The importance of collaboration in tackling the ethical concerns of cell and gene therapy

Cell and gene therapies (CGT) offer immense potential for healthcare – opening up countless possibilities for saving and improving lives, which were previously unavailable through existing medical disciplines. As the saying goes, however, with great power there comes great responsibility, and the burgeoning CGT industry now faces the onus of ensuring that medical advancements are made in tandem with ethical progress.

Cell and gene therapy offers new ways of targeting countless chronic and life-threatening conditions, from neurodegenerative diseases to haemophilia. In order to reap the rewards of this potential, while maintaining ethical standards, it will be vital for all those involved in the development of CGT – researchers, manufacturers, and medical practitioners – to engage in an ongoing dialogue about the direction of the industry and the potential effects that treatments could have on patient wellbeing.

Rewriting biology

Since science made its first advancements towards genetic modification, opinions have been vastly divided on the implications of this progress on individual wellbeing and social ideals. The invasive nature of cell and gene therapy has brought about a similar variety of reactions in both the medical and the broader community. While, on the one hand, CGT has the power to drastically improve an individual’s quality of life, the potential benefits should not overshadow concerns around how and why we rewrite a person’s biology, on a case-by-case basis.

Moreover, while the health advantages of cell and gene therapy are myriad, the discipline’s power has expanded beyond the boundaries of purely medical usage. CGTs possess the power to make fundamental alterations to an individual’s biological makeup, and by extension – some would argue – to a person’s very identity. This opens up the potential for targeting more than just medical conditions, blurring the lines between treatment and enhancement.

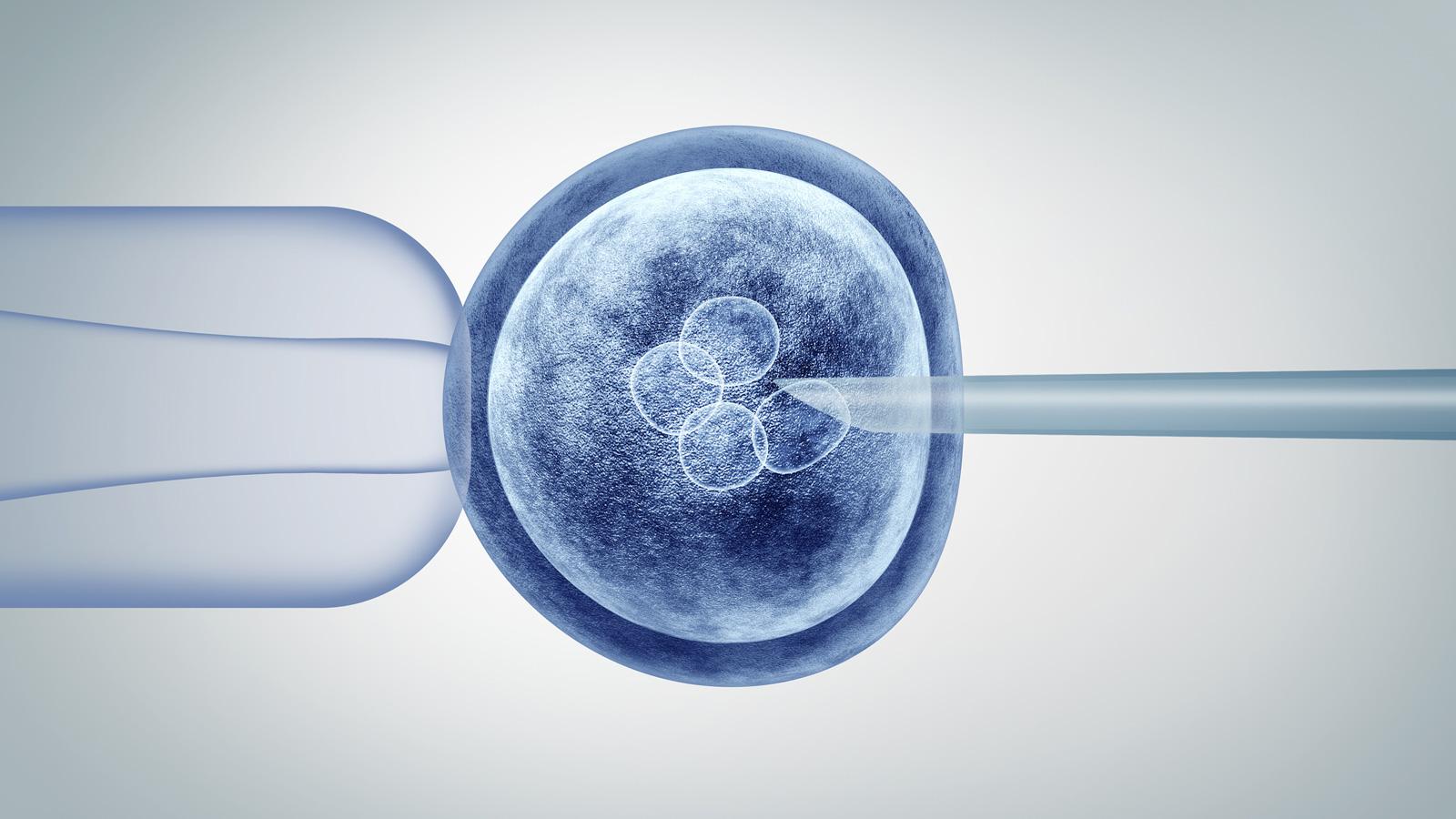

Through future developments in cell and gene therapy, the possibility arises of altering not only the health, but the characteristics of individuals. In particular, we face the possibility of editing the genetic makeup of embryos in line with qualitative ideals such as physical appearance, strength, and intelligence – a pursuit which some are labelling ‘techno-eugenics’. Without an individual’s prior consent, this genetically modifying technology risks compromising our cultural ideals of autonomy. The suggestion that some characteristics are more desirable than others raises the question of who has the right to make such genetic preferences. In order to answer these questions and concerns, and to ensure that CGT continues in an ethically sound direction, industry leaders will need to establish and enhance forums for open conversation, so that any sector progress arises from a variety of perspectives and experiences.

In safe hands?

As with any rapidly advancing medical discipline, the sheer pace of progress for cell and gene therapy means that the development of new medicines risks overtaking safety considerations. Consider germline therapy, for example, where DNA is introduced into the cells involved in reproduction, in order to prevent genetically inherited conditions or diseases. The treatment has the potential to change a person’s biology prior to conception; yet, concerns around the safety of germline therapy have so far prevented its approval in the UK, US, and Europe. Because this form of CGT makes fundamental alterations to the biological makeup of an individual, and because modifications to one cell type are known to have unpredictable knock-on effects for other cells and genes, the long-term impacts of germline therapy are not yet certain.

To ensure that cell and gene therapies can continue to progress, without risk to patient safety, continued dialogue between industry experts will be indispensable. While there’s great value in airing on the side of caution when it comes to new and invasive medical treatments, this hesitancy should be balanced with the potential benefits of CGT. If the sector is to progress, we should be using collaboration and cooperation to recognise solutions, alongside restrictions.

For richer and for poorer

Advances in CGT herald a major step forwards in modern medicine; yet, with the costs of therapies often reaching the £1,000,000s, we must ask ourselves the question of who is likely to benefit from these medical advancements. The danger of economic disparity in cell and gene therapy is well-recognised; what’s less apparent is the solution to this financial divide.

Moreover, the issue affects both individuals and entire regions, with vast inequalities in the levels of funding that nations can invest in healthcare. To reduce this inequality and ensure that cell and gene therapy is available to all on an equal basis, the global CGT industry will need to unite to work towards improved affordability for the treatments. Only through idea-sharing, can supporting manufacturing and logistics technologies arise that will increase efficiency and streamline the development of cell and gene therapies, to the point of making meaningful cost reductions.

While the advancement of the CGT brings with it significant hurdles, these obstacles by no means constitute a deadlock for the sector. Where ethical issues arise, we should strive to find solutions, rather than reject cell and gene therapy on the whole; yet, such solutions can only be discovered through communication. What the industry needs now is continued discussion and increased collaboration to tackle ethical concerns. Without such conversations, we risk sacrificing the full potential of a medical discipline with the power to revolutionise healthcare.