VPAS: Achievement so far on objectives for patients

The UK has a voluntary agreement that was struck by the government and NHS England (now referred to as NHSE&I) with the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) in 2018, which governs pricing for branded medicines and offers commitments on access. The full deal is set out in the 2019 Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS). The deal is just the latest in the long history of voluntary agreements reached in the UK. With the current deal two years into the five-year agreement, Leela Barham takes stock on each objective, starting with the first objective that relates to patients (spoiler alert: not much).

The VPAS dedicates Chapter 3 of the agreement to the mechanisms to deliver on the objectives for patients. These objectives are to:

- simplify, streamline and improve access, pricing and uptake arrangements for cost effective medicines; and

- deliver faster adoption of the most clinically and cost effective medicines with the aim of improving patient outcomes.

The ways that the VPAS sees these being delivered are via a number of different areas of activity.

Enhanced horizon scanning

The NHS already has mechanisms to find out what’s coming down the pipeline. So the VPAS sought to ‘enhance’ these activities.

The VPAS talks about a shared ambition for complete and accurate information about the products coming soon. This specifically includes the clinical, financial and service planning information. UK PharmaScan is the tool used.

The VPAS committed NHSE&I, ABPI, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and others to work together to establish an approach for regular review of horizon scanning.

Whilst the Scheme set out to agree ‘success factors’, subsequently renamed metrics, there isn’t yet a published metric that covers enhanced horizon scanning. A potential metric has been discussed by the DHSC and the ABPI – a draft metric related to proportion of new TAs with PharmaScan presence two years in advance – but that hasn’t made it to the first metrics tracker report set out July 2020.

What you can tell from public sources is that UK PharmaScan website has been overhauled to help improve usability and navigation and has also added a section to its website about VPAS. A joint horizon scanning platform, with the Accelerated Access Collaborative, was reported to be in train in June 2019 meeting minutes from the Collaborative. Operational review meeting minutes also suggest that the working group on this had to stop work due to COVID-19 and needs to restart. So not much progress on the substance of improving horizon scanning, at least on the basis of public information.

Improving engagement and evolving commercial flexibilities

The VPAS recognises that there already was engagement between the NHS and industry and other bodies, so improving these was the aim. Name-checked are ambitions to improve multi-agency learning, early company engagement with the NHS and more proactive case management.

What this translates to at an industry level is using the pre-existing forums such as the Life Sciences Council (LSC), the NICE Implementation Collaboration (NIC) and the Accelerated Access Collaborative (AAC).

It’s tricky to find out about the work of the LSC. At the time of writing the LSC webpage held nothing further than the name. Operational review meeting minutes instead focus on PAMP (the Patient Access to Medicines Partnership), which the BIA describe as an expert sub-group of the LSC. PAMP met in July 2019 according to the BIA. There doesn’t appear to be any public website from the government that explains PAMP or provides any records of who they are, or what they’re working on. The government has been asked in Parliament for more on PAMP. A 11 March 2020 response suggests that there will be a summary of the PAMP discussions ‘in due course.’

Tricky too to find out about the current work of the NIC. What is available is from when the work initially started, back in 2013.

It’s much easier to find out about the work of the AAC. Much of their work is supported by a new team working within NHSE&I. The original Collaborative was set up in 2018 and with a refresh of its work completed in 2019, it’s now described by government as the umbrella organisation for UK health innovation.

The AAC website outlines how, from April 2019 to December 2019, the Collaborative has provided access for over 400,000 patients to 26 late stage innovations. These 26 innovations are varied but do include some medicines; PCSK9 inhibitors and cladribine as two examples. The Collaborative is also able to demonstrate uptake trends in some areas too with a dashboard; a snapshot is available from the Collaboratives website but it seems that the full web platform isn’t publicly available (or at least, not easily found).

The AAC board includes industry, with Haseeb Ahmad, current president of the ABPI. The board has met three times since the start of VPAS. So it is clear that there is regular engagement between industry and others on the board of AAC, delivering on part of the VPAS commitment.

Reading between the lines, maybe there’s now less need for the other forums? So maybe progress is best seen in light of the quality of engagement that is happening via the AAC rather than bemoaning the absence of engagement by the LSC and the NIC.

For companies, improving engagement translates to a single point of contact with both NHSE&I and NICE and for an unspecified number of companies picked for relationship management. The aim is for more consistency and clarity of advice given to companies. Both agencies were to together develop and deliver a joined-up approach for earlier engagement and case management.

When it comes to engagement at the company level it’s not clear what’s happening from public sources; NHSE&I have stated, as reported in operational review meeting notes, that there is a commercial medicines triage function established. NHSE&I also view engagement as positive. NICE is also reported to have set up a Commercial and Managed Access function. It is clear though that deals are being done. Since VPAS began NHSE has been publicising ‘smart deals.’

The smart deals include an agreement providing access to MS treatments Orkambi, Symkevi and Kalydeco, an agreement on another MS treatment, ocrelizumab, a programme to eliminate Hepatitis C, deals on low-cost versions of adalimumab, CAR-T therapies, pembrolizumab for lung cancer and the first treatment for spinal muscular atrophy, nusinersen.

Whilst it is unclear if the aims to improve engagement are being delivered upon from the perspective of companies, it is clear that there is much engagement that is resulting in agreements that deliver access and are acceptable to both the company and NHSE&I. To know if engagement has improved an option is to ask companies involved in deals, pre and post the VPAS. Perhaps something like this is in the minds of the stakeholders who signed up to the agreement?

NHSE&I Commercial Framework still draft

Another commitment in the deal was for NHSE&I to produce a new Commercial Framework. But this would only be for the best value propositions to support patient access to cost-effective medicines.

A consultation on a draft of the framework was undertaken from 1 November 2019 and closed on the 10 January 2020. No doubt partly a reflection of the COVID-19 pandemic, the framework remains draft. That rationale is wearing thin though; especially if you take the view that little was likely to change in response to consultation on what amounted to a re-statement of principles agreed in VPAS and the desirability of leaving some flexibility. Flexibility can be useful to both companies and NHSE&I. Uncertainty and its management features too in the framework. It should really be a formality for NHSE&I to publish a final version and would at least signal a commitment to delivering on one of the most objective deliverables committed to in the VPAS.

More NICE appraisals and managing uncertainty

The VPAS made a commitment to more and speedier NICE appraisals. Under the VPAS, NICE has to appraise all New Active Substances (NAS) and significant extensions to marketing authorisations. In recognition that this might take some time to deliver, a commitment was made for meeting this aim by April 2020.

It is unambiguous that NICE has been doing many more appraisals over time; in 2014/15 NICE published 30 appraisals and by 2019/20 they published 53 albeit lower than the peak year of 2017/18 when 77 were published, according to NICE's statistics. But we need to dig a little deeper to find out if NICE is publishing appraisals for all NAS. We can infer that perhaps NICE isn’t yet achieving this at least up to March 2020.

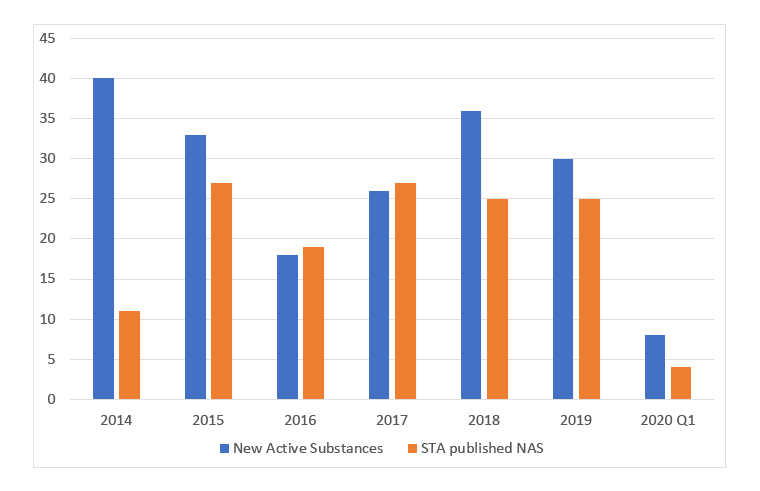

Using data from the metrics that DHSC have published allows a comparison between price applications for NAS (so in essence, the number of these being launched in the UK) with the number of appraisals (Figure 1). It should be taken with a pinch of salt though; it’s not clear if this matches in terms of time periods as NICE appraisals may be published with a lag compared to when the NAS was launched.

Figure 1: Price applications for New Active Substances and STAs published for New Active Substances

Source: Data from the DHSC. (July 2020). 2019 Voluntary Scheme Operational Review Metrics, July 2020.

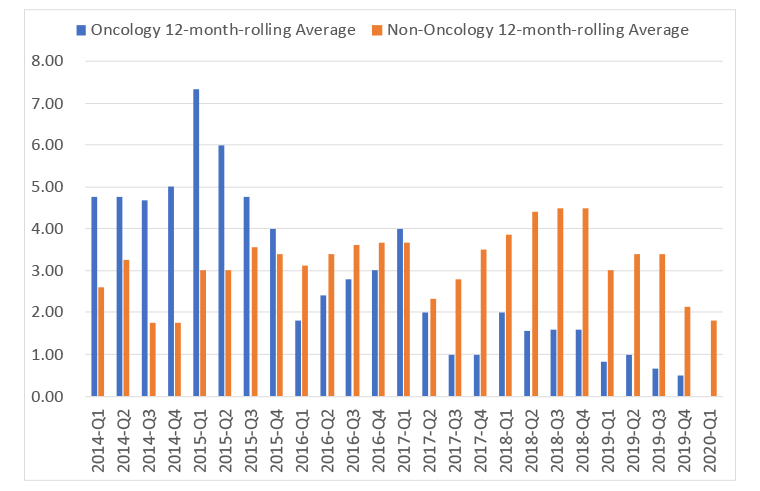

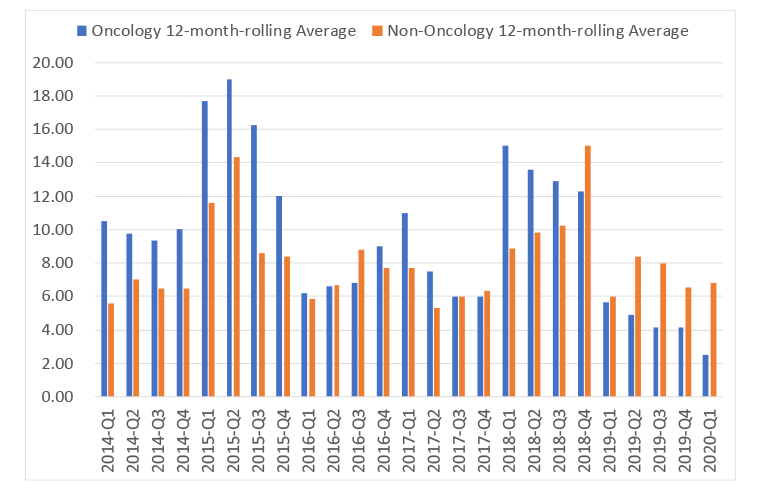

Speed relates to the desire to do appraisals outside of oncology as fast as in oncology, as long as there is sufficient evidence for a rigorous NICE appraisal to be run. Speed is one of the metrics that the DHSC has explored and on a 12-month rolling average basis NICE has not been hitting the target during the VPAS, be that for the first output, or for the final output (Figure 2 and 3 respectively).

Figure 2: 12 month rolling average for time for first output in NICE appraisals in oncology and non-oncology, 2014 Q1 to 2020 Q1

Source: Data from the DHSC. (July 2020). 2019 Voluntary Scheme Operational Review Metrics, July 2020.

Figure 3: 12 month rolling average for time for final output in NICE appraisals in oncology and non-oncology, 2014 Q1 to 2020 Q1

Source: Data from the DHSC. (July 2020). 2019 Voluntary Scheme Operational Review Metrics, July 2020.

Of course, COVID-19 should be considered when looking at NICE’s work; they have not only had the deal with the challenges of staff sickness and working remotely but also the workload of having to produce COVID-19 clinical guidelines rapidly. That NICE has done so much and so quickly should be seen as a success, even if it’s not yet hitting the goals in the VPAS.

The VPAS also committed to NICE scoping and initiating a review of the methods of Technology Appraisal. The VPAS also said that industry and other stakeholders would be active participants in the review, inputting on the scope, participating in working discussions and giving views on the recommendations. A first consultation on this closed on the 18 December 2020. In an effort to limit the impact of such a review, the VPAS stated that any future changes would need to be consistent with improving the health gain achieving by spending on new innovation medicines. It’s too soon to know where this is at since no changes have been concretely identified and predicting the impact will be difficult in any case. NICE is due to publish their plans on 4 February 2020.

The VPAS also included a commitment to a review of the process and methods for the Highly Specialised Technologies programme as well. So far, details of this haven’t come out (or if they have, there are not easily found). NICE board papers from May 2020 do note that the review is ongoing but major changes aren’t likely; rather NICE is aiming for more clarity on the criteria to do a HST, according to their website.

The VPAS also includes a commitment for NICE to clarify its approach to managing uncertainty including briefing committees on the types of uncertainties and ensure committee discussions focus on those areas of uncertainty that have the biggest impact on cost-effectiveness estimates. Uncertainty is a big part of the NICE methods review so progress is being made on this.

Combination pricing

The prices of treatments given in combinations is seen by some, as evidenced by a recent Blood Cancer Alliance report, as a reason why some treatments can’t be recommended by NICE and can’t then be easily accessed by patients.

The VPAS doesn’t make reference to combination pricing explicitly but does acknowledge the challenge in bringing combination branded therapies to market. The VPAS suggests that the DHSC and NHSE&I will support ABPI efforts to help find solutions. Nothing was found on the ABPI website to indicate progress with the ABPI efforts.

Increasing transparency

Visibility of tenders was to be improved as well as the transparency of commercial arrangements agreed between companies and the NHS across the devolved nations.

There already exists a NHS England eTendering service and there is also a tender tool specifically for drugs and pharmaceutical supplies, SELECTT. These are tools available only to registered users and hence it’s hard to know, from outside, whether visibility have been improved for tenders.

Similarly, with the full details of smart deals only known to the companies and NHSE&I, it’s hard to know if the devolved nations are able to access the full details, but you can imagine that this is pretty easily done internally.

Promoting uptake

Arguably the most important of all is a commitment to promoting uptake. This included the intention to invest in the data infrastructure in the NHS in England namechecking e-prescribing as well as improving the Innovation Scorecard. The Innovation Scorecard reports on use of NICE approved medicines in the NHS in England. It also discusses taking a more proactive approach to supporting, understanding and promoting the uptake of the most clinically and cost effective products in England.

The Innovation Scorecard gets regularly updated, with the latest version published on 8 October 2020. It’s not clear what – if anything – has changed in line with the VPAS intentions. It’s even harder to know what has transpired in relation to the commitment for a proactive approach to supporting, understanding and promoting the uptake of the most clinically and cost effective products. Mostly because it’s hard to know what products this relates to and disentangling the impact of VPAS from what was always being done in any case.

A measurable objective is set out to reach the upper quartile of uptake in comparison to comparator countries for five highest health gain categories. A timetable was set out too; to do reach this target during the course of the first half of the VPAS, by June 2021. That means that there is just less than six months left to hit that. No public source has found what the five highest health gain categories are, nor how to measure uptake, and which countries will be considered appropriate comparators.

VPAS operational review meeting minutes show that discussions have been had on reaching the upper quartile of uptake in comparison to comparator countries for five highest health gain categories, but have been difficult. Whilst it is premature to berate NHSE&I for a lack of progress since the target date hasn’t passed yet, it’s looking like it could well be missed.

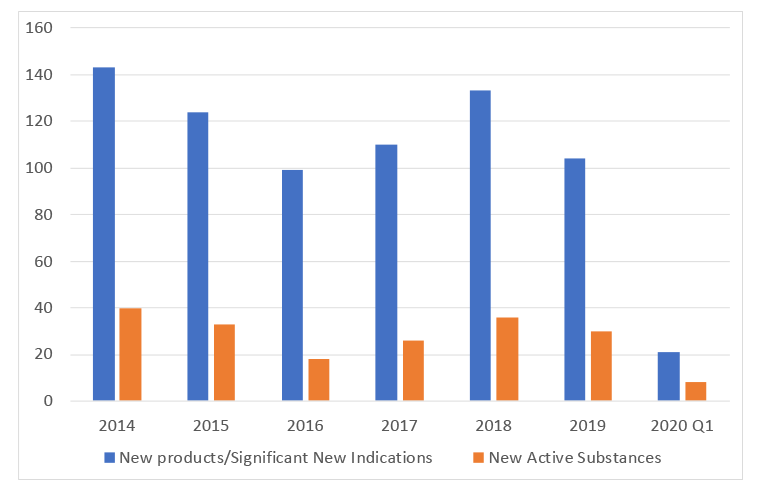

Product launches

One of the published metrics for the VPAS that is relevant to access is product launches. The DHSC’s metrics data from July 2020 has found that applications for prices for new products and NAS shows a decline in new product launches but stability in NAS (Figure 4). The trouble is that this alone isn’t enough to tell us whether patients in the UK have a chance to access all the new treatments that are launched, just those launched in the UK. This leaves an important question unanswered; are there new treatments that have not been launched in the UK?

Figure 4: Applications for prices for new product launches and New Active Substances

Source: Data from the DHSC. (July 2020). 2019 Voluntary Scheme Operational Review Metrics, July 2020.

We can also look at DHSC metric data to help explore if there are NAS that aren’t coming to the UK. Their metric data includes terminated Single Technology Appraisals (STAs) and that shows that there was one NAS in 2019 and one in quarter 1 of 2020 where the STA was terminated. No application to NICE means at best a soft launch, at worst (from a patient perspective) is no launch.

Lack of progress or lack of transparency?

A great deal of reading between the lines is needed to be able to try to understand both what was committed to in the VPAS and whether progress is being made with respect to the objectives for patients. It’s really hard to know if the aim to simplify, streamline and improve access, pricing and uptake arrangements for cost effective medicines and whether the aim to deliver faster adoption of the most clinically and cost effective medicines with the aim of improving patient outcomes are being delivered upon. These seem to be buzz words, not concrete goals.

Public sources seem to suggest progress is limited at best at the end of the first two years of the VPAS, but perhaps it’s because it’s only those in the know that really know. That in itself is a problem, most particularly in the context of delivering of aims for patients. How can patients know if they are reaping the benefits promised to them if there is so little clarity and so little information in the public domain? Industry too will want to see progress, especially with up to £6bn in payments expected over the lifetime of the scheme.

Given the scope of the VPAS, it should also not just be for discussions between those patient groups who are part of working groups, such as those involved in the NICE methods review.

There is still three years to go and that means three years to translate buzz words into better outcomes for patients and to provide an evidence base to help judge the scheme and inform future deals. Let’s hope the DHSC, NHSE&I and ABPI are up for the challenge.

About the author

Leela Barham is researcher and writer who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally, on the economics of the pharmaceutical industry. Leela worked as an advisor to the Department of Health and Social Care on the 2019 Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS).

Leela Barham is researcher and writer who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally, on the economics of the pharmaceutical industry. Leela worked as an advisor to the Department of Health and Social Care on the 2019 Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS).