Time to ask companies why they don’t submit to NICE?

Companies can choose whether or not to submit to NICE to have their products appraised. Many do, presumably because they want market access in the UK and there are likely to be positive ripples from getting a NICE seal of approval with other payers around the world. But some companies choose not to.

Leela Barham looks at what has been happening to the number of non-submissions at NICE, updating on trends last looked at in 2020. With more companies choosing not to submit to NICE, is it time to ask the industry why that is?

Industry asked for more NICE appraisals

The 2019 Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS) introduced a new commitment that England’s HTA body, NICE, would be appraising all-new active substances (NAS) in their first indication as well as extensions to their marketing authorisations to add a significant new therapeutic indication unless there was a clear rationale not to.

That implies that industry – as represented by the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) who negotiated the deal with the UK government – sees value in NICE appraising drugs. Funding follows a positive NICE technology appraisal recommendation. But it seems that for some companies at least, it’s better to forgo an appraisal.

A rising trend in non-submissions

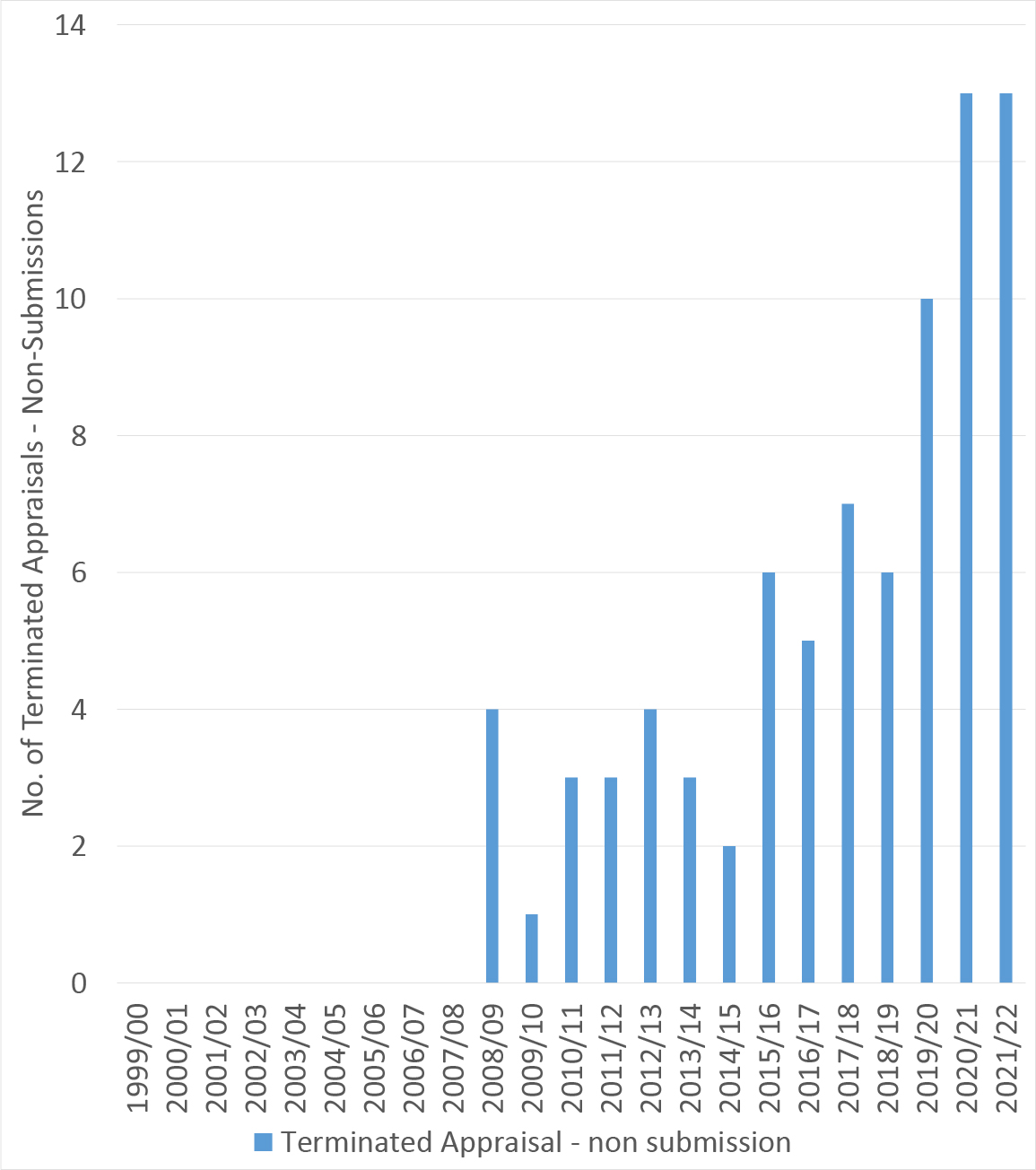

Looking back over time it’s clear that non-submissions have been rising. An all-time high of 13 non-submissions was seen in 2020/21 and the same number of non-submissions was also seen up to November 2021, with four months left to the financial year (Figure 1).

All of these non-submissions are for pharmaceuticals. According to NICE’s integrated performance report tabled for the January 2022 board meeting, NICE had expected 10 non-submissions for the full 2021/22 financial, below the 13 already seen.

Figure 1: Trend in number of non-submissions, 1999/00 to 2021/22

Source: Analysis of NICE data. Note: most recent appraisal included in the NICE data was published on 17 November 2021.

Total non-submissions has hit 80, with recommendations for terminated appraisals translating to 7 per cent of all of NICE’s recommendations made or 8 per cent of all of NICE’s recommendations for pharmaceuticals.

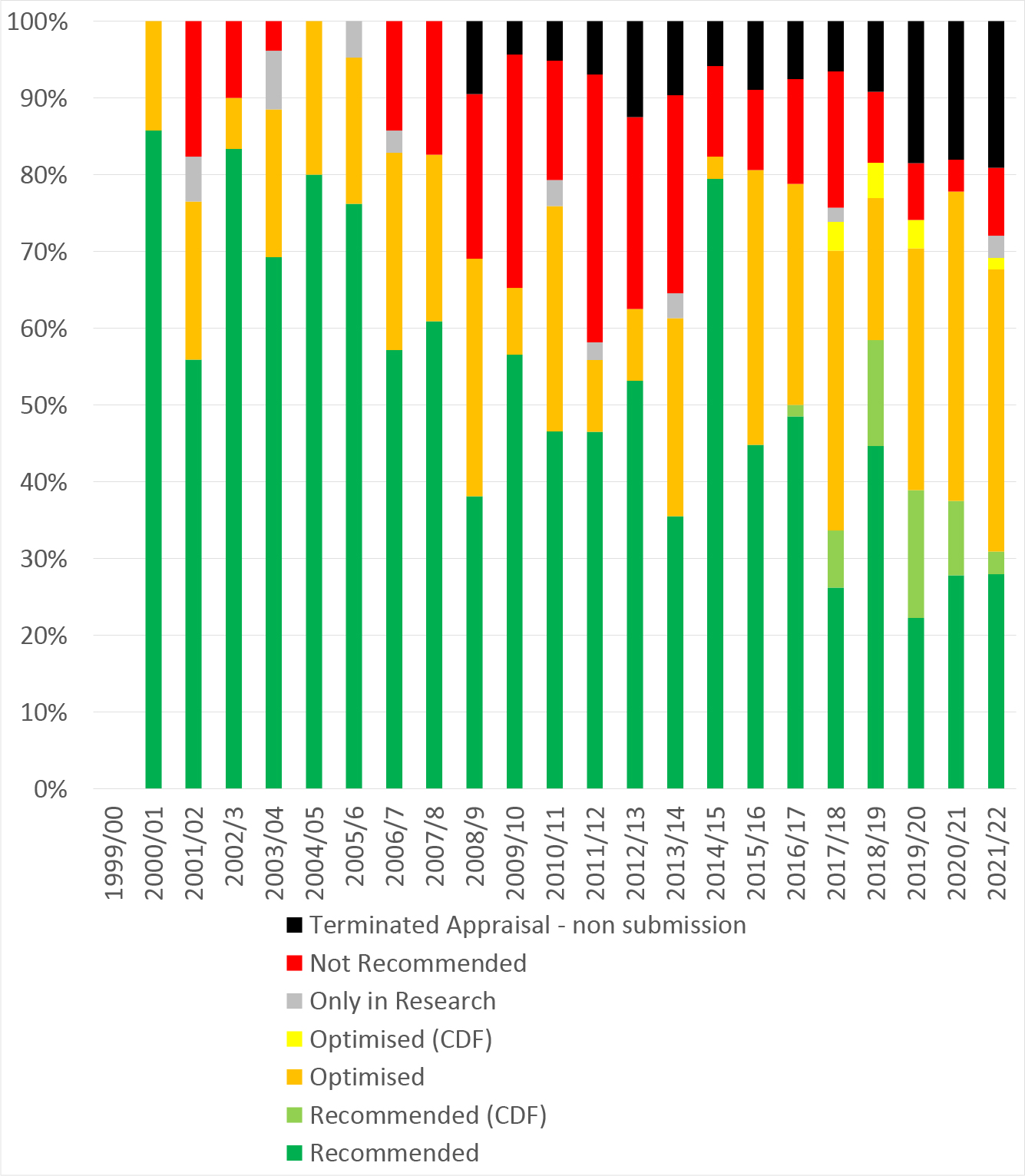

The more worrying stats come as non-submissions are considered overtime. In 2015/16 (the year before the Brexit referendum) non-submissions accounted for 9 per cent of all recommendations made that year. By 2020/21, the most recent fiscal year that has complete data, it’s 18 per cent (Figure 2).

Figure 2: NICE recommendations, 1999/00 to 2021/22

Source: Analysis of NICE data. Note: most recent appraisal included in the NICE data was published on 17 November 2021.

Double-edged sword

For NICE at least, the non-submissions are a double-edged sword. On the one hand, there’s less work to do. That’s welcome for an agency that has been flagging capacity constraints.

Yet since companies pay for technology appraisals, it’s less welcome as it directly impacts income for the agency. Expenditure on appraisals, including highly specialised technologies, from April 2020 up to October 2021 was £7,562,000 but income was £5,782,000. That left a gap of £1,744,000.

Reasons not to submit

The obvious question to pose is why are companies choosing not to submit? There could be many reasons.

The UK is just one market for companies to launch in. Traditionally the UK has been an early launch country, but there have been questions about whether this has been affected by the decision to leave the European Union (EU). There are probably as many who say that Brexit has made the UK less attractive as those who say the opposite.

Brexit may not be the only possible explanation. Similar to Brexit, some have talked up government policies, such as the Life Sciences Vision, and see these as encouraging industry to launch in the UK. Some say that the reality is that it’s just talking and there are still – despite many efforts to address the problem - issues of access which mean that the UK is no longer a priority launch country.

NICE is seen as a world leader in HTA yet there are plenty who can find fault with their approaches. Changes are on the cards, a greater willingness to draw on real-world evidence as just one example, from February 2022 onwards. These are the result of NICE’s more than three-year review of methods and processes that were published in January 2022. These changes may not be enough for those who believe NICE isn’t fit for purpose. Why submit if you believe that NICE is going to say no?

Out of scope of NICE’s review was the main cost-effectiveness threshold that NICE uses of between £20,000 to £30,000 cost per Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY). That means that even with some changes in the evidence and methods that might be possible to put into a company submission to NICE, it may still be tough to hit the value for money bar that NICE uses.

Not being able to hit the cost-effectiveness threshold can be an issue for follow on indications even if earlier indications have been approved by NICE. If a lower price would be needed to secure NICE approval in a follow-on indication that price would apply to all earlier indications. This is, in essence, a lack of pricing flexibility that is not aligned with the way that NICE looks at value by indication. Price can typically only be by brand, although some different prices can come through confidential agreements reached through special funds like the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF). The problem is that a lower price for all indications may not be commercially palatable, and mean companies put forward some, but not all, indications for NICE scrutiny.

Arguably minor in the grand scheme of things but having to pay a charge for NICE to appraise a new medicine could put off some companies. The charge for a Single Technology Appraisal (STA) – the approach most often used by NICE - is £142,800 for 2022/23, although a lower charge applies to small companies. That hardly seems much but it’s the tip of the iceberg for the cost a company pays to submit to NICE, both in terms of in-house time and resources used but often the costs of support from external agencies. If the company doesn’t think it would get a positive anyway, the cost of being NICE’d is another reason not to submit.

Which of these, if any, are the key drivers for decisions not to submit, will be known only by the companies involved. Other companies who have not taken the decision not to submit to NICE could be thinking about it.

Time to ask industry?

Leaving aside what non-submissions mean for patients and the NHS, it is clear that non-submissions are posing an issue for NICE that they need to manage. With non-submissions on the rise, shouldn’t the industry be asked why?

Read the latest article where we answer why companies don't submit to NICE.

About the author

Leela Barham is a researcher and writer who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally, on the economics of the pharmaceutical industry. Leela worked as an advisor to the Department of Health and Social Care on the 2019 Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS).

Leela Barham is a researcher and writer who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally, on the economics of the pharmaceutical industry. Leela worked as an advisor to the Department of Health and Social Care on the 2019 Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS).