‘Build back better’ cannot mean longer waiting times for change

Global Blood Therapeutics (GBT) UK general manager Nigel Nicholls discusses the impact of COVID-19 for sickle cell patients in the UK.

If the COVID-19 pandemic has shown us anything, it has highlighted the extent to which health inequity plagues our society. Although the Government, public and health care system have started to wake up to the insidious nature of systemic racism in the wake of the pandemic, many have been left facing tougher situations than pre-pandemic.

The recent build back better plans, the NHS long term plan and subsequent inquiry into Sickle Cell Care by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Sickle Cell and Thalassemia are all indicative of a nation preparing for a future without health disparities. While this national direction is hopeful, many have been advocating for change for years and should not be forced to wait any longer before we tackle inequity.

People want and need change more urgently

We must face the reality that health inequity is not a new issue. Research shows that 10 years ago health inequities faced by marginalised groups were already dire. So, tackling health inequity needs to be a priority now.

One community that has been profoundly affected by the health disparities in this country is the sickle cell disease (SCD) community. SCD is a painful, rare, and debilitating condition and is one of the fastest growing genetic conditions in the UK, affecting 15,000 people. Although anyone can suffer from SCD, it is particularly common in people with an African or Caribbean family background, so the biggest issues around their care are interrelated with systemic racism.

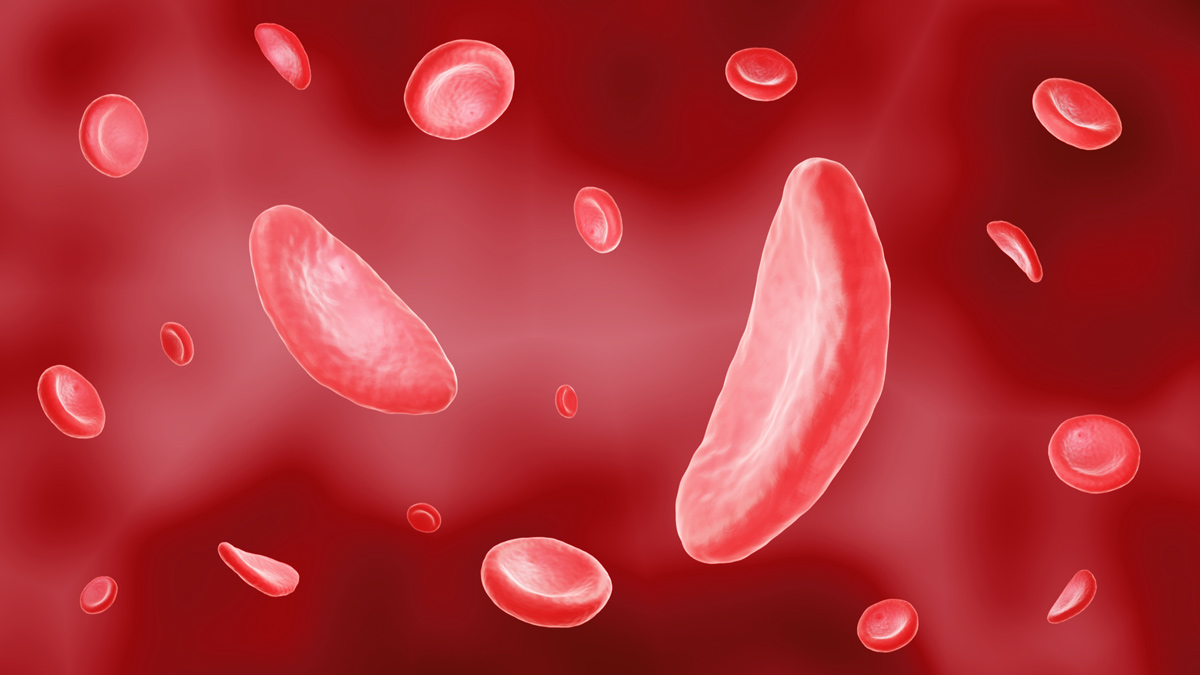

SCD is a lifelong inherited blood disorder that impacts haemoglobin, a protein carried by red blood cells (RBCs) that delivers oxygen to tissues and organs throughout the body. Due to a genetic mutation, people with SCD form abnormal haemoglobin known as sickle haemoglobin. Through a process called haemoglobin polymerization, RBCs become sickled – deoxygenated, crescent-shaped and rigid. The sickling process causes haemolysis (destruction of the RBCs), anaemia (low haemoglobin due to RBC destruction) and blockages in capillaries and small blood vessels, which impede the flow of blood and oxygen throughout the body. The diminished oxygen delivery to tissues and organs can lead to life-threatening complications, including stroke and irreversible organ damage. Chronic organ damage is the leading cause of death in adults with SCD.

Due to the nature of SCD, many living with the disease rely on regular blood transfusions. Blood transfusions are an effective treatment for acute circumstances and some of the severe complications of SCD. However, for this community, the pandemic has exacerbated inequity by increasing the backlog of patients waiting to receive lifesaving blood transfusions. There has been a significant decrease in available blood supply (27.4% less donations) caused by the pausing of blood banks’ services while in lockdown.

It is in crises like this that you can see the stark effects of the pandemic. For the best treatment, patients require blood which is closely matched to their own, however historically there have been lower numbers of African and Caribbean blood donors than the rest of the population. According to the NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) only 1.5% of current blood donors are Black and mixed Black, which has decreased during the pandemic. Post pandemic, 16,000 new donors from the Black and mixed Black communities must be recruited in 2021 to manage the care of many people needing blood transfusions.

"For this community, the pandemic has exacerbated inequity by increasing the backlog of patients waiting to receive lifesaving blood transfusions"

This is a real issue. When speaking to the co-founder and director of operations at the African Caribbean Leukaemia Trust (ACLT), Beverley De-Gale OBE, I was astounded at how the pandemic had impacted one member of the ACLT.

“During the pandemic, appointments have been continually cancelled, re-scheduled and put on hold due to lack of medical staff. For some patients, regular scheduled appointments can act as a security blanket, proving reassurance. Such disruptions in care are frustrating and disheartening, for both them and their families,” she explained.

As a parent of a child with a rare disease, I understand first-hand the distress that the pandemic has caused to the lives of so many carers, parents, and guardians. What is already a stressful, anxiety-inducing experience of attending a hospital appointment can be made worse by severe delays – prolonging an already uncomfortable situation – it can be truly exhausting.

It is commendable that the NHSBT has highlighted the critical need for more Black, Asian and minority ethnic donors, with its United by Blood campaign. However, we must not just fix the immediate problem without looking at the root of the issue. The SCD community faces so many other health disparities such as poor understanding of SCD among HCPs, poor access to care, implicit bias (from clinicians and the public), poor representation within the healthcare setting and poor psycho-social support.

At Global Blood Therapeutics (GBT), we want to shine a light on the inequity faced by those living with SCD. Since it was founded 10 years ago, GBT set out to address the urgent needs of the SCD community through innovation, driven by this historical injustice and lack of understanding and attention given to SCD. With our entrance into the UK and Europe more broadly, we’re committed to supporting this community and helping to shape the change through innovative treatments.

As we begin to recover from the collective trauma of this pandemic - ‘build back better’ cannot mean longer waiting times for change.

About the author

Nigel Nicholls is the UK general manager at Global Blood Therapeutics. He is committed to ensuring that patients understand and participate in the challenges faced in achieving access to new treatments and technologies in the EU.

Nigel Nicholls is the UK general manager at Global Blood Therapeutics. He is committed to ensuring that patients understand and participate in the challenges faced in achieving access to new treatments and technologies in the EU.