What’s affordable anyway? The future of NHS drug spending

The single biggest monetary difference that can be made to the successor to the UK’s 2019 Voluntary Scheme for branded medicines pricing and access (VPAS) is to address the question of how the allowable growth rate for branded medicines is set. Now that VPAS has hit the mid-point and stakeholders are already thinking ahead to the next deal, Leela Barham delves further.

The UK’s 2019 VPAS is a successor to the 2014 Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS). That in turn was the successor to several PPRS (some had slightly different names) that date all the way back to 1957. The current deal will end on the 31 December 2023; meaning the scheme has just hit its mid-way point. With negotiations on schemes typically starting 18 months or so before the end of the current one, it’s likely that many will already be thinking about what comes next.

The big change that has occurred over all these years has been the nature of the scheme; whilst profit control is still part of it, the crux of the deal now rests on keeping the branded drugs bill ‘affordable’. Instead of price cuts and the desire to keep profit margins within reasonable bounds, the scheme rests on members of the scheme making paybacks to the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) if an allowable growth rate on NHS spend on branded medicines is exceeded.

The 2019 VPAS, like the 2014 PPRS, has essentially set a cap on spend on branded medicines and it’s the member companies that pays any amount above that cap. The cap goes one way: the NHS will never spend more but the industry is not guaranteed that it will spend as much as the allowable growth rate implies. In practice though, payments have been triggered. Why? Because the spend on branded medicines has always gone above the allowable growth rate.

Assuming that radical change is off the cards – it always felt that once a cap had been introduced it would be hard to remove and the continuation of it from the 2014 deal to the current one seems to back this up – the biggest money issue on the table for the next deal is just what the allowable growth should be.

Affordability and allowable growth

Affordability is a real issue, perhaps even more so in these COVID-19 times. The NHS in England, for example, saw a boost to its budget to reach £212 billion in 2020/21 to help cope with COVID-19 but there are concerns voiced that the budget for 2021/22 of £181.4 billion is just not going to be enough to keep up with the care that people need. It makes sense to try to squeeze as much out of what is available as possible.

This broader financial picture shapes the desire for the DHSC – and NHS England and NHS Improvement (NHSE&I) who were involved in negotiating the 2019 VPAS – to keep branded medicines spending in check. Whilst it won’t be the true spend – because of VPAS rebates plus other discounts in the supply chain – NHS Digital’s November 2020 release of prescribing costs in hospitals and the community 2019/20 put spend on medicines in England at £20.9billion.

Yet the real difficulty comes in when thinking about just what is affordable when it comes to branded medicines. The 2019 VPAS has set an allowable growth rate of 2%, anything above that triggers payments. And those payments add up, with £843 million paid during 2019 and £432 million according to the latest figures from DHSC published in February 2021. It’s also true that the baseline spend wasn’t adjusted between schemes, essentially baking in a smaller market size overall.

The 2019 VPAS doesn’t explain the choice of 2%. It’s slightly more than the growth rates that were included in the 2014 PPRS (0% in 2014, 2015, 1.8% in 2016, 2017 and 1.9% in 2018), but those also didn’t have a clear underpinning set out in the published deal either.

So how can we tell if 2% is the right or wrong number? There are different ways of looking at this.

Keeping pace with growth in NHS funding?

One way of thinking about affordability of branded medicines is in terms of whether the growth in spend is keeping pace or exceeding the growth in the budget for the NHS. The 2% allowable growth rate puts spending on branded medicines at more than the average of 1.4% growth in the NHS budget for England seen from 2010/11 to 2018/19. Yet it would be far below the 3.7% that the NHS has seen, on average, over the last 70 years.

This would point to any future scheme allowing for a higher growth rate in branded medicines spend, if for no other reason than consistency with investment in the NHS as a whole. A sort of fair's fair approach. It could – although this depends upon how the growth in the NHS budget overall is determined – bring in a clearer link to need. This assumes that there is a relationship between spending on the NHS and health care needs which to a degree there is likely to be, but perhaps not a one-to-one basis.

Keeping pace with growth in the UK economy?

Since the NHS is funded by taxation, another way to think about affordability would be the growth of the economy. When the economy is growing, Ministers could put more into the NHS – including medicines – and vice versa. This option would make the link clearer between the economy and pharmaceutical spend than linking to NHS spend as a sort of intermediate step. Perhaps that has some appeal from an industrial policy perspective as it would recognise that life sciences brings benefits aside from those related directly to health.

Yet it’s difficult in these COVID-19 times to really know how the UK economy is faring; government interventions in the form of furlough payments are ongoing (at the time of writing) and whilst the UK has re-opened the economy to a degree, it’s not yet reached what will likely be the new normal. Predictions from the Bank of England suggest that whilst growth in the economy for the UK in the near term looks good, it may only just get the UK back to where it was in 2019.

It’s difficult to draw a conclusion on whether it’s a good idea, or not, to more formally set an allowable growth rate for branded medicines that relates to the growth in the wider economy. In the specific case of the current VPAS, if that had been the case, it would have had far reaching consequences as no-one foresaw the pandemic which led to an annual growth rate of -9.9% in the UK’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2020. There are also other indices that might be used; growth rates in prices in other industries have often had a measure of inflation used in their calculation.

Unlike spending on the NHS, which saw a COVID-19 boost but will return to more modest growth, the growth in the economy may be more volatile. In turn, it’s also going to be less predictable and pose challenges for forecasts that are used to negotiate on the scheme, but also inform the mechanics such as setting the payment percentage of sales that each member company needs to pay to ensure the overall target on allowable growth is met.

Keeping up with the Jones?

Those who remember the Blair era will remember that there was a goal for the UK to increase funding to the EU average spending on health care as a proportion of GDP. Comparisons with other countries are often made when it comes to spending on medicines too; the ABPI did this a while back.

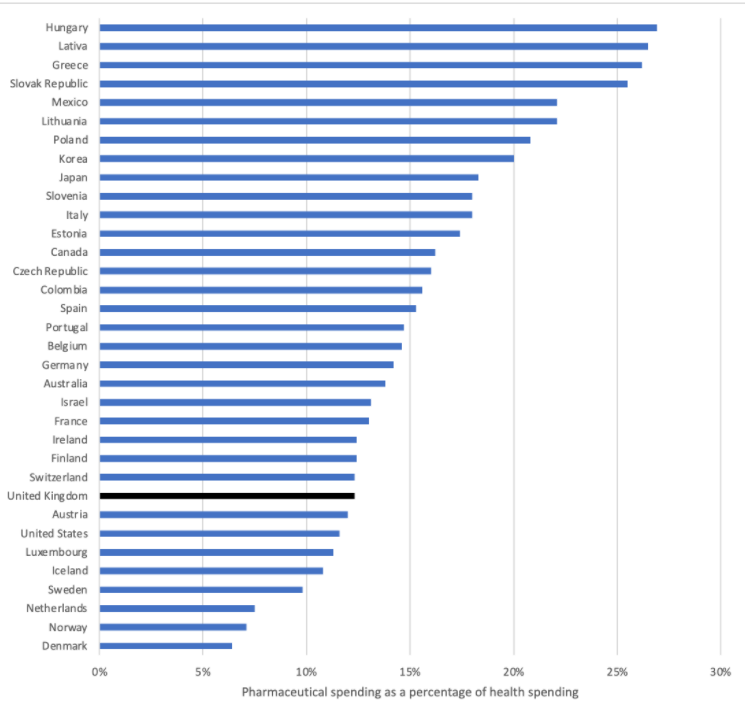

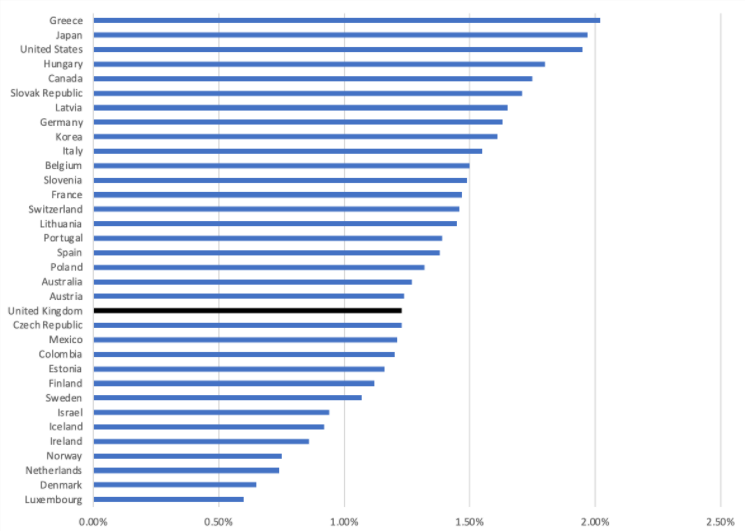

Based on the latest OECD data the UK is low in the OECD countries league table, be that for pharmaceutical spend as a share of total health expenditure or GDP (figure 1 and figure 2 respectively).

Figure 1: Pharmaceutical spend as a percentage of total health expenditure.

Source: OECD (2021), Pharmaceutical spending (indicator). doi: 10.1787/998febf6-en (Accessed on 09 June 2021). Note 2019 data or latest available.

Figure 2: Pharmaceutical spend as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product

Source: OECD (2021), Pharmaceutical spending (indicator). doi: 10.1787/998febf6-en (Accessed on 09 June 2021). Note 2019 data or latest available.

If allowable growth was set at a rate to try to keep up with other most other countries it would, in effect, no longer be binding as most spend more than the UK does as a share of total expenditure on health or GDP. That would make it unattractive to government so is presumably a non-runner. But it is a valuable question to be posing; who has got the level of investment in medicines right, those who spend less, or those who spend more?

Spending wisely should be the goal

It’s worth stepping back too and remembering that branded medicines are a relatively small share of NHS spend; after rebates Ministerial figures put it at around 12-13% and that was consistently the case from 2010/11 to 2015/16. OECD data for the UK for 2018 puts it at 12.3%.

The various interventions in the market-place – and there are many, prices are influenced by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and their cost-effectiveness threshold, deals struck with NHS England and NHS Improvement (NHSE&I), tendering etc – have achieved a stability in the share of NHS funds spent on medicines over time. Supply side factors will have played a role too: competition and generic use.

It may also not be wise to focus on keeping a fixed share; in some cases, it might be advantageous to spend more on medicines to save elsewhere, or vice versa. And you only know this when you get down to a more granular level and that’s exactly why NICE does their work; to look at whether adopting a new treatment offers value at the margin. Perhaps it’s this that explains how the UK has come to the pragmatic approach of having both a limit on overall spend but still retained the role of an agency like NICE to help direct resources to be best value medicines within that. Arguments to suggest that NICE is no longer needed have never held much sway.

The next deal, if it retains a capped approach, will need to have an allowable growth rate. What remains to be seen is whether this growth rate can be based on an objective measure or, perhaps more likely, emerge from the smoke and mirrors of the negotiation.

About the author

Leela Barham is researcher and writer who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally, on the economics of the pharmaceutical industry. Leela worked as an advisor to the Department of Health and Social Care on the 2019 Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS).