UK life sciences: the impact of a cycle of affordability and pricing barriers

Ben Wheatley reviews the changing landscape for drug pricing and offers some pointers for the UK life sciences sector.

The UK life sciences environment is facing significant challenges. Over 10 years of austerity have left the NHS with considerable financial challenges that are being felt by patients, clinicians and by industry. Faced with a government that is unable or unwilling to deliver significant increases to the health service’s budget, NHS England’s (NHSE) CEO Simon Stevens and his team have been forced to look for savings elsewhere.

This coincides with an era of unprecedented innovation as well as an age of exceptional demand. These three forces are coming together to create an unsustainable situation and, as a consequence, a growing number of initiatives that are designed to limit, delay or manage access to new medicines are being introduced.

NHSE and NICE’s introduction of the Budget Impact Threshold, and subsequent victory over the ABPI in the High Court, was a defining moment. The ABPI’s legal challenge, while appropriate, also helped to portray the sector as ‘the bad guy’ in the NHS’s financial fist fight. Despite attempts to create an active and successful partnership with the NHS, the voice and concerns of the sector have been diminished.

The ABPI estimates that this policy alone will lead to one-in-five new medicines being delayed for patients. Add to this other measures that have been introduced over the last few years, or are in the pipeline, such as the plans to limit access to items of ‘low clinical value’ in primary care, the reforms of the Cancer Drugs Fund system, plans to save £300 million through greater use of biosimilars, or the hepatitis C ‘run rate’ system that was employed, and it is evident that the commercial environment is deteriorating.

The real losers in this ‘affordability battle’ are patients. The UK already invests a smaller percentage of GDP on new medicines than other developed countries, while the government’s own indicators show that patients in the UK are much less likely to receive a new medicine within the first five years of launch compared to its European neighbours.

Industry cannot afford to lose the blame game

With medicine pricing already high on the media and public’s agenda, there is a risk that the life sciences industry is blamed as patients in the UK lose access to the next generation of treatments. An ‘air war’ is already taking place and the response from the sector has been slow at times.

Meanwhile NHSE, the Office for Life Sciences and the Department of Health (DH) are taking the initiative by establishing the Strategic Commercial Unit (SCU), which will drive companies to make commercial sacrifices in order guarantee patient access to the newest medicines. Recently, Stevens announced that NHSE had entered into agreement with several companies to secure access to new ‘but expensive’ medicines, ‘securing fair value for taxpayers’.

The suggestion is that the sector is not offering ‘fair value’ and is making unreasonable demands on an NHS that has been starved of funding. This is a believable proposition, because some companies have taken advantage of the system. This leads to unfavourable headlines, broken trust and the perpetuation of an unflattering image of a sector that apparently doesn’t care about the people it serves.

Such a picture is unfair. Life sciences companies channel significant investment and energy in to patient access schemes, joint working initiatives and partnerships with the NHS. The impact of non-medicine-related initiatives on patients’ lives is immeasurable and also invaluable. The 2014 Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS) also underwrites the medicines bill and the industry has already rebated £1.9 billion to the government. While the scheme was designed to take concerns about affordability and availability off the table, it has simply not been implemented effectively.

Companies should feel aggrieved by the diminishing commercial returns they will receive for medicines that have the potential to transform the lives of patients. It is not unreasonable for companies to expect the government to ensure that medicines that are researched and developed in the UK are then also reimbursed and used by NHS patients. However, such concerns do not get a fair hearing when NHSE is framing the debate as one about an industry with high and unreasonable prices on the gamble that companies will simply lower prices and patients will be happy to wait.

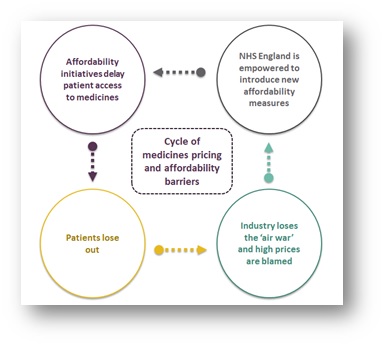

The cycle

Empowered by recent victories and with the media narrative firmly behind it, NHSE may seek to introduce new initiatives to manage and delay access to innovative treatments and technologies. For example, in Next Steps on the NHS Five Year Forward View, published in March 2017, Stevens hinted at his desire to break the NICE funding mandate, while other challenges might include lowering the QALY threshold or introducing new run rates for classes of expensive, but effective, treatments. This would create a cycle where companies are blamed as patients lose out, which is then used to justify the need for new affordability measures.

There is growing recognition that austerity cannot last forever and that the NHS will need substantial funding increases. Some of this should be allocated to securing new medicines for patients, but the danger is that it will be too late and there will be so many barriers and challenges that companies stop looking to the UK as a priority market for launching medicines.

What can the life sciences sector do?

The sector must continue to push back on these developments and work hard to change the narrative. There are four wider points to consider:

- The immediate priority is to secure a positive deal from the 2019 PPRS negotiations. This will form the foundation for business in the UK and, against the backdrop of Brexit, is vital to help develop a positive environment for the future.

- Individual companies and trade bodies should be focused on holding NHSE and the DH to account for policies that delay patients’ access to new medicines.

- Be prepared for a backlash on medicines pricing and work hard to improve awareness and understanding of the ‘value of medicines’ with the public. There’s also work that needs to be done internally. For example, do the commercial teams that are setting global pricing strategies understand the political circumstances of each market sufficiently?

- The sector needs to be much more direct when companies are acting as outliers or when they leverage a product too far. The collective reputation of the sector is being defined by the actions of a few businesses. Failure to speak up means that all companies are viewed with mistrust.

About the author:

Ben Wheatley is an Account Director at Four Public Affairs (formerly ICG).

Previously he was Group Public Affairs Manager at Alliance Boots.

He has an MA in Public Policy from King’s College London and a B.Soc.Sci in Politics and International Relations from the University of Manchester.