Redefining the Blockbuster Model: Why the $1 billion entry point is no longer sufficient - part 2

Sarah Rickwood

IMS Management Consulting

In part two of this two-part article, Sarah Rickwood continues to address why the $1 billion entry point should no longer be the benchmark for a blockbuster drug.

(Continued from Redefining the Blockbuster Model: Why the $1 billion entry point is no longer sufficient - part 1)

Market share

An effective approach is defining blockbuster products in terms of a fixed share of the value of the global pharmaceutical market concentrated into the sales of a single pharmaceutical product.

In 1987, a global sales value of $1 billion equated to 0.74% of the global market’s value. If 0.74% of global market value were still the benchmark for a blockbuster in 2011, sales of $6.3 billion would be needed to meet it – meaning only nine products would be classified as blockbusters: Lipitpor, Plavix, Seretide, Nexium, Seroquel®, Crestor, Enbrel®, Remicade®, and Humira®.

,

"Products with much smaller patient populations are now starting to achieve billion dollar blockbuster status..."

,

If we move to a more recent period, the year 2000, $1 billion in global sales equates to a value share of 0.1% of the global market. By applying the 0.3% market share as the new benchmark, we’d have 43 blockbuster products in the most recent full year.

Moving from the simple hurdle of $1 billion in sales to minimum market share hurdles, a surprising consistency emerges where the pharmaceutical industry has become no better at producing these very large products in the last decade, but equally no worse, as the number of blockbusters defined by market share methods is pretty much the same from 2000 to 2011. This static state of affairs will most likely move to declining numbers in the next decade, as genericisation of existing leading blockbusters, combined with the fragmentation of available potential product markets, will lead to the innovative industry relying on a larger number of products with smaller market shares.

Chained dollars

Another effective approach is the chain dollar approach, which constantly adjusts the value of $1 billion to account for inflation from 1987 to today. This helps determine how much of blockbuster growth is actually monetary inflation. Through the chaining dollar, it is clear that the blockbuster benchmark needs to be adjusted. $1 billion from 1987 equates $1.75 billion in 2011, while $1 billion in 2000 equates to $1.27 billion in 2011.

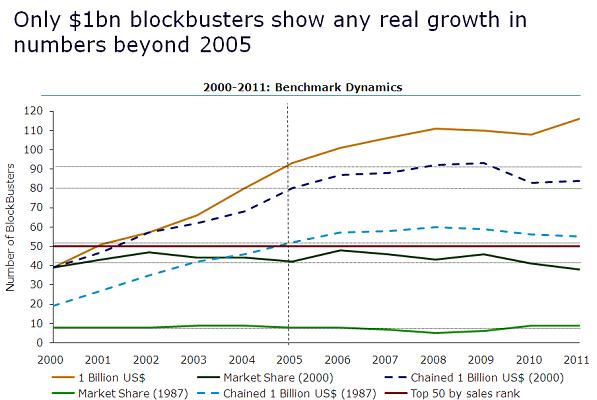

As Figure 1 illustrates, in 2011, there were 116 traditionally-defined blockbuster drugs. However, when sales of these medicines are chained to the value of $1 billion in 2000, the number of blockbuster drugs falls to 84. Further, when 2011 sales figures are chained to the value of $1 billion in 1987, the number of blockbuster drugs falls to just 55.

Clearly, by either measure, market share or chained dollar, there is a substantial group of $1 billion plus products today that have no right to be termed blockbusters.

Figure 1: Only traditionally defined blockbusters show real growth in numbers between 2005 and 2011

Source: IMS Health, MIDAS

A geographic shift

The U.S., the world’s largest pharmaceutical market, has been the cradle of blockbusters due to its size, free pricing and enthusiastic uptake of innovative new products. Regardless of the new benchmark selected, this is changing, as U.S. market share has declined. Proportionately, sales in the top five European markets (U.K, Italy, France, Spain and Germany) have risen. Meanwhile, the pharmerging markets (China, Brazil, Russia, India, Venezuela, Poland, Argentina, Turkey, Mexico, Vietnam, S. Africa, Thailand, Indonesia, Romania, Egypt, Pakistan and Ukraine), despite contributing 44% of all the global market’s value growth in the last five years and being forecast to contribute 60% in the next five, are still not pulling their weight regarding blockbuster sales. While still predominantly denizens of the mature markets, blockbusters need to be driven more by the markets that are driving overall value growth of the world market.

,

"Real growth has happened in the very large ($5-9.99 billion), mid-sized ($2-4.99 billion) and small ($1-1.99 billion) products..."

,

Companies must change

The modern pharmaceutical industry has been shaped by its blockbusters. During the 1990s, companies focused their research on products that would be used by the largest possible patient population. As a result, traditionally-defined blockbusters drove the arms race for vast sales forces, and a share of voice driven commercial model. But, blockbusters are changing, and as they change, so will the companies that depend on them.

We believe that companies that continue to focus on innovation will see a rising dependence on a larger number of smaller blockbuster products, which are more likely to be specialist products and focused on defined patient segments. Changing blockbuster emphasis will be accompanied by fundamental changes in the way companies set expectations, as well as research, develop and commercialize products. We believe that this will strongly impact research-based pharmaceutical companies through resource allocation, patient segmentation, and performance expectations and risk.

The blockbuster model is not dead – even with the re-definition proposed by us. There are still a number of very significant products, and the numbers, if not rising, are not yet in decline. However, it is clear that the blockbuster is changing. With this change, the nature of the world’s largest companies will also change as well.

About the author:

Sarah Rickwood has 20 years’ experience as a consultant to the pharmaceutical industry, having worked in Accenture’s pharmaceutical strategy practice prior to joining IMS Management Consulting. She has an extremely wide experience of international pharmaceutical industry issues, having worked most of the world’s leading pharmaceutical companies on issues in the US, Europe, Japan, and leading emerging markets.

In her time in IMS, Sarah has played a key role in developing the Launch Excellence Thought Leadership and IMS’s Launch Excellence thought leadership studies and Launch Readiness offerings which provide IMS pharmaceutical clients with comprehensive and critical guidance during the crucial pre-launch and launch periods for their key brands. In this capacity she has advised companies on the launch of current and potential blockbusters in many therapy areas and countries.

As the Director of Thought Leadership for the European Business Units, Sarah has managed a highly productive team delivering over 100 client presentations a year, and developing new Thought Leadership on launch, biosimilars, commercial analytics, healthcare system changes, blockbusters, the top 10 company of the future and uptake and access of innovative medicines.

Sarah holds a degree in biochemistry from Oxford University.

Should we redefine the pharma blockbuster model?