How does prevalence affect pricing of rare disease drugs?

New research from CRA looks at the relationship between rarity of a disease and the price countries are willing to pay for drugs to treat them.

High clinical development costs and small target patient populations have often been presented as justifications for high prices of drugs to treat rare diseases. Historically, payers have accepted these factors for reasons including the fact that treatment of rare diseases represents a significant area of unmet need in healthcare and many regulatory agencies have encouraged investment in research in orphan drug development.

In addition, the fact that very few patients would use a product typically means that the cost burden on healthcare systems can be relatively limited. But with many more rare disease drugs entering the market, their financial impact is expanding and payers are increasingly taking a tougher stance on drug pricing, scrutinising clinical data, negotiating rebates and setting budget impact thresholds. They are carefully considering a range of factors including the robustness of clinical data, assessment of clinical and mortality benefit, disease burden and the level of unmet medical need.

Analysis of data of therapies for rare disease

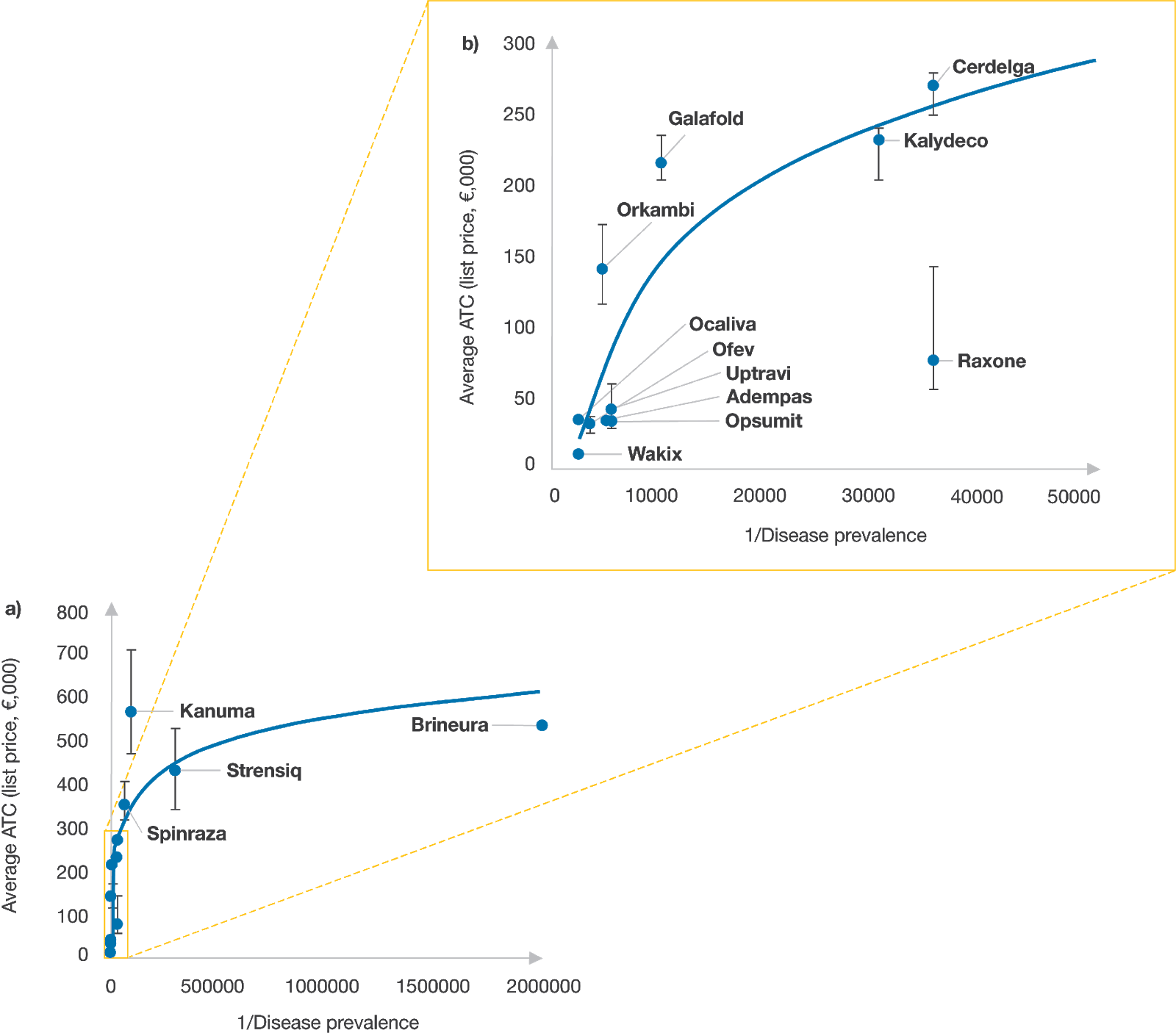

To determine the range of factors payers focus on and the level of consideration they give to each during pricing negotiations for rare disease treatments, we reviewed 15 rare and ultra-rare disease therapies recently approved in Japan, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK. In this effort, we collected information on the average annual treatment cost (AATC) of each drug, assessments of unmet need, payer authority evaluations, and disease prevalence rates.

Diseases with a prevalence of fewer than one in 50,000 people were categorised as ultra-rare and those with a prevalence of fewer than five in 10,000 people as rare. The analysis was structured to take into account disease prevalence rather than incidence as prevalence typically provides a better representation of patient populations, although it is recognised that incidence may provide a more accurate estimate than prevalence for disease states with high mortality rates. EMA prevalence rates served as the foundation for our calculations, however, in cases where these rates differed substantially from literature, we used an average. We used launch list prices of drugs where possible but recognise that confidential net discounts may have been negotiated in France, Italy, Spain and the UK based on prevailing pricing strategies.

Source: CRA analysis

Assessing the impact of disease prevalence

The review focused on three ultra-rare disease products Kanuma, Strensiq and Brineura as well as several approved treatments for rare diseases including cystic fibrosis (CF) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). In general, we found a positive relationship between the list price of a therapeutic and the rarity of the condition being treated – payers appeared to be willing to pay more for products expected to treat fewer patients, but that willingness to pay more did not seem to extend into differences in rarity among ultra-rare conditions.

Kanuma

Kanuma is indicated for treatment of lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D), a chronic disease that impacts approximately one in 90,000 people worldwide and can be life-threatening. Many infants die within six to 12 months of their diagnosis. Given that prior treatment options were limited to a stem cell or liver transplant, Kanuma’s strong clinical profile was a primary factor in pricing decisions. The drug met its primary endpoint in a placebo-controlled clinical trial. Patients treated with Kanuma showed an increase in both survival and growth improvements. After price negotiations, the drug cost in Germany, Italy and Spain was set at approximately €5,900, €6,500 and €8,900 per pack, respectively.

The price could be significantly different in Italy and Spain in part because payers agreed to confidential net price discounts, which is not the case in Germany. Another possibility is that each market calculated disease prevalence differently, impacting the perceptions of unmet need and cost burden. For example, payers in Germany determined the prevalence of LAL-D to be about one in 2.5 million children and about one in 100,000 adolescents. In Spain, the overall disease prevalence range was determined to be between one in 100,000 and one in 120,000 people.

Strensiq

Like Kanuma, the enzyme replacement therapy Strensiq also had a promising clinical profile, which along with unmet need played a major role in payer considerations related to price. The drug is indicated for people with childhood-onset hypophosphatasia, a chronic rare disease that causes symptoms including low bone mineral density, bone and joint pain, skeletal malformations and unexplained broken bones. Hypophosphatasia is fatal in most patients and, in the most severe forms, can be fatal within only days or weeks of birth. Strensiq was approved in Germany, France and the UK based on data including results from a single-arm clinical trial showing improvements in X-ray appearance of the wrists and knees in treated patients compared to historic controls. Payers in Spain, however, required additional clinical data before granting reimbursement.

Prevalence estimates of hypophosphatasia also seemed to play a key role in pricing negotiations; but estimates were inconsistent based on payer location and methods used to estimate patient populations. In addition, the prevalence of milder forms of hypophosphatasia is considerably higher than severe forms – as high as one in approximately 6,300 in European populations.[1] Although the EMA label for Strensiq does not exclude treatment of milder forms of hypophosphatasia, most payers reported focusing on its use in patients with severe forms of the condition when making pricing and reimbursement decisions.

Brineura

There are also cases where the difference between disease prevalence and disease incidence was significant enough to affect pricing decisions. With Brineura, indicated for the treatment of children with Batten disease (or CLN2 disease), this discrepancy was a contributing factor. Although CLN2 disease is an ultra-rare disease based on prevalence (about one in two million), its incidence (about one in 200,000) suggests a higher number of treatable patients. Payers in France considered both of these factors when determining the size of the eligible patient population.[2] The duration of pricing negotiation in France (initial early access via autorisations temporaires d'utilisation nominative [ATUn] AATC was set at €1.2 million) may be indicative of CEPS’ (Comité Économique des Produits de Santé) lack of willingness to pay at the German price level (AATC of €530,000).

Cystic fibrosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension

In cases where there are multiple therapies indicated for the same disease, aligning on price can be more straightforward. Both Kalydeco and Orkambi are precision medicines approved to treat specific mutations that cause CF. Kalydeco was approved first in 2012 for a single mutation in the G551D gene (total prevalence of one in 2,500 in people with CF) and then for treatment of additional CF mutations, increasing the number of treatment-eligible patients. However, Orkambi was approved in 2015 to treat a different and more common CF mutation, called F508del. Given the greater prevalence of the F508del genetic mutation, Orkambi would be expected to treat more patients than Kalydeco, resulting in a lower AATC.

PAH is another orphan indication supported by multiple products, including Opsumit, Adempas and Uptravi. The EMA approved Adempas four months after Opsumit but for two indications- PAH and chronic thrombo-embolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH). However, the EMA estimated only a minor increase in the eligible patient population with the additional CTEPH indication. Ultimately, both rare disease therapies achieved a similar AATC likely because of their comparable launch dates and disease prevalence estimates.

Adempas was also approved for both CTEPH and PAH in Japan in 2014 and 2015, respectively. Interestingly, unlike other therapies available for these diseases, Adempas in Japan achieved an AATC that is slightly lower compared to the AATC in EU markets. Payers in Japan may have been influenced by the potential increase in patient volume and budget impact due to the second indication, and perhaps used the renegotiation to lower the price.

For Uptravi, the indication is restricted relative to Opsumit and Adempas to those who are ineligible for, or who have failed, first line treatment options. As a result, Uptravi achieved higher prices than Opsumit or Adempas in all markets except Japan, where the AATC of Uptravi and Opsumit are similar. While the smaller patient population for Uptravi was likely factored into price negotiations in Europe, it is difficult to quantify its role due to the lack of epidemiology data in first line failure rates.

Conclusion

Disease rarity may be a key driver of price, but payers now often have a prevalence threshold above which they are not as willing to pay for a potential treatment, which may also impact innovative cell and gene therapies in late-stage clinical development.

Overall, payers will likely continue to expect similar price-prevalence relationships for new therapies. To differentiate from competitors on price, drug manufacturers can look to capitalise on several other factors including strong efficacy and safety data and the lack of available treatments to ensure that these are also reflected in payer negotiation strategies.

Manufacturers should ensure that patient populations are well defined and that the patient journey from diagnosis to treatment is well understood to help reduce any uncertainty payers might have related to clinical benefit and budget impact. In addition, companies should select indications with the highest clinical benefit and unmet need and work to collaborate with clinicians, patients and patient advocates who can provide important perspectives that help in pricing negotiations.

About the authors

Cécile Matthews is a principal in the Life Sciences Practice at CRA with 20 years of experience in strategy consulting for the pharmaceutical industry. Her areas of expertise include pricing, reimbursement, and market access globally.

Bhavesh Patel is an associate principal in the Life Sciences Practice at CRA with experience in a range of therapy areas including oncology, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and rare diseases.

Owen Male is an associate in the Life Sciences Practice and advises on key strategic and policy challenges in the life sciences industry.

The views expressed herein are the authors’ and not those of Charles River Associates (CRA) or any of the organisations with which the authors are affiliated.

[1] Mornet E, Yvard A, Taillandier A, et al. A molecular-based estimation of the prevalence of hypophosphatasia in the European population. Ann Hum Gen. 2011;75(3):439-445.

[2] Commission de la Transparence, 2018. Available at: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/evamed/CT-16359_BRINEURA_PIC_INS_Avis3_CT16359.pdf