Managed Access Programmes: maintaining treatment access post-trial

Managed Access Programmes (MAPs) can cost-effectively meet patient access obligations and release internal resources, says Nicky Wisener.

Many people in the pharmaceutical industry will be familiar with the term Managed Access Programmes (MAPs) but probably only in the 'compassionate use' setting. This is where a doctor is making a special request for a particular medicine – to be used in a pre-approval setting – for an individual patient who has run out of options among licensed drugs.

MAPs can also be used in a range of other circumstances, including when companies are managing the transition of patients exiting a clinical trial and wish to ensure that those who benefitted from the study drug maintain ongoing ethical access until it is approved and commercially available in their country. However, most companies in this situation choose to maintain treatment access with an open-label extension (OLE) trial, despite the fact that a MAP can be a simpler, more cost-effective solution.

Demand for access when a trial ends

When a clinical trial is complete and the sponsor company has the required data available, the company still has an obligation to the patients who took part in the trial.

This is a fundamental principle of all trials in humans. It was first laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964i, an agreement which has been continually updated over the years, and is still a cornerstone of clinical trial regulations around the world.

The Declaration states that clinical trial sponsors, researchers and host country governments should ensure that all participants in clinical trials have post-trial access to treatments identified as beneficial during the trial.

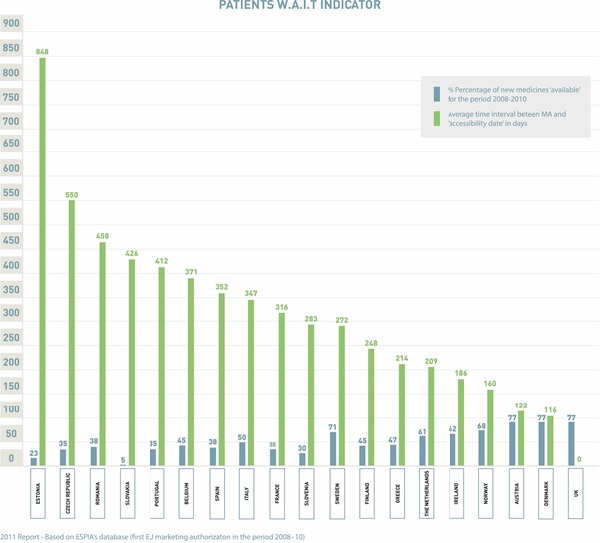

This means trial sponsors have a duty to ensure any such demand is met, which is particularly important when you consider the often substantial lag time that exists between regulatory approval and commercial availability in certain countries. Figure 1 illustrates the typical time (in days) between marketing authorisation and commercial availability in countries throughout Europe.

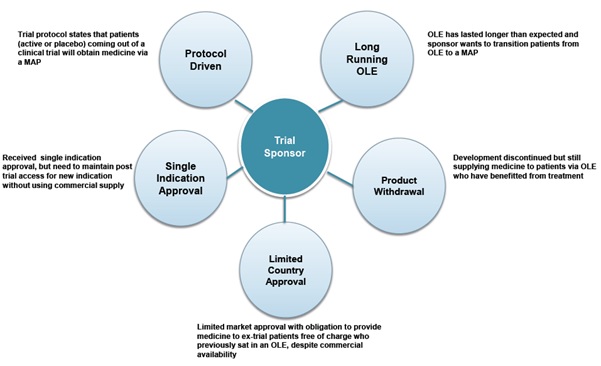

MAP is a term used to encompass a variety of regulatory approaches to providing access to medicines outside the clinical trial or commercial setting. There are several scenarios when sought-after therapies might fall into this category:

• When they are still in clinical development and have yet to be approved

• When they have completed clinical development and ex-trial patients need continued access to medicine, or treatment naive patients have no alternative available

• When they are approved in one country, but not in another

• When they will never be approved in certain countries where patients may still need access.

MAP versus OLE

If a company needs to extend access to trial participants beyond the clinical trial and is doing so primarily for treatment access purposes, not for data collection, then a MAP is a more efficient way of meeting these obligations than the usual OLE route.

"OLE trials are still run very much as clinical trials, bringing with them a considerable administrative and financial burden"

That's because OLE trials are still run very much as clinical trials, bringing with them a considerable administrative and financial burden to a pharmaceutical company.

In contrast, there are fewer resources required to run a MAP across diverse geographies. Such programmes can be outsourced to partners with dedicated expertise in this area, freeing a sponsor company's time and human resources, whilst enabling the company to meet its ethical obligation to patients.

Figure 2. Five ways trial sponsors can use a MAP to manage post-trial treatment access

Why aren't MAPs used more in these situations?

Many pharmaceutical companies have a global clinical development group, which is responsible for conducting clinical trial programmes across all territories.

Once a phase III trial is complete, this group often hands over to the global medical affairs group, which is responsible for taking the drug on to the next stage – regulatory submission – potentially in collaboration with the company's commercial group. The responsibility to take care of ex-trial patients and any ongoing trials generally remains with the clinical teams.

Because the global clinical group is expert in clinical trials, it is natural that its solution to meeting the continued access obligation is to use an OLE. That is what clinical development groups know best; they have systems in place and they're confident about the regulations that govern trials. In contrast, a MAP has different rules and regulations. Clinical teams might not be aware of MAPs as, historically, they have been the domain of the medical affairs group and hence may fall outside their comfort zone. But this should not stand in the way of using the best approach in this situation to meet patient access needs.

Rules governing MAPs in the EU and other jurisdictions

The reality is that, whilst most countries adhere to the spirit of the Declaration of Helsinki, the way that it has been interpreted into regulation is different in each country.

That is equally the case in the European Union (EU), despite its aim to harmonise regulations across the Continent. In reality, because each member state has transposed an EU directive into its own national legal framework, the rules are applied differently in each country.

The regulations surrounding MAPs are often far less stringent than those dictating the processes involved with an OLE trial. However, navigating the local regulatory differences can be daunting. Most pharmaceutical companies are unlikely to have familiarity with, and expertise in, MAPs, particularly if they are being conducted in multiple territories. In these cases, it is often best to partner with a managed access specialist with the expertise to interpret local requirements placed upon physicians, the sponsor company, and the MAP administrator, to ensure access in a fully compliant, timely and cost-effective manner.

"MAPs are an innovative solution for maintaining treatment access post-trial, whilst driving efficiency and reducing overall R&D costs"

Cost implications

From a cost perspective, an OLE trial is significantly more expensive to manage than a MAP, especially considering the extensive site monitoring, data collection and analysis and investigator payment typically involved. These clinical trial components are rarely part of a MAP, because they are not necessary to meet the primary objective of treatment provision.

In addition to the direct cost advantages, the MAP approach can lessen the burden on current resources, so they can stay focused on clinical development activities. MAPs are an innovative solution for maintaining treatment access post-trial, whilst driving efficiency and reducing overall R&D costs.

Medical department leads

Generally, there are two separate groups of individuals within most pharmaceutical companies who could take the lead on reviewing practices in this area: clinical trial leaders at the global level who manage a company's overall clinical strategy, and the regional clinical trial managers who manage the day-to-day demands of trials.

For anyone working in these areas, the message is simple: if you have a number of OLE trials operating purely to maintain access for patients, you should review your strategy, and consider where MAPs might be an alternative.

You might find that you are not deploying internal resources efficiently by using the traditional open-label route and those resources could well be deployed more efficiently elsewhere.

Summary

There are situations in which regulatory authorities may require a clinical trial sponsor to have a system in place to continue to make the drug available to treat study patients after completion of the trial and prior to commercial availability. Independent of a requirement, for ethical and other reasons, many pharmaceutical companies want to ensure that patients completing clinical trials, who are benefiting from treatment, continue to have access to therapy during the period prior to commercialisation.

Extending access for study participants via an OLE trial has been the standard route, but OLEs can have significant costs and require extensive internal resources that a company might prefer to deploy elsewhere. In situations where a company's primary objective is to maintain patient access to treatment a MAP may provide a more appropriate, efficient and cost-effective approach.

Reference

1. WMA Declaration of Helsinki - Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/

About the author:

Nicky Wisener is global business development director at Idis. She joined Idis in 2008 as an account director in the global business development function. Nicky has more than 14 years' experience in the pharmaceutical industry.

She began her pharmaceutical career in the international training department at Zeneca, responsible for the co-ordination of global investigator training programmes within neuroscience. For the next 10 years she worked for Servier Laboratories in a range of sales, marketing, market access and management roles, across disease areas including cardiovascular, CNS and rheumatology.

At Idis, Nicky has worked with a number of top-10 pharma companies and biotechs to educate, support and help design global MAPs. Each programme has unique characteristics and objectives and requires a tailored approach to ensure treatment accessibility to those patients who require it the most.

Nicky holds a BSc in human biology and epidemiology from Liverpool University.

Have your say: To what extent can MAPs replace OLEs?