just one example of how drugs still in development are being demanded. Another, very current and indeed urgent, example is the Ebola epidemic in West Africa. In recent months the World Health Organisation and the US regulator the FDA have had to make special exemptions to allow unlicensed drugs – some of them never tested in humans before – to be given to patients infected with the often deadly virus, as no other treatment options currently exist.

The Ebola case has spawned much debate, and it is an extreme case. However any company with a drug in clinical trials – and especially those operating in disease areas with limited or no treatment options – should now expect, and proactively plan for receiving, requests for early access.

It is clear that the best route to enable eligible patients to access medicine is through the established local regulatory approval processes and pursuing commercial availability of that medicine. However, quite often there are patients who are facing serious and life-threatening circumstances who are not eligible to enrol in a clinical trial, and cannot wait for commercial availability, yet who may still benefit from access to an investigational medicine. Thus, pharma companies need to balance requests for treatment with the need to protect patient safety and continue the drug development process.

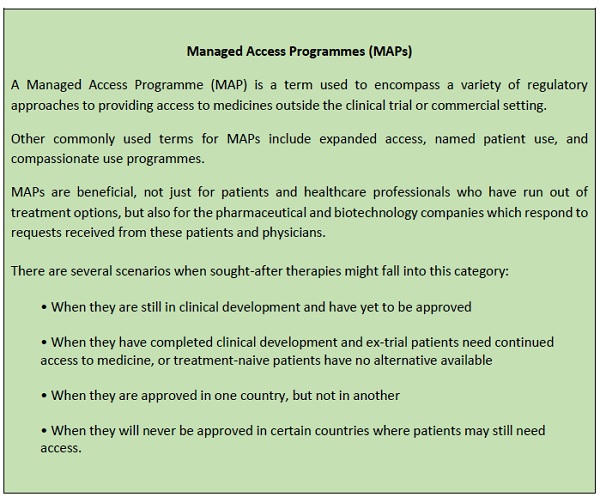

As a result, the question of whether to grant early access, and how to do it, is extremely important and needs careful consideration. For the purposes of this article, let's assume your company has an early access programme – also known as a Managed Access Programme (MAP) – already set up.

In this article, I would like to address the next important step: how to successfully interpret the guidance when it comes to communicating about MAPs to the key stakeholders in the disease community.

Promotion absolutely not, Communication yes

There are numerous laws and codes of practice which prohibit the promotion of unlicensed medicines, and this is something that pharma companies are all too aware of. Companies who understand the regulations also know that not all communication about investigational medicines and MAPs is forbidden – they just need to know how to interpret the regulation, and then create a compliant plan of action. In fact, appropriate, non-promotional communication is permitted and legitimate, contributing towards the equitable, consistent and professional implementation of a MAP.

MAPs as mechanisms to provide access to unlicensed medicines are recognised in countries around the world, and encompass a variety of approaches to provide access to medicines outside the clinical trial or commercial setting (see box).

Three principles of MAPs

How can a pharmaceutical company communicate about MAPs in a practical way?

There are three fundamental principles that govern MAPs and are enshrined in the laws governing this approach. Firstly, there needs to be an unmet medical need, i.e., where there are no alternative treatment options available to the patient. Secondly, the process needs to begin via an unsolicited request from a physician. Thirdly, there is often a requirement that it is a treatment for a serious or life-threatening disease.

In terms of communication, this means the product cannot be actively promoted at all. In line with these three principles, pharma companies put a framework in place to allow access to unlicensed medicines, and wait for physicians to make contact.

When physicians make contact, they will be seeking a specific product for their patient with an unmet medical need. Most likely the request will be for a patient with a severe, serious or life-threatening disease with very limited treatment options.

That is the landscape, and companies that put programmes in place to help patients access their medicines must adhere to the rules governing communication about the availability of an access programme for an unlicensed medicine very closely.

The consequences of crossing that line are significant; there have been many high profile, multi-billion dollar fines in the US where drugs have been promoted outside their licence. As well as being unethical, this tarnishes the reputation of companies very seriously.

Compliant communication – a sensible middle ground

In general, there are the two contrasting responses to the guidance and law governing communication surrounding access programmes. On the one hand, there is a very conservative approach taken by many companies, which tend to be wary of communicating in any way. This approach can result in patients missing out on a treatment option, simply because their physician was unaware that there was a legal, ethical way to access the medicine they are seeking.

At the other end of the spectrum, there are companies which do not take heed of the regulations and put others at risk through their actions. Neither of these approaches allows for a safe and effective route for helping patients in dire need who are seeking access via their physicians.

So how can this be done? The main "take home" message is to stay away from anything which is (or could be interpreted as) a claim of safety or efficacy. Beyond that the guidance is less prescriptive, but companies should act in good conscience and stay away from any activities which are, or could even be perceived as being, promotional in nature. With that guidance in mind, here is a quick run-down of what we feel can be done – and how it should be done.

APPROPRIATE AND COMPLIANT COMMUNICATION

1. Corporate communications

Decision-making in this area depends, to some extent, on what a company's normal practice has been regarding corporate communications. When a MAP is initiated, it is legitimate to announce that to the market via a simple, factual press release, in the same way that it would be appropriate to announce clinical trial updates. The key here is the content, which must be non-promotional and concise, with a distribution circuit that is appropriate.

Likewise, if appropriate, there may be a section on the company's corporate website where it is relevant to mention the existence and scope of a MAP. Once these activities have been undertaken, there will be a compliant online presence for the MAP, so that those who proactively search for information will be able to find it.

2. Databases and publicly-available listings

There are certain places where regulatory authorities list information, such as www.clinicaltrials.gov in the United States, which will include details about MAPs. Likewise, in Europe there are authorities, disease associations and societies that routinely list the access programmes that have been made available. When listings are available, it makes the information more accessible via online searches. With this in mind, it is very sensible to make sure you are present on those listings.

In addition, there is a newly-available register of access programmes soon to be hosted at CheckOrphan (www.checkorphan.org), a non-profit organisation providing news and information relevant to rare diseases. This is intended to be a place where any company providing a rare disease access programme can list their details (whether managing the programme in-house, or outsourced to a specialist partner).

The existence of the register will improve transparency for those who are seeking information about the availability of a specific medicine. Visitors will be able to find the new feature as a tab at the top of each page called "Access Programs". Clicking on the tab will take visitors to a listing of access programmes.

REACTIVE COMMUNICATION

The other side of the coin is reactive communication - you need to be prepared for when a patient group, physician, or any stakeholder in your disease area requests information. This will start before you have a programme in place, and will in fact usually be the reason that a programme is initiated in the first place. The request could come in to your medical department, the company administering your MAP, one of your medical reps at a conference, via your social media channels – essentially to anyone who represents the company.

Early access is an area that is often considered a "distraction" and a secondary issue compared to the bigger tasks of completing clinical development, regulatory filing and so on, but in fact this is a crucial early interaction with the very people who are your most important stakeholders. That is why everyone needs to be prepared to respond in a compliant and professional way when asked about early access to the product.

Every company attending a major medical congress should prepare their responses to questions from international physicians regarding early product access. For instance, the ASCO Annual Meeting, held in the US, is the world's largest oncology conference attended by physicians from all round the world who will ask:

"When will I be able to access this drug in my country?"

Without making any claims about the product, it is possible for a medical representative at the company to respond with information about an access programme if it exists, or is planned.

Empowering and educating the patient community about Early Access

In contrast to this situation, there are many countries where patient groups will not be aware that it could even be possible to access a medicine that is currently unavailable in their country. The physician community may also not be totally clear on how the process operates, especially if they are not based at one of the key treatment centres.

This is why it is important to proactively engage with patient advocates and other stakeholders, to educate and raise awareness of early access routes. This is not to replace or take away from clinical trials, but as an option when all other routes have been exhausted.

Conclusion

The benefits of taking time and resources to get your MAP communication right are numerous. Firstly, having a company-wide protocol and script for dealing with enquiries will help ensure that no-one in your organisation is communicating the wrong message at the wrong time. This means programmes can be run with confidence, and without fear of regulations being violated. It also means that as many patients as possible are able to access the medicine which is, after all, the raison d'être of the MAP.

The single most important factor is to 'think ahead'. Companies should decide before clinical trials begin whether or not they will allow early access, and if so, under what circumstances. Building on this, companies should prepare for all the different scenarios where communication is required.

If you do not have that expertise within your company, there are specialists who can advise and guide you through those preparations.

Planning ahead for access requests is not just a very important ethical issue, but also an important business decision. It will require input from departments across your business - including communication teams, advocacy liaison leaders and medical departments. All these internal teams should reach a consensus about how best to manage these demands, and all should contribute to planning and implementing the strategy.

Planning and being prepared in this way changes the dynamic of an access programme from being something that companies put in place because they feel their arm is twisted, to being something that companies can see as an opportunity and privilege.

Relevant documents

FDA - Understanding Expanded Access (Compassionate Use)

Contrasting approaches to early access across the globe (Idis)

About the Author

Holly Lumgair is a strategic services consultant and patient advocacy manager at IDIS Ltd. After finishing her degree in Neuroscience with German and completing a research placement at the Medical University of Vienna, Holly worked for several years as a life sciences specialist communications consultant at a large communications and public affairs agency. Working with a large number of biopharma companies, Holly advised them on their communications strategy and implementation, including PR, marketing and financial communication. She has worked at Idis for over four years, spanning a range of roles from business development through to corporate development activities including forecasting, analysis and new service development. As a passionate advocate for patients, Holly is also involved in forging relationships with patient groups, seeking to understand their needs and support awareness and understanding of Managed Access. Contact her at: hlumgair@idispharma.com

Have your say: Are pharma companies fully prepared for managed access programmes?

Read more from IDIS:

Managed Access Programmes: maintaining treatment access post-trial