Don’t underestimate the potential of new products

John Ansell shows how much better the products launched a decade ago have performed than expected at the time, and considers the dangers of underestimating commercial potential.

In the September 2003 edition of In Vivo, three consultants from Bain & Co declared that:

"The blockbuster business model that underpins big Pharma's success is now irreparably broken. The industry needs a new approach."

In that year there were 67 products with global sales of at least $1 billion on the market with this blockbuster status.

"...in 2006, two more products achieved blockbuster status."

By the following year Bain & Co's forebodings appeared to be underlined by depressing data on the industry's declining ability to develop new products. In its annual review of New Active Substances reaching their first global market in 2004, Scrip listed just 23 new products. (For comparison, Scrip recently listed 47 new products first launched globally in 2013 – more than double that figure!)

Quality as well as quantity

Scrip had further reservations about the 2004 list:

"Unfortunately, 2004 was a particularly poor year in terms of quality as well as quantity".

Scrip considered that four of the new products reaching the market – Tarceva, Avastin, Tysabri and Exanta – were significant therapeutic advances. It was correct on the first three, all of which went on to become blockbusters. But AstraZeneca's Exanta, a product for treating venous thrombosis, was a failure and the company eventually withdrew it from the market. Scrip also considered a further product, Lilly's Cymbalta, as a future, if less novel blockbuster. This prediction turned out to be correct.

The blockbusters that Scrip missed

But Scrip severely underestimated the potential of other products launched in 2004 (see Table). By the following year one additional product, Avastin, had become a blockbuster. It has gone on so far to exceed $6 billion in annual global sales.

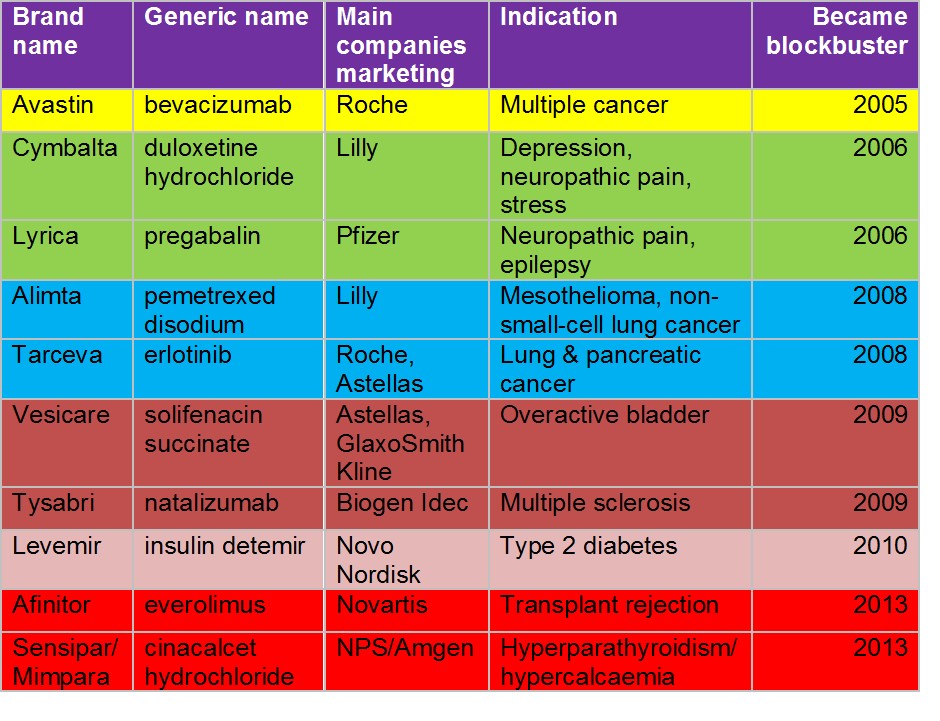

Figure 1: New products first launched globally in 2004 that became blockbusters

Then in 2006, two more products achieved blockbuster status. As well as Cymbalta, which Scrip had correctly predicted as a future blockbuster, Lyrica achieved that status. Both have become huge products, with current annual sales in excess of $5 billion and $4 billion respectively.

"...in 2008, two more products, Alimta and Tarceva, also became blockbusters."

This was by no means the end of the story. Two years later in 2008, two more products, Alimta and Tarceva, also became blockbusters. Alimta's sales have gone on to exceed $2 billion. They were joined by Vesicare and Tysabri the following year and by Levemir in 2010. Levemir's sales just passed the $2 billion mark in 2013. Then in 2013 two further products first launched in 2004, Afinitor and Sensipar / Mimpara, joined the blockbuster ranks.

Thus of the 2004 cohort of just 23 products a remarkable ten, or 43%, had become blockbusters. Now 2004 turned out to be an exceptional year. But the pharma industry's performance at around this time was quite respectable. By my calculation an average of seven products per year launched over the 2000–2006 period have so far graduated to blockbuster status. That has helped to boost the total number of blockbusters despite the depredations resulting from the recent peak in patent expiries. By my calculation there were at least 116 blockbusters in 2012 – almost 50 more than when Bain & Co signalled their doom. And whilst that number is a little down on the peak a few years ago just prior to the patent expiry peak, the blockbuster concept is still very much alive.

The dangers of underestimation

My conclusion is that we should be very careful today not to underestimate the quality of the often unfamiliar new products emerging onto the market. We need to be more alive to the commercial potential of breakthrough products like Alimta and Sensipar that were not widely recognised as having blockbuster potential when they were first launched.

Quality is by no means the only aspect of new products where pessimistic conventional wisdom has become detached from reality. Such misleading underestimation damages the industry. For example, it sends the wrong message to potential investors about the industry's prospects – contributing in my view to the dip in interest in investing in the industry which only over the past year or so has been reversed. It also persuades companies to pursue dubious alternative strategies such as diversifying into generics rather than keeping up the effort on developing new products. If only we sharpen our assessment skills and keep our nerve in developing those new products which merit it, then that strategy will pay off.

About the author:

John Ansell has been has been commercially evaluating products and companies for over 20 years as an independent pharma consultant in business development and international marketing. Since 2012 he has also been conducting such evaluation and due diligence activities as a Senior Partner at the contract research company TranScrip Partners john.ansell@transcrip-partners.com

His recent book Transforming Big Pharma—Assessing the Strategic Alternatives is published by Gower Publishing.

Closing thought: How long will the blockbuster concept remain alive?