Successful brand building means solving customer problems

Pharma marketers need to listen to HCPs and patients to find out what issues they face and then position products to meet these needs.

In a recent presentation Michael Holgate, founding director of Brand Genetics, talked about the first rule of successful brand building being: "No problem, No opportunity". He told the audience, "We have to wait until our customer's mind is open before they are willing to buy." He was giving an audience of pharmaceutical marketers a perspective on what constitutes successful consumer brand building.

In pharmaceutical marketing we can go further and state "No problem, No brand".

The days when share of voice and representative power could create a need for a specific brand attribute are long gone. Yet how much of our market research budget do we spend researching customers' problems and how much working out how to sell the perceived product's USP (Unique Selling Proposition)? Usually much more is spent on the latter.

While the USP concept was developed in the mid-20th century and may have different titles (Key Sell Point, Key Differentiating Message, Brand Essence etc), the intent is still the same: to line up the competition and focus on the differentiator of our brand.

Let's examine the brand development process in a top-20 pharmaceutical company – a process which is also quite common across the industry. The clinical development team works mainly in isolation from the commercial team, increasingly so because of compliance issues (Sunshine Act et al), until the product hits a phase III gateway. The initial focus of the commercial team is to understand the product, the competitive set and make some initial product forecasts. This usually includes making some assumptions about primary patient segments and conducting some market landscaping and trade-off research.

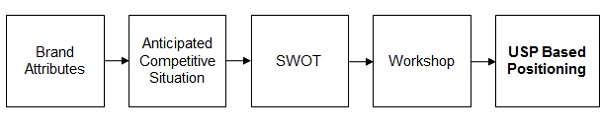

The team also creates a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) and other analyses to synthesise the product's relative advantages and disadvantages versus the competitors. The SWOT then becomes a primary document for an internal positioning workshop and development of the USP (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Common Process

This approach can leave out an important ingredient: a deep understanding of what problem the brand is solving for the customer – the HCP or patient.

"As brand builders, we are interested in the important goals that HCPs are unable to achieve"

The fundamental rule in defining the problems brands solve for the HCP is to use a common language. We often use the term 'unmet need', but this does not translate as a question to ask HCPs, as those who are patient empathetic give a different perspective to those who are not on the unmet patient needs. All clinicians, however, translate patient unmet needs into goals for themselves, whether they are patient empathetic or not. Consequently, more robust data is collected when asking HCPs about their goals. As brand builders, we are interested in the important goals that they are unable to achieve with their current product arsenal. This defines the problems that our new product can target.

Of course these problems can change for different patients and where there are common problems (unachieved goals) across groups of patients, we refer to these as Goal States. In the past it was felt that there was just one unmet need that the brand was targeting. Goal States analysis understands that the doctor's goals change in different situations and helps in both competitive and portfolio positioning.

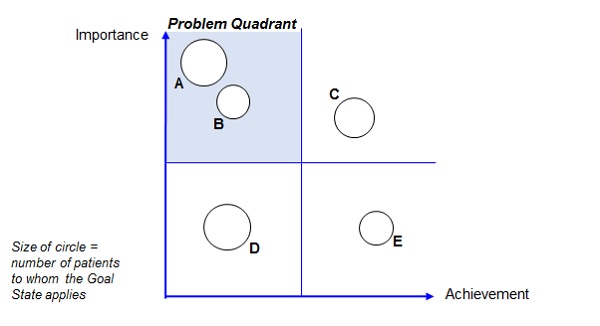

To create a good Goal States map (Figure 2), first it is essential to understand the different patient groups through the eyes of the clinician.

The map guides us straight to the greatest opportunities, in the top-left-hand High Importance/Low Achievement or Problem Quadrant.

Figure 2. Goal States Mapping

Goal State A is the most attractive to target, being both important and not achieved using current products.

For the second target goal, we would discuss the cost implications of increasing the importance of Goal State D versus targeting the smaller Goal State B.

Goal State E is not important and, unless we can provide a significant leap in the achievement of Goal State C, it will not motivate customers. Satisfying Goal State C is cost of entry rather than differentiating.

From this model we know that to build a strong brand there are a number of Goal States that we can target, but achieving Goal State A offers the greatest potential.

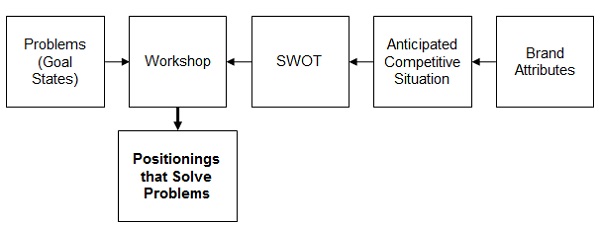

We can now bring this insight on customer problems (unachieved goals) into the positioning process to create the recommended process (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Recommended Process

The recommended process does not take any longer than the common process, as market research into Goal States can be conducted in parallel with clinical development.

Indeed, it is better to conduct Goal States research before phase III trials begin as it will inform both how to define the patients (so that they match the way HCPs see them) and, more importantly, secondary endpoints that will solve HCP problems.

Thus we can avoid wasting time with USP positioning that does not solve customer problems and focus on positioning, and clinical data points if we are early enough, that solves the main customer problems.

In one case history we used the Goal States approach for the European launch of a once-a-day version of a twice-a-day product in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. We were able to show that compliance was a much less important and more satisfied Goal State than nocturia (night time toilet visits). So the problem the brand needed to solve for the customer and patient was that of nocturia, rather than compliance. These data were available sufficiently early to position the product on nocturia.

"This was not only successful as a launch but also maintained 60 per cent of its sales after a generic competitor entered the market"

This was not only successful as a launch but also maintained 60 per cent of its sales after a generic competitor entered the market – something that could not have been achieved with a compliance-based positioning.

Another advantage is that if we are solving a problem for our customers then the strength of data they require can be lower. For example, in the above case, secondary endpoint data against placebo was sufficient to successfully support a credible brand story.

Markets are becoming increasingly competitive, as can be seen in the PD1 and PCSK9 arena. In this environment it is even more important that brand positioning development is based on the customer problem being king.

About the author:

Kim Hughes is CEO of THE PLANNING SHOP international. He gained a dual Economics and Business Studies degree and his early career was in consumer marketing at Beecham.

He worked as a strategic brand planner with Bates Advertising London before becoming strategic planning director for the Fortune group of advertising agencies in Australia (Dancer Fitzgerald Sample, the Weston Company, Schofield Sherban Baker and Hammond Advertising).

On returning to the UK in 1987 Kim established THE PLANNING SHOP international with Tina Berry, another strategic planner. He pioneered the company's healthcare division and eventually bought it out and established it as a separate company.

Contact him on +44 (0)20 8231 6888 or at kim.hughes@planningshopintl.com

Read more:

Unmasking the real benefits of online and mobile communities