Bureaucracy and duplication: the reality of the PPRS

In the fourth in her series of five articles looking at the objectives of the PPRS, Leela Barham focuses on whether the Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS) has delivered on the aim of reducing bureaucracy and duplication.

The PPRS is a voluntary agreement between the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) and the UK Government, represented by the Department of Health (DH) in London. The fourth objective in the scheme is to reduce bureaucracy and duplication as well as any unforeseen burdens on either party over the years of the agreement, 2014 to 2018.

Paperwork is inevitable

The PPRS has been around, in some shape or form, since 1957. Being a voluntary scheme, there is paperwork involved for companies to formally join. According to a freedom of information (FOI) request response from the DH in August 2017, 166 companies are members of the PPRS. Five have left the PPRS, and 128 presentations have been divested from the PPRS too.

At the heart of the scheme is profit control and that means that the DH has always needed information – in an Annual Financial Review (AFR) – to be able to assure itself that the profit of those companies in the scheme stays within the controls agreed.

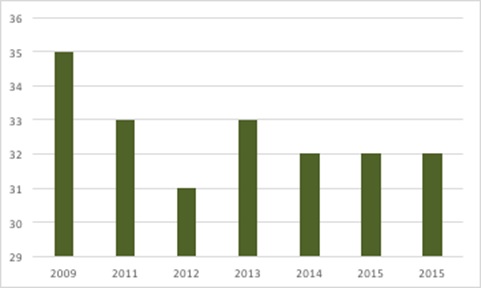

An indicator of the scale of the task of managing the profit control element of the PPRS comes from the number of AFRs. It’s only a small proportion of companies who need to submit AFRs. To see how bureaucracy compares to the previous scheme, data goes back to the start of the previous (2009) PPRS (figure 1).

Figure 1: Number of Annual Financial Reviews (AFRs) under the PPRS, 2009 to 2015

Source: Data from DH and from freedom of information responses from DH. Note that, given deadlines for submissions, data is not yet available for 2016.

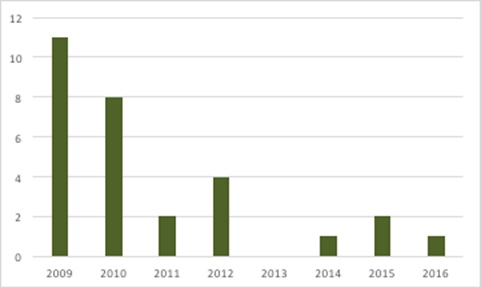

Notifications are also required for launching new medicines and price changes across a company’s portfolio. Although it won’t capture all of the admin and paperwork – by both companies and DH – the number of companies seeking and being granted price increases has been small (there must be a lot of presentations covered by the scheme) (figure 2).

Figure 2: Number of companies with price increases agreed under the PPRS, 2009 to 2016

Source: Data from DH and from freedom of information responses from DH.

Meeting minutes from the DH and ABPI from January 2015 suggested that modulation was less than under previous schemes, so that paperwork burden may be lower than in the past.

New paperwork for the 2014 PPRS

The 2014 PPRS has profit control – just like its predecessors – but also introduced PPRS payments. These are quarterly payments made by member companies, triggered when sales to the NHS go above pre-agreed growth rates.

The introduction of PPRS payments, and the calculations needed to set them, means that the 2014 PPRS has inevitably brought new paperwork requirements. Companies have to supply quarterly sales reports, a company declaration relating to those reports, plus an unaudited, and an audited, annual sales report to the DH too.

There’s new paperwork to do, not just for companies and the DH, but there is also a third-party auditor (BDO, a company that provides audit), resulting in further admin. Companies have to provide BDO with information too. There have been teething issues with this process. More recently, though, as covered in meeting minutes in May 2017, there has been a rollout of online reporting.

The DH generates paperwork relating specifically to PPRS payments, including updates for the payment percentages for the forthcoming years – the 2017 one is the latest – as well as quarterly updates on net sales payments made.

Streamlining paperwork

Although paperwork is inevitable under the PPRS, the 2014 scheme has tried to streamline requirements. For example, it increased the threshold for sales to the NHS that triggers the need for an AFR to £50 million, from £35 million. Around 20% of companies also have to submit full AFR information and have it audited (according to the latest membership numbers and the number of AFRs submitted in 2014). The other 80% have reduced submission requirements and no need for an audit.

The 2014 PPRS also included a review of admin; this has not taken place, according to an FOI response from the DH. Instead, DH notes that both it and the ABPI evaluate the admin burden of the PPRS through six-monthly review meetings.

Duplication

Reducing duplication was another aim of the 2014 PPRS and it is clear that the DH alone conducts the operational activity relating to the core of the PPRS.

The latest scheme also made a commitment that ‘NHS England has agreed to seek to bring to an end initiatives by NHS commissioners to arrange for rebates to be paid by manufacturers to the commissioning body for the supply of medicines with a positive National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) technology appraisal to providers of NHS services in primary or second care’. Yet there is evidence that rebates are still being received, in primary care at least, although it’s unclear if this relates to NICE-approved drugs or not. As the PPRS is essentially a rebate already, further rebates are likely to be seen as duplicative by industry.

Medicines optimisation – making sure the right patients get the right choice of medicine at the right time – has been linked to the PPRS too. The 2014 PPRS was promoted during 14 roadshows across the NHS in England in 2015 as a ‘unique opportunity to ensure patients are getting the right medicines at the right time, less constrained by costs’. Medicines optimisation is also part of the NHS Right Care programme.

The idea is that Regional Medicines Optimisation Committees (RMOCs) operate together to ‘eliminate duplication of activity across England’, according to NHS England. One estimate suggests that the NHS had 600 medicine assessment processes across the UK, given that localities may add their own bells and whistles. With the PPRS covering more than just pricing, and encompassing access and outcomes too, this is another form of duplication.

RMOCs may be particularly useful in addressing duplication when NICE doesn’t look at a medicine; NICE reviews less than half of newly launched medicines. The idea is that one of the four RMOCs can review these remaining new drugs, and the other RMOCs should follow their recommendation. The RMOCs themselves will be overseen by the Medicines Optimisation Oversight Group (MOOG). The Hospital Pharmacy and Medicines Optimisation (HoPMop) team has played a role in shaping the RMOCs too. Collectively they should – in principle at least – stop the local NHS doing much the same thing.

Although the aim is laudable, as the RMOCs were established only in April 2017, it’s unlikely that implementation has made much progress. Plus, even if there is a single source of guidance, the wider NHS may not follow it, particularly as RMOC recommendations have ‘advisory’ status. Variation – and duplication - may not be fully addressed.

And will the RMOCs stay true to the original aims? It has been suggested that their focus has been curtailed and decommissioning – i.e. stopping prescribing – has become a key focus. Even with this, it may still be that the RMOCs represent less duplication than before.

When NICE looks at a drug, the 2014 scheme states that “national guidance in NICE technology appraisals and highly specialised technology evaluations takes precedence…over regional or local guidance…no further qualification, reinterpretation or modifications….” As with much about PPRS commitments, it’s hard to know if this commitment has been met across the NHS in practice.

The paperwork not done

The 2014 PPRS retained some features from the previous scheme, including flexible pricing and Patient Access Schemes (PAS) (most often, confidential price discounts used to help achieve better value for money and NICE approval). Flexible pricing is the option to apply for a price increase when there is new evidence for existing indications, or a company wants a different price for a new indication. NICE would play a key role in assessing the evidence.

The 2014 PPRS notes that the DH was concerned about the ability to plan for price increases, and the impact on NICE’s workload, from flexible pricing. In reality there was no need, as no company has applied. Why no company has tried to use what appears to be – on the face of it – a desirable flexibility within the PPRS, even accepting the paperwork generated, remains an open question.

There was also a provision for a review of both flexible pricing and PAS. That, too, would have involved paperwork, but it might have explored not only why flexible pricing hasn’t been asked for, but also what could be streamlined about the PAS application and review process too. An FOI response from the DH on 4 September 2017 stated that ‘if a review of the operation of the provisions of the 2014 PPRS on flexible pricing and PAS is carried out, it will be initiated not later than two years after the commencement of the scheme. No such review has been triggered’.

One inference is that the ABPI might have missed making a formal request in time, especially as minutes from March 2016 suggest that it requested a review then,. That would have been formally in the third year of the scheme. There was also the interaction with other work; the Accelerated Access Review (AAR) was looking into related issues and there was discussion about the review of PAS and flexible pricing once that reported, but that doesn’t seem to have happened.

The 2014 PPRS, like its predecessor, has a provision relating to reports to Parliament. The DH produced annual reports in the past, but under the 2014 scheme just one report has been produced to date. That was published in April 2014 and doesn’t provide clarity on the operation of the 2014 scheme. According to an FOI response from the DH on 20 June 2017, no date has been agreed for the next report, despite the DH suggesting, in March 2016, that the next one would be published in early 2017. It may simply be a case of the DH having other priorities; a life sciences strategy and consulting on two pieces of secondary legislation can do that.

Unforeseen burdens

There have been changes made as the 2014 PPRS has bedded down. They include an amendment to the payment mechanism so that companies must pay between 2.38% and 7.80% of their sales for the final year – 2018 – of the current scheme. That necessitated discussion between industry and the DH, which, while not paperwork per se, did require time on both sides, probably that neither had anticipated.

One possible burden removed was the cancellation of a planned reconciliation exercise. According to an FOI response from the DH on 20 June 2017, the DH and the ABPI agreed it was not required.

Taking a wider perspective, the prospect of negotiating with NHS England under the budget impact test could very well be a burden, with little upside for the company involved. Under the test, if a new drug has a forecasted budget impact of greater than £20 million a year for the first three financial years, the company must discuss how to manage entry with NHSE, even if it is approved by NICE. That may mean a discount, or phased access, or something else, since it is untested at the moment. It certainly wasn’t likely to have been foreseen by industry at the time that the 2014 PPRS was agreed. The ABPI challenged the change but its request for Judicial Review was denied.

In addition, there are new requirements under consultation regarding the information that the DH may want from companies. Although it is related to the wider market, where there can be issues with shortages and pricing of generics, the DH is pursuing secondary legislation that includes a PPRS price list as well as the option for the DH to ask for a host of other information too. While the DH may take the stance that these are, for the most part, ‘just in case’ powers, companies will want to be prepared in case they are asked to provide more information. That is if they can; there are complexities around transfer pricing for some of the multinationals.

Light touch price regulation?

With just under 18 full-time equivalent staff at the DH working in the Medicines and Pharmacy Directorate – who work on more than the PPRS – it appears that, at least from the DH side, the PPRS takes a light touch. For big companies, it may be quite a bit of work to furnish DH with the information it wants. Small companies have to prove that they are small in order to minimise their paperwork.

Of course, it depends on how you define the scope of price regulation, to decide if the UK approach really has a light touch. If the others who influence price and reimbursement and, crucially, access, are included, the staff at NICE and NHSE, as well as procurement staff across the wider NHS, need to be added in. That may show the true bureaucracy involved.

That line of thinking means that the next PPRS may need to accommodate this wider perspective to ensure proportionality in the regulation of pricing, as well as addressing how far any further bureaucracy and duplication can be cut.

About the author:

Leela Barham is an independent health economist and policy expert who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally. Leela works on a variety of issues: from the health and wellbeing of NHS staff to pricing and reimbursement of medicines and policies such as the Cancer Drugs Fund and Patient Access Schemes. Find out more here and contact Leela on leels@btinternet.com.

Read the previous articles in this 5-part series examining the PPRS:

Part 1: Unstable and unpredictable? The reality of the PPRS