20 People who shaped healthcare in 2014 (Part 4)

In the final instalment of our review of 2014, Andrew McConaghie looks at how patient advocates in rare diseases and 'activist investors' have shaped healthcare – and will continue to in 2015.

Read the first, second and third parts of the review

Part 4:

16. Kyal - CF patient

17. Bill Ackman - controversial activist investor

18. Hans Schikan - chief executive of Prosensa

19. Gopi Gopalakrishnan - social entrepreneur in developing world health

20. Roger Perlmutter - Merck's head of R&D

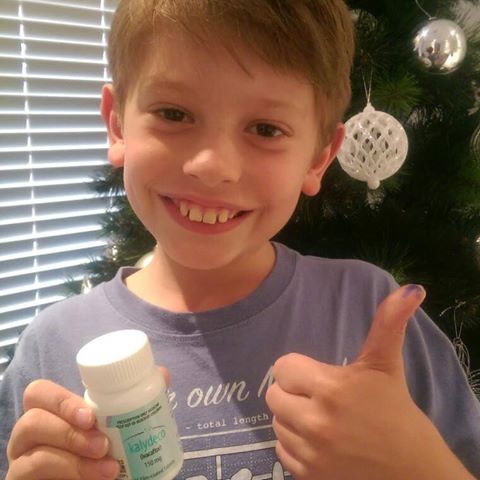

Kyal

The personal story of one boy with cystic fibrosis and battle for access to medicine

After an agonising wait, Kyal finally gained access to Kalydeco in December

Kyal is an 8-year-old boy from Australia with cystic fibrosis (CF) whose family spent 2014 campaigning for access to the groundbreaking treatment for the disease, Kalydeco.

The bravery of Kyal in the face of his disease was shared by his mother Leah Johnston via social media, one of many families involved in the #YesToKalydeco campaign in Australia.

Negotiations over pricing of Kalydeco (ivacaftor) had dragged on since the drug was approved in Australia in July 2013, even though the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) recommend it should be made available to patients with a form of CF caused by the G551D mutation.

The PBAC baulked at the Kaydeco's price tag of A$300,000 a year per patient set by US pharma company Vertex, and refused to pay for the drug.

Over the course of 2014, the #YesToKalydeco campaign gained momentum and support, but health minister Peter Dutton resisted calls for access. The Minster attracted further criticism after implying the social media campaigns were "pushed by the company and their media relations company" – despite most campaigners calling on both sides equally to find a solution.

But by December, the government and Vertex agreed a pay-for-performance deal that should help the 250 eligible CF patients in Australia gain access to the drug - but will also double the amount the Government spends annually on treatments for CF.

The #YesToKalydeco illustrates just how much is at stake for patients with rare life-limiting diseases such as CF – and underlines the responsibility of pharma companies and healthcare payers to develop new models of pricing and payment, such as risk-sharing. Without new approaches in rare diseases, other patient groups will have the same agonising wait as that experienced by Australia's CF patients.

Visit the Facebook page for Kyal's campaign, Kyal's quest for Kalydeco

Watch the YouTube video created by Kyal's mother Leah Johnston in March

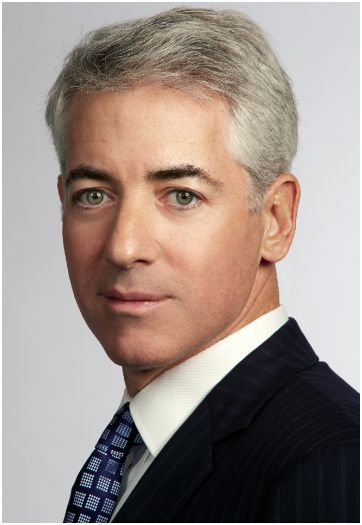

Bill Ackman

Activist investor's alliance with Valeant exposes problems with short term profit focus

The pharma and biotech sectors have long been struggling to reconcile cutting edge R&D – which requires long-term investment, and the demands of investors, who look for short-term returns. This struggle - and the dangers of investor short-termism – have never been more apparent than in the battle for Allergan in 2014.

At the centre of this battle was Bill Ackman – a hedge fund manager who had amassed his fortune by employing aggressive 'activist investor' tactics against companies.

In April, Ackman launched a hostile bid for Allergan in an unusual alliance with Michael Pearson, the chief executive of Valeant. The partners bought a $4 billion stake in the company, and went public with their takeover bid of $47 billion for the firm behind blockbuster 'cosmaceutical' Botox.

Valeant had enjoyed stratospheric growth, but based on a very questionable 'asset stripping' business model: acquiring companies, cutting most of their research operations and squeezing more profits out of existing products.

The rest of the year was spent in an increasingly aggressive and intemperate battle, with Allergan rejecting Valeant's business model as 'unsustainable'.

As the Financial Times put it, the tussle was about more than Valeant and Allergan, it represented a 'battle for the soul' of the pharmaceutical industry. (Read FT article here, subscription required).

In the end, Allergan evaded the clutches of Valeant by running into the arms of Actavis, sealing a deal worth $66 billion. Even though Ackman's original plan was foiled, he still enjoyed a huge pay out, thanks to his large shareholding in the company.

Activist investors and those challenging the status quo within pharma do, of course, play a useful role in keeping companies efficient and shaking up strategy. But when leaders of research companies spend all of their time locked in takeover battles, the short term interests of the market and shareholders inevitably begin to overwhelm all others – including the long-term investment in R&D which the sector needs, and which delivers innovative medicines for patients.

Hans Schikan

Prosensa set to launch first treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy in 2015

2014 was a vintage year for biotech companies, as investor interest in the sector created soaring share prices – but also its fair share of slumps and 'market corrections' when some companies working in the risky field inevitably posted bad news.

Netherlands-based biotech firm Prosensa certainly experienced a rollercoaster 2014, but ended the year in triumph – with its first-in-class drug accepted for filing by regulators, and a multi-million buyout of the company.

The year started very badly when, in January, GlaxoSmithKline announced that it was exiting its partnership with Prosensa to develop the Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) candidate drisapersen. This was because, three months earlier, data from a late-stage trial found the drug no better than placebo in a test of six-minute walking distance.

The drug is part of the class of so-called 'exon-skipping' therapies, which aim to restore the function of a protein called dystrophin that is impaired in DMD. The rare genetic disease affects boys and is characterised by severe muscle-wasting that generally leads to death before the age of 30.

The Dutch firm had been in a race with US-based Sarepta, which had its own exon-skipping drug, eteplirsen, which saw its share price soar as Prosenta's plummeted.

At this stage, things looked bleak for Prosensa, but the reality was that both companies still had to convince the FDA that their drugs were worthy of approval. Now Prosensa looks set to gain approval in 2015, while Sarepta has suffered its own serious setback. While good fortune played its part (as it always does) Prosensa's excellent science and excellent management and sheer tenacity looks to have made the difference.

Hans Schikan has been the firm's chief executive in January 2009. Shickan has 25 years of leadership experience in the sector including, perhaps crucially, at rare disease specialists Genzyme. From May 2004 until January 2009, Schikan took on various roles at the US firm, including head of global marketing and strategic development for its rare genetic disease franchise. In this position he oversaw the launch of various orphan drugs globally, and combined with his clinical insights as a pharmacist, this background stood him and the firm in good stead.

Prosensa began to turn things around through extensive discussions with the FDA and EMA, and secured an agreement to review the drug based on surrogate endpoints, putting the drisapersen programme back on track.

The company was given clearance to start a 're-dosing' programme, giving boys who had participated in earlier trials new doses as part of a new open label trial.

The company also focused closely on finding new ways to prove the efficacy of its drug, these efforts led by Prosensa's chief medical officer and head of R&D Dr Giles Campion.

Among the many technical barriers facing drug developers has been simply measuring levels of dystrophin in DMD patients.

In September Prosensa announced a breakthrough, saying it had developed an "accurate and reproducible" means of measuring protein levels in patients with the condition, as well as those with the similar Becker's muscular dystrophy (BMD).

Then in November, it was Sarepta's turn to announce a major setback: the FDA had concerns about the clinical endpoints used in its trial, which included just 12 patients, as well as the methodology used to measure the effects of the drug on dystrophin.

The difference between the companies' scientific and management processes was clear. In contrast to Sarepta's meagre data, Prosensa has conducted studies involving more than 300 DMD patients at more than 50 trial sites in 25 countries and "has followed clear FDA guidelines", according to comments at the time from Edison analysts Frank Gregori and Mick Cooper.

Another vital component of the success was a stable funding stream, and among Prosensa's sources was a €5 million contribution from medical charity CureDuchenne. Read CureDuchenne's article for pharmaphorum Patient organisations: accelerating orphan drug development.

Drisapersen was filed in the US under a 'rolling submission', which is near completion, and analysts believe the drug could be on the market in the third quarter of 2015.

"It has been an amazing journey," said Hans Schikan in August. "We have learned a tremendous amount that enables us to better understand both the natural history of DMD as well as put the vast dataset we have into context."

Drisapersen will only be able to help a subset of patients with DMD, those who respond to skipping of exon 51, accounting for around 13 per cent. But it is hoped that if drisapersen can prove its worth, Prosensa can expand its use. The firm has seven other drug candidates for other forms of DMD, as well as its preclinical programmes in Huntington's disease and myotonic dystrophy.

If, as hoped, drisapersen is approved, its launch will only be the beginning of a long process in finding a cure for Duchenne. The drug can only slow the progress of the terrible disease in the exon 51, not halt it, so there are many more obstacles to overcome.

In November, having secured a path to approval, Schikan and the company's board agree to a $840 million offer from BioMarin to acquire the firm. BioMarin is a rare disease specialist firm, and has a number of successful orphan drugs already on the market.

The US company will pay the full $840 million price (with two final $80 million milestone payments) if drisapersen gets US approval before May 2016 and in Europe no later than February 2017.

BioMarin is set to maintain Prosensa's offices in Leiden, but it is not yet clear if Schikan will stay on or seek out other opportunities in pharma or biotech. Among the many disadvantages Europe has compared to the US biotech sector is a limited number of experienced leaders in the field, and Schikan is one of the relatively few that can claim an against-the-odds victory among Europe's independent biotech firms.

Gopi Gopalakrishnan

Indian social entrepreneur exports 'micro-franchising' healthcare to Africa

They say that necessity is the mother of invention, and India has shown that a desperate need for cheap but effective healthcare can help develop creative solutions.

The most famous of these is the Aravind Eye Hospital, which has driven down the time and cost taken to perform standard eye surgery (such as cataract removal) without sacrificing the quality of its medical care – so much so that its levels of complications following surgery were half that reported in a UK national survey.

Aravind was made possible by the entrepreneurial spirit of its founder and, in 2014, another dynamic Indian, Gopi Gopalakrishnan, began to expand his own vision of low-cost, high quality healthcare for all.

Gopalakrishnan has been providing non-profit health and reproductive health services in India for more than 20 years, and uses 'micro-franchising' to create a new tier of local health workers.

Micro-franchising works by creating a network of community health workers: given some basic medical training, they then earn a living through consultation fees and taking a small percentage from the sale of medicines. These local workers are trained to measure blood pressure, temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, and can assess electrocardiograms. They then take all these results, transmit them directly to the trained doctor, and assist in the diagnosis and treatment via a video conference link.

Gopalakrishnan's not-for-profit organisation World Health Partners (WHP) has used two of India's largest and poorest states, rural Uttar Pradesh and Bihar as test sites for its services, and has continually expanded the population it serves.

WHP focuses on serving rural and other especially vulnerable communities, where millions still live in isolated poverty. Huge regions with poor infrastructure and scattered populations mean that private providers of health services will not enter the market, requiring an alternative solution.

Over 120,000 telemedicine consultations have been conducted in India thanks to the venture, and millions of patients have been seen by 6,000 franchisees across the two regions.

In June, the organisation took a major step by exporting its model to Africa, bringing its telemedicine and micro-franchising expertise to western Kenya, which faces many of the same problems as rural India.

Read Gopi Gopalakrishnan's blog in the Huffington Post.

Roger Perlmutter

Merck's R&D chief is at the forefront of reinventing Big Pharma drug development

The search for new, faster ways to conduct clinical trials has been gathering pace for some years and, in 2014, Merck's Roger Perlmutter demonstrated just what a difference it could make to development times, and for pharma and patients.

In September, Merck's Keytruda (pembrolizumab) became the first of a new class of cancer treatments, the PD-1 immunotherapies, to gain FDA approval. Its first licence is in advanced melanoma, but it and its rivals are expected to eventually become the mainstay of treatments in a broad range of tumour types.

Not only is the drug a remarkable advance in itself, but its development process could also be a 'game changer': it took just three-and-a-half years from the beginning of phase I trials to its FDA approval, a massive reduction on the average development time.

Keytruda's approval goes some way to restoring Merck's erstwhile reputation as a centre of outstanding science and corporate efficiency, and Perlmutter has been credited with this renaissance.

Perlmutter had built his reputation as an R&D leader with 11 successful years at Amgen, but his appointment to the Merck post in March 2013 was his chance to take the reins at one of the sector's biggest companies. His appointment was in fact a sort of homecoming, as Perlmutter had previously served as head of basic research and pre-clinical development at Merck.

Key to his success with Keytruda has been in a strong prioritisation of the drug within Merck, with Perlmutter seizing resources from within the corporation to accelerate the drug's progress.

He decided the best way to accelerate development was not to advance the drug to phase II – the most obvious step – but instead to expand the existing phase I trial of the drug, broadening it for use in a variety of different cancer types.

Merck's success is of course very much reliant on close collaboration with the FDA, through the Breakthrough Therapy Designation. This process goes above and beyond previous fast-track procedures at the FDA, with the agency's head of oncology Richard Pazdur also credited for his leadership.

There is no single 'magic bullet' involved in Keytruda's speedy development and approval, rather a series of bold tweaks to the process. Breakthrough designation allows weekly contact between a company and FDA reviewers, who give feedback on safety and efficacy as well as manufacturing processes – taking on all the possible bottlenecks simultaneously, rather than in sequence, as has been done traditionally.

Companies can also employ rolling submission of data to the agency, rather than having to wait until all the data is ready before presenting it to the regulator.

The success of the Breakthrough route has helped make 2014 an exceptional year for the industry: the FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research approved 41 novel medicines in 2014, a very substantial rise of 14 compared to the year before. That tally puts 2014 second only to the all-time high reached in 1996, which saw 53 drugs approved.

The sector has changed enormously since 1996, and 2014's approvals will now be judged much more closely on their clinical performance and safety profile once on the market. 2015 may well see a sea-change in how pharma negotiates its prices in the US as well. But if the sector's leaders can get effective new treatments onto the market much faster, the industry will save billions, and maintain its profit margins in the face of harder bargaining from payers.

20 People who shaped healthcare in 2014 - the full list

1. Pete Frates – the man behind the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge

2. Barry Werth – author of The Antidote

3. Steve Miller – Express Script's scourge of Sovaldi and pharma's high prices

4. Sir Paul Nurse – British science leader and critic of Pfizer's bid for AstraZeneca

5. Emile Ouamouno – Ebola's 'patient zero'

6. Margaret Chan - head of the embattled World Health Organization

7. Joep Lange and Jacqueline van Tongeren - HIV/AIDS activists killed in the MH17 tragedy

8. Mark Reilly – GSK exec at centre of China corruption scandal

9. Robin Williams - a much-loved entertainer succumbs to severe depression

10. Simon Stevens – chief executive of NHS England

11. Chris Viehbacher – Sanofi chief executive pushed out by boardroom conflict

12. Susan Desmond-Hellmann – new chief executive of Gates Foundation

13. Larry Page – Google leader looking to revolutionise healthcare

14. Jonathan Gruber – US health economist

15. Atul Gawande – author of Being Mortal & What Matters in the End

16. Kyal - CF patient

17. Bill Ackman - controversial activist investor

18. Hans Schikan - chief executive of Prosensa

19. Gopi Gopalakrishnan - social entrepreneur in developing world health

20. Roger Perlmutter - Merck's head of R&D

(See above for Part 4)

About the Author

Andrew McConaghie is pharmaphorum's managing editor, feature media.

Contact Andrew at andrew@pharmaphorum.com and follow him on Twitter.