First gene-edited pig liver transplant 'worked for 10 days'

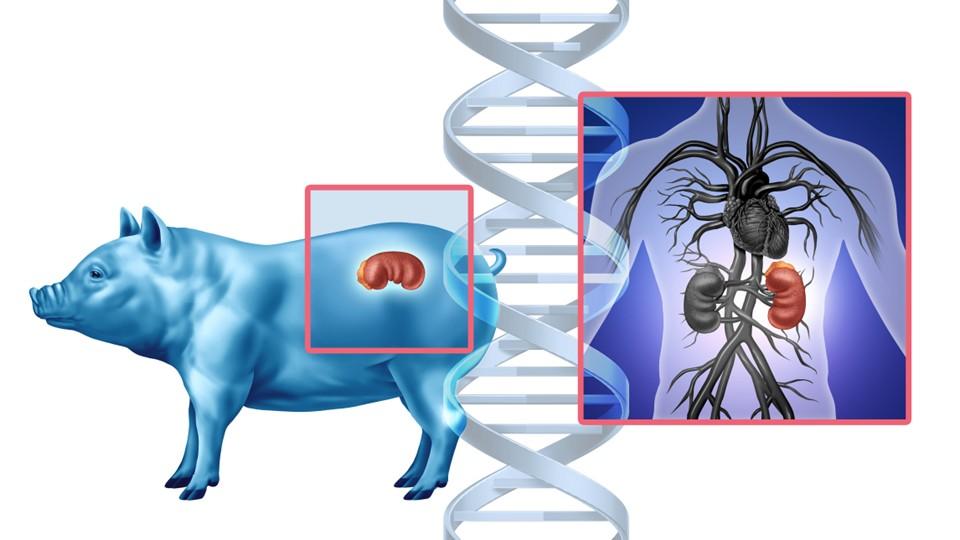

Researchers in China have carried out the first transplant of a pig liver, genetically modified to prevent immune rejection, into a brain-dead human patient.

The transplant functioned for 10 days after the procedure, with no evidence that it was rejected by the recipient over that period, according to the team from Fourth Military Medical University in Xi'an, China, who have published their work in the journal Nature.

The achievement is the latest milestone in the field of xenotransplantation – organs and tissues harvested from animals for use in humans – which aims to solve the problem of a worldwide shortage of human donors. Pigs are an interesting option for liver transplants as their organs have a similar size and physiological function to the human equivalent.

The scientists – who performed the first pig-to-monkey liver transplant in China more than a decade ago – used a liver from a miniature pig provided by Chengdu-based ClonOrgan Biotechnology that had been specially bred to provide organs for xenotransplantation. The animal had six genetic modifications designed to reduce the immunogenicity of the liver and reduce the risk of rejection.

The surgery was carried out at Xijing Hospital in Xi'an, with the transplanted liver introduced alongside the patient's own liver and monitored for signs that the immune system had started to attack it. After 10 days, the experiment was ended at the request of the patient's family.

In the paper, the team notes that, while the xenotransplant was able to carry out basic functions like the synthesis of albumin and the secretion of bile, it is unlikely that it could support the human body on its own for a long period.

The relatively short follow-up period meant that it was only possible to look for short-term alterations in the transplant, but they concluded that "this unique pig-to-human liver xenotransplantation can still provide critical information that cannot be provided by animal experiments alone."

The genetic modifications were similar to those made in recently reported heart and kidney xenotransplants and a cross-circulation study performed at the University of Pennsylvania in the US, according to Professor Peter Friend, a transplantation specialist at the University of Oxford, who was not involved in the trial.

"The presence of the brain-dead donor's native liver means that we cannot extrapolate the extent to which this xenograft would have supported a patient in liver failure," said Friend. "However, this study does demonstrate that these genetic modifications allow the liver to avoid hyperacute rejection."

Importantly, it also showed that a decline in platelet counts that is a recognised consequence of liver xenotransplantation was self-limiting, with counts in the patient recovering within seven days, he added.

Last year, surgeons in the US carried out the first transplant of a genetically modified pig kidney into a male subject, who was able to be discharged from hospital and survived for around two months before dying of an unrelated condition. The organ in that case was supplied by Massachusetts biotech eGenesis.