Convalescent plasma misses the mark in phase 2 trial

Hopes that antibody-laden plasma taken from recovered COVID-19 patients could lessen the severity of the disease in others have taken a knock.

The 464-subject PLACID trial – carried out in India – found that the use of so-called convalescent plasma was unable to prevent progression to severe disease or reduce mortality in people hospitalised with moderate COVID-19.

The finding comes after the US issued an Emergency Use Authorisation (EUA) for convalescent plasma in August, despite opposition from some medical experts who said it was premature as the safety and efficacy of the approach had not been established in human testing.

The approval also came amid a spat between the FDA and President Trump, who had accused the agency of impeding progress on coronavirus therapies, and was followed by an embarrassing data gaffe by agency head Stephen Hahn during a press conference announcing the EUA.

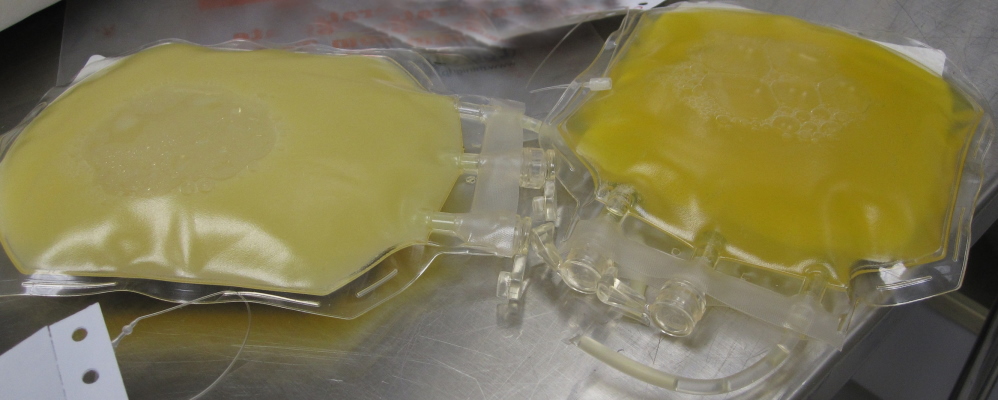

Some countries, including the UK, have been collecting and stockpiling convalescent plasma in the hope that it can be deployed quickly to patients if it proves effective in clinical trials.

Now however, it looks like those who advised caution may have had good cause. While it’s worth pointing out that PLACID was an open-label rather than a double-blind study, the trial investigators claim it “approximates convalescent plasma use in real-life settings".

Studies have shown convalescent plasma from COVID-19 survivors contains antibodies with potent antiviral activity, but there are a lot of unanswered questions about use in patients, including the levels of antibodies needed to be effective, the timing of plasma donation and treatment and the types of patents most likely to respond.

Writing in the British Medical Journal, the authors – led by Anup Agarwal of the Indian Council of Medical Research in New Delhi – say that while prior studies have suggested that convalescent plasma can reduce viral load, the time patients need to spend in hospital, and death rates, that wasn’t the case in their trial.

The primary outcome – progression to severe disease or all-cause mortality at 28 days – was seen in 19% of patients receiving plasma plus standard supportive care, compared to 18% of those in the control arm on supportive care alone.

There were some beneficial effects, including shorter times to resolution of symptoms like shortness of breath and fatigue, but plasma therapy didn’t seem to improve biomarkers for the runaway inflammation that is associated with COVID-19 requiring hospitalisation.

In an editorial accompanying the study, Elizabeth Pathak of the Women's Institute for Independent Social Enquiry in Maryland, US, said that as the study wasn’t blinded, it was possible that patients who knew they were getting plasma might expect to feel better, and so reported improvements in symptoms.

She also points out that convalescent plasma isn’t without risks – in fact, the FDA specifically warns about the risks of blood clots with the therapy, particularly in older patients and those with cardiovascular risk factors.

https://twitter.com/califf001/status/1320414538370568193

Other studies of convalescent plasma are still ongoing, including the UK RECOVERY trial which has already shown the benefits of the steroid dexamethasone in adults with COVID-19, as well as the failure of the antiviral combination lopinavir-ritonavir.

Convalescent plasma is one of three other therapies being put through their places in the study.