A single mutation could make H5N1 flu a human threat

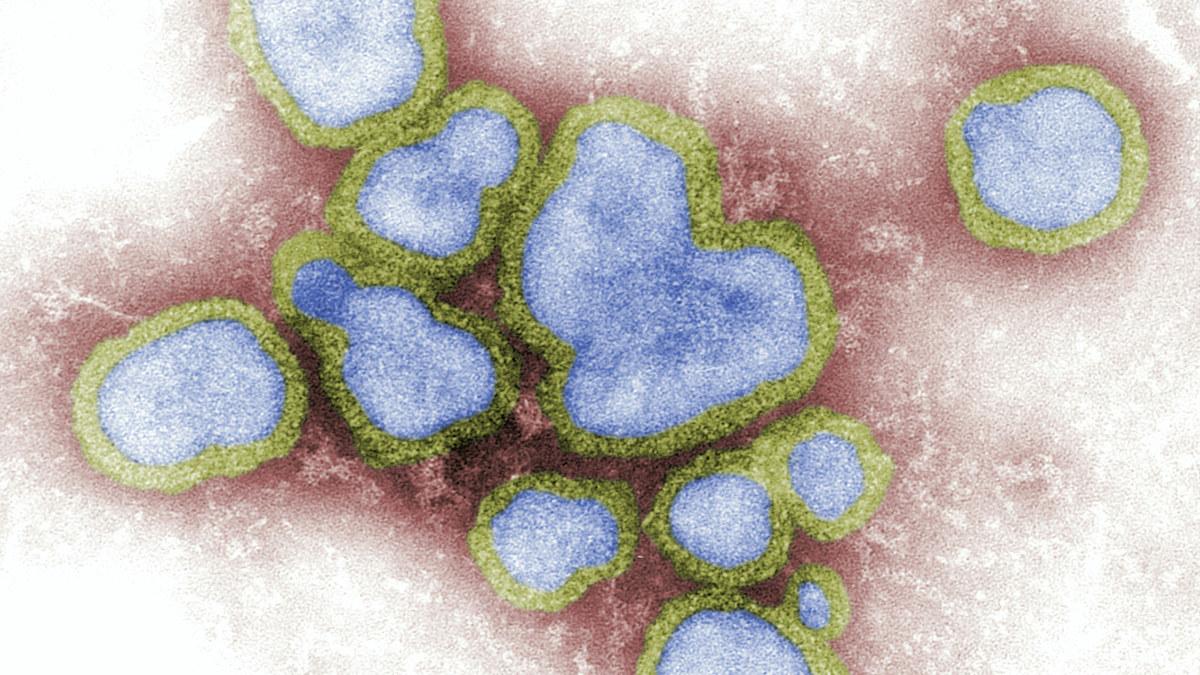

Digitally-colourised, negative-stained transmission electron microscopic (TEM) image depicting influenza A virions

A single mutation in the H5N1 strain of avian influenza that is infecting cattle in the US could make it more likely to infect humans, according to a new scientific paper.

The worrying finding has reinforced the need for close monitoring of H5 flu viruses to try to get ahead of potential mutations that could raise the risk of the emergence of a strain that can be transmitted between humans and cause a major outbreak.

Typically, bird flu viruses require several mutations to adapt and spread among humans, according to the scientists behind the research, led by a group at Scripps Research Institute, which has been published in the journal Science.

The research has focused on a highly pathogenic influenza H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b virus, which has spread widely in cattle in the US this year and has also caused a few cases in humans, albeit mostly with relatively mild symptoms.

Historically, H5N1 have had mortality rates of up to 30%, according to the authors, but there are currently no documented cases of H5N1 transmitting between people. Cases to date have involved people working closely with animals or consuming contaminated food.

The single mutation discovered by the researchers is in the gene coding for haemagglutinin – the 'H' in flu virus designations – a protein that is used by the virus to bind to glycan receptors on the surface of host cells.

Bird flu viruses like H5N1 mainly infect hosts with sialic acid-containing glycan receptors typically found in birds, and the team is concerned that if they evolve to recognise sialylated glycan receptors found in people, they could gain the ability to infect and possibly transmit between humans.

"Monitoring changes in receptor specificity […] is crucial because receptor binding is a key step toward transmissibility," said Ian Wilson, co-senior author and the Hansen Professor of Structural Biology at Scripps.

Receptor mutations alone don't guarantee that the virus will transmit between humans, he stressed, and other genetic changes would likely be necessary for this to take place.

That said, with cases of H5N1 in humans rising, the discovery highlights the need for proactive surveillance of evolution in H5N1 and similar avian flu strains and that even a single mutation shouldn't be overlooked.

Commenting on the discovery, Professor Ed Hutchinson, of the Medical Research Council-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research in the UK, said that the outbreak of bird flu in US dairy herds has provided far more opportunities for the virus to spillover and infect humans.

The new finding is concerning because influenza viruses can acquire mutations and evolve very rapidly.

"Recent studies of the influenza viruses in a Canadian teenager, who has been severely ill for a prolonged period with H5N1 bird flu, implied that the virus had begun to evolve to 'explore' ways of binding more effectively to the cells in their body during the course of an infection," said Prof Hutchinson.

"We do not yet know whether H5N1 influenza viruses will evolve to become a disease of humans," he added. "This study only worked only with purified proteins and did not generate any potentially dangerous viruses, so we also do not know for sure if this mutation has any hidden costs for the virus which might make it harder to acquire."

Nevertheless, he said the research highlights the need for the current outbreak in cattle in the US to be taken extremely seriously and for every effort to be made to monitor the evolution of the virus.