Paying for value: US state of play

Drug pricing in the US is a perennial topic, which is no surprise given the the US spends more per capita on prescription medicines than any other country. This is not just down to the volume of medication consumed, but also the cost for each, which is often notoriously high. Over the summer the Trump administration made multiple announcements around its plans to lower costs, and yet even with these changes, just a few months on, prices have in fact climbed.

So is there another answer, a system which offers transparency on costs due to set of clear rules and that can be fair to payer, patient and manufacturer alike? With this in mind Leela Barham takes a look at the use of value-based payment models in the US.

Breaking away from the price per pill payment model

In the US there are a number of names for what boils down to a value-based payment model. They are referred to as Value Based Contracts (VBCs), Value Based Agreements (VBAs), Outcome-Based Agreements (OBAs) plus other variants on the same theme. All have in common the concept of paying for value, breaking away from the traditional price per pill payment model.

Support amongst stakeholders for changing incentives

Changing incentives for companies, paying only when a drug makes a meaningful difference to patients in the real world, is something that a number of stakeholders are enthusiastic about.

The US Network for Excellence in Health Innovation (NEIH) – a nonprofit, nonpartisan organisation with over 100 members – has called for value-based contracting to be moved forward. The prospect of paying only when a drug works is intuitively attractive.

According to a survey conducted in March and April of 2018, 68 percent of 127 US payers said that they would consider entering into an outcome-based contract. A third already have direct experience of them.

Industry too are keen on what they refer to as results-based contracts. Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) – representing US innovative biopharmaceutical research companies – has set out it’s stall to promote VBCs including a reality check that counters concerns about such arrangements. According to PhRMA, results-based contracts can lower patients’ out-of-pocket costs, and payers like CVS – a leading US pharmaceutical benefit manager (PBM) - want these types of arrangements, as do companies. They also note that there are barriers to doing these deals.

The current US regulatory environment does cause some issues concerning the introduction of value-based arrangements, with two current areas of focus being the potential for breaching the Anti-Kickback Statute and promotion going beyond the label. Then there’s the practical challenge of tracking patients on the outcomes that are set out within the contract itself, cleaning, validating and analysing that data.

Those barriers might make it hard, but far from impossible. By 2017 all top 10 pharmaceutical companies had used an OBA. Some of these companies are beyond experimentation: AstraZeneca is reported to have more than 35 in place.

It may also get easier with new FDA guidelines published in June 2018 on how companies can have conversations with payers on value-based approaches, part of the Trump administration's blue-print to lower drug prices and reduce out-of-pocket costs issued in May 2018.

Not all stakeholders are convinced

There are still those who are less convinced. Anna Kaltenboeck and Dr Peter Bach – who developed the Drug Abacus to compare prices in the market with a price based on value – have pointed out that outcomes-based contracting might still not deliver the best deal. Instead, they argue, prices should be value-based themselves without all the need for refunds or rebates that make contracting opaque and inconsistent.

Adoption of value-based payment models ramping up in the US

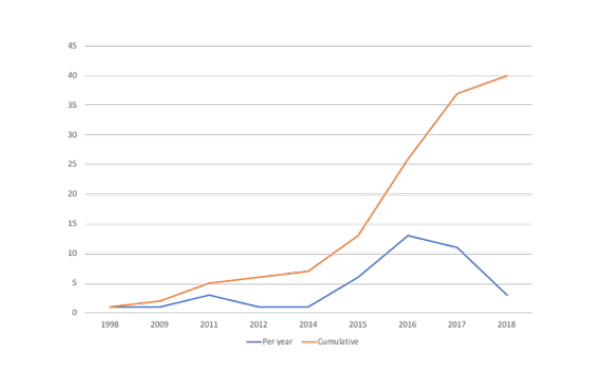

Even with those who doubt the merits of the model, it seems that now is their time, at least in the US. Stisali has been tracking the number of agreements in place in the US. 2016 saw a peak of 13 contracts announced (figure 1), based on contracts in the public domain, many are not.

Figure 1: Value based arrangements in the US, 1998 to January 2018, per year and cumulatively

Source: Data from Stisali. There are an additional three VBAs where no date is available that are not included in the figure. See stisali.com for further information.

Harvard Pilgrim a trail blazer amongst US payers

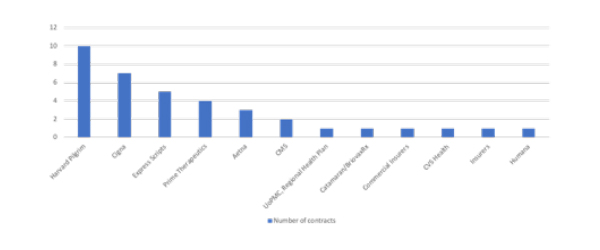

On the payer side, Harvard Pilgrim – a leading not-for-profit health plan – stands out as trailblazer. Stistali found that they had 10 contracts in place between 2014 and January 2018.

Harvard Pilgrim's contracts include a contract with Amgen for Enbrel (etanercept), used to relieve joint pain and stiffness, reduce fatigue and help prevent further damage to joints, as well as Amgen’s Repatha (evolocumab) for hypercholesterolaemia. Under the first Amgen OBA, Harvard Pilgrim will pay according to an algorithm that brings together patient compliance, dose escalation, changes to therapy and steroid interventions. In the second OBA, Harvard Pilgrim won’t pay for patients who experience a heart attack. That deal has been supplemented with a cap on spend on Repatha as well as a rebate related to patient adherence.

Harvard Pilgrim also have deals in place with AstraZeneca – paying less where haemoglobin A1c levels fall below a predetermined goal for patients taking diabetes drug Bydureon (exenatide extended-release), as well as receiving rebates where results from real world use by patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease fall short for Symbicort (budesonide/formoterol fumarate dehydrate).

Other companies have signed agreements with Harvard Pilgrim too, including Biogen, Lilly, Novartis, and Spark Therapeutics.

Harvard Pilgrim is not alone in signing up to OBAs, with Stisali including examples from eleven other US payers (figure 2).

Figure 2: US payers and published outcome-based innovative contracts, 2014-2018

Source: Data from Stisali. See stisali.com for further information.

Value-based approaches don’t work for all drugs

The potential for value-based payment approaches is limited though; it seems that they make most sense when a company is facing competition and needs to differentiate their product with payers, or for high cost drugs when it’s relatively easy and quick to find out if a drug has worked in practice. The value-based approach is not going to work for everything: past experience has seen them mostly in oncology and hematology, cardiovascular and rheumatology, and arthritis.

Early experience will shape the future of value-based payment models in the US

The future of value-based payment models is likely to depend a lot on early experience. Some of the deals struck in recent years are simply too immature to know if they meet the needs of patients, payers and the companies involved.

Those who are not yet fans of the approach may well wait and see just how current deals do; a big indicator is whether or not they are extended or if there will be a return to traditional discounts and rebates, which are familiar approaches and don’t need all the bells and whistles – and therefore hassle - associated with tracking patients.

Experience elsewhere isn’t all good with value-based payment models. The Belgians decided in 2016 to stop doing outcomes-based approaches essentially because they are hard to execute in practice. Even the Italians, often seen as European trailblazers in this area, haven’t been able to generate the savings hoped for. Time will tell if the US can get them right.

About the author

Leela Barham is an independent health economist and policy expert who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally. Leela works on a variety of issues: from the health and wellbeing of NHS staff to pricing and reimbursement of medicines and policies such as the Cancer Drugs Fund and Patient Access Schemes.