EMA won't clear chloroquine for COVID-19 without trial data

The European drugs regulator has stopped short of granting widespread use of the drug chloroquine against COVID-19, days after the FDA said it could be used under emergency measures to fight the outbreak.

An unproven medicine against COVID-19, chloroquine and the less toxic hydroxychloroquine are currently licensed to treat malaria and autoimmune diseases such as lupus.

Most of the evidence to support use of chloroquine or the less toxic hydroxychloroquine against the disease comes from a small trial in France.

But the evidence has shown toxicity issues with chloroquine, also used in lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, which can permanently damage the eye and cause vision loss if used in the long term.

While the FDA and the French regulator have granted a wide emergency licence for chloroquine for COVID-19, the EMA has made no such decision, instead leaving it to national regulators to make decisions on implementing such programmes.

In a statement the EMA noted that while studies of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are ongoing in COVID-19, the drugs must not be used outside their authorised uses except in clinical trials or nationally agreed protocols.

The EMA noted that the drugs are vital medicines for patients with autoimmune conditions and warned that they should not be denied access to them because of stockpiling for COVID-19.

Paul Hudson, CEO of France’s Sanofi, has told Reuters in an interview that the company is capable of producing millions of doses of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19.

According to Hudson, the company has made a choice to “overproduce” drugs to ensure hospitals in the Europe and US can keep pace with demand.

Hospital executives and doctors from nine European countries warned in an open letter on Wednesday that they only had up to two weeks’ worth of some medicines used in intensive care units.

However Sanofi is running at 93% capacity according to Hudson, as staff with coronavirus symptoms such as fever and any employee who has been in close contact with them are sent home for two weeks.

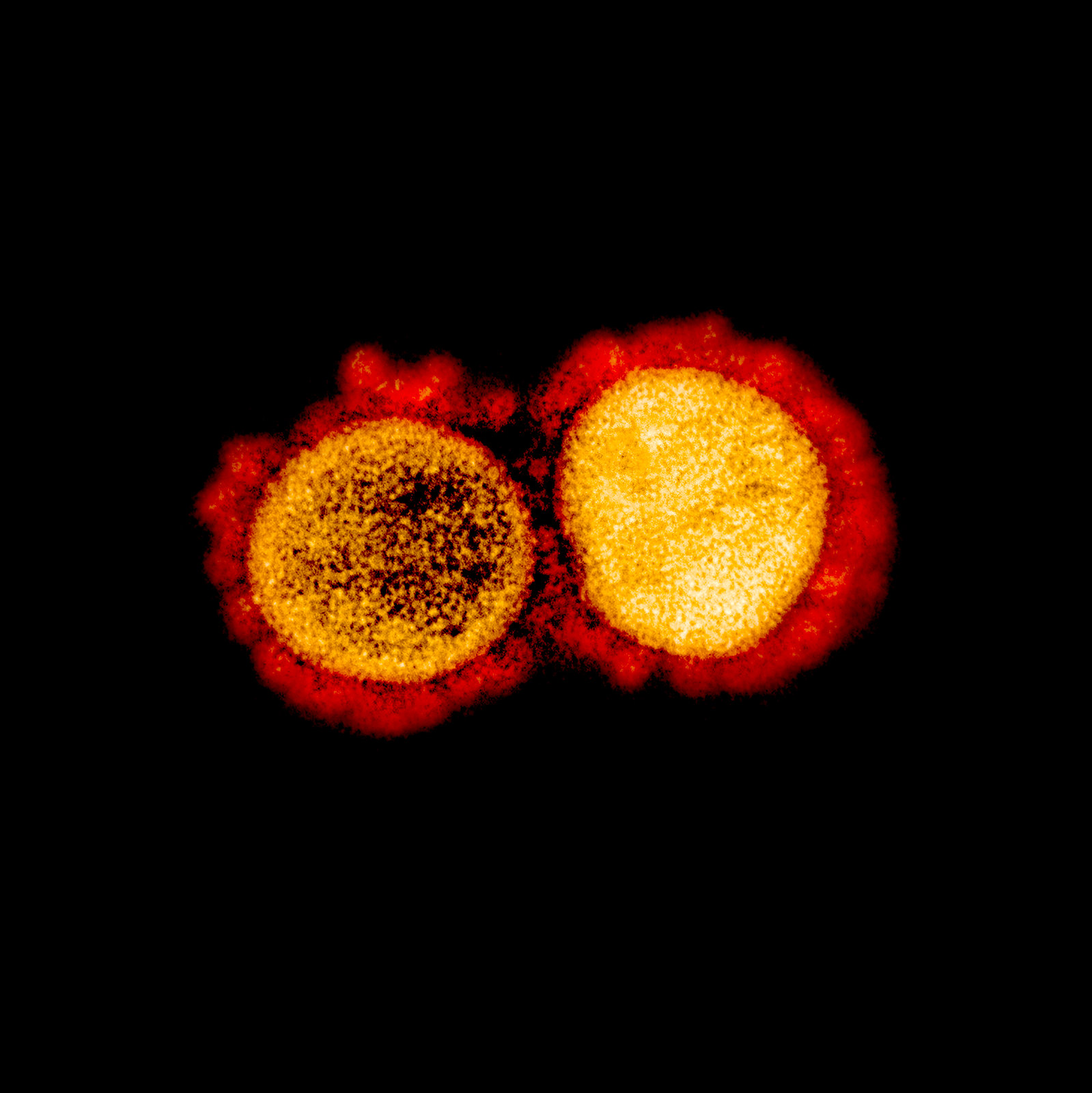

Feature image courtesy of Rocky Mountain Laboratories/NIH