Fatty liver disease: With little early detection, more challenging drug development

For most of my adult life, I had been the typical American fat guy, gaining a pound or two a year and thinking little of it.

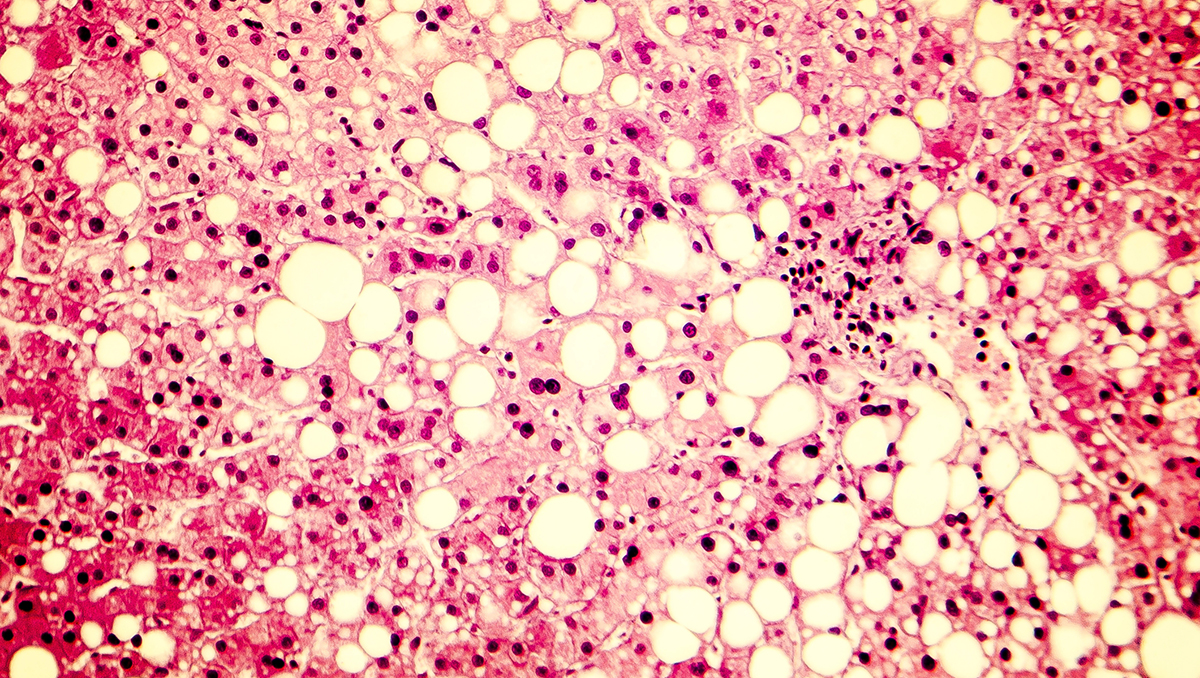

That was until my doctors stunned me with the news that I had cirrhosis caused by non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH, a severe form of fatty liver disease that often has few or no symptoms until very late stages.

I had never heard of NASH, and I was even more shocked when I started searching online and discovered the prevalence of the disease and the tragic reality that there is currently no medical treatment available to cure it.

An estimated 100 million Americans have a fatty liver, and most don’t know it. Of those, 5 million will progress to NASH cirrhosis. The only curative treatment available for cirrhosis is a liver transplant. When cirrhosis complications develop, some will be lucky enough to be listed for a transplant. But nearly 30 percent of those listed will die waiting as too few livers are available for transplantation.

Yet alarmingly, the medical profession does not typically look for asymptomatic liver disease, in part because they don’t have any pills to prescribe to fix it or any simple way to detect it. The first time that most people learn about NASH cirrhosis is when they are told they have end-stage liver disease, like me.

That is a moral failure on the part of medicine.

At the Fatty Liver Foundation, we are formally opposed to that being the standard of care and we are working to make a difference by raising awareness, by advocating for simplification in clinical trial protocols to encourage more patient participation, and by setting up screenings for those at high-risk.

This disease is touching more of us every day. Latinos, for instance, experience NASH at a disproportionately high rate, compared to other ethnicities. Also, NASH is now the leading cause in woman for being listed for a liver transplant.

Cirrhosis is not just an “old drunk guys” disease, a stigma which has long hampered interest and investment in research. Obesity, diabetes, and genetics are the primary drivers, and COVID is about to make this exponentially worse. While it is too soon for hard data, the estimates are frightening when you couple the weight gain during the pandemic to our regularly increasing obesity rate.

The anticipated jump in the prevalence and severity of the disease will put an unbearable strain on the demand for liver transplants, which far exceeds the number available. This puts even more urgency on the investment in and discovery of successful medical treatments to stop or slow the progression of the disease.

But herein lies the dichotomy that medicine has created: By failing to regularly screen to find the early-stage disease, the number of patients who could participate in drug trials is limited. That makes recruitment of patients more challenging. Another hurdle to patient participation is a requirement by the Federal Drug Administration in most trials that the patient have a biopsy of the liver to diagnose and evaluate the stage of the disease. This is an invasive, imprecise, and expensive, and potentially dangerous test that is not part of the usual medical practice. For those patients who have cirrhosis of the liver as, at this stage, there is an increased risk of bleeding from the biopsy. We think there are safer, more accurate alternatives and we urge the FDA to reconsider its guidelines.

Dozens of companies are working at various stages of drug development. Madrigal, for example, has shown some promise with their drug, resmetirom, that dramatically reduces fat in the liver and they are now running a phase 3 global NASH program, to get this drug to registration.

Another company, Galectin Therapeutics, is taking a different approach and is trying to address the disease at the cirrhotic stage. They are using esophago-gastric endoscopies to evaluate the efficacy of their drug belapectin. Endoscopes are routinely used in patients with cirrhosis to detect the presence of esophageal varices, an early complication of liver cirrhosis. The company is also enrolling patients for its global Phase 2b/3 trial, potentially one the largest trials of its kind.

Until there is an available treatment, we NASH patients are left to diet and lifestyle changes for survival. I am one of the lucky ones: I lost 70 pounds and live carefully to try to maintain what liver function I have left. Others are not so fortunate.

Death by liver disease is long and difficult. So much could be prevented with greater awareness of the need for earlier screenings, an investment in promising drug development, and healthier lifestyle choices.

About the Author

Wayne Eskridge, an electrical engineer who worked in software and electronics through a 50-year professional career, was first diagnosed with liver disease in 2010 at the age of 68 and, as a result of his own experiences, he became aware of an acute need for an educational resource from a patient perspective. His desire to help others avoid his experiences led him to the decision to become a patient advocate and to create the Fatty Liver Foundation.

Wayne Eskridge, an electrical engineer who worked in software and electronics through a 50-year professional career, was first diagnosed with liver disease in 2010 at the age of 68 and, as a result of his own experiences, he became aware of an acute need for an educational resource from a patient perspective. His desire to help others avoid his experiences led him to the decision to become a patient advocate and to create the Fatty Liver Foundation.