Exploring the role of pharmacy and self-care in the fight against fatty liver and disease progression

Globally, the incidence of fatty liver disease is increasing at a concerning rate, yet, the solution could be simple.

The associated co-morbidities and prevention pathways are numerous and well known, placing at-scale detection and self-care right at the heart of liver care. It is in this space that pharmacists have a unique and critical role to play in changing the course of this growing burden.

Liver disease in numbers

Today, an estimated 1.5 billion people live with liver disease (a 13% increase since the start of the millennium), leading to 2 million deaths annually. In the USA, of 116,292 liver transplants for chronic liver disease, those due to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) (formerly non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)) increased from 19% in 2013 to 27% in 2022.1

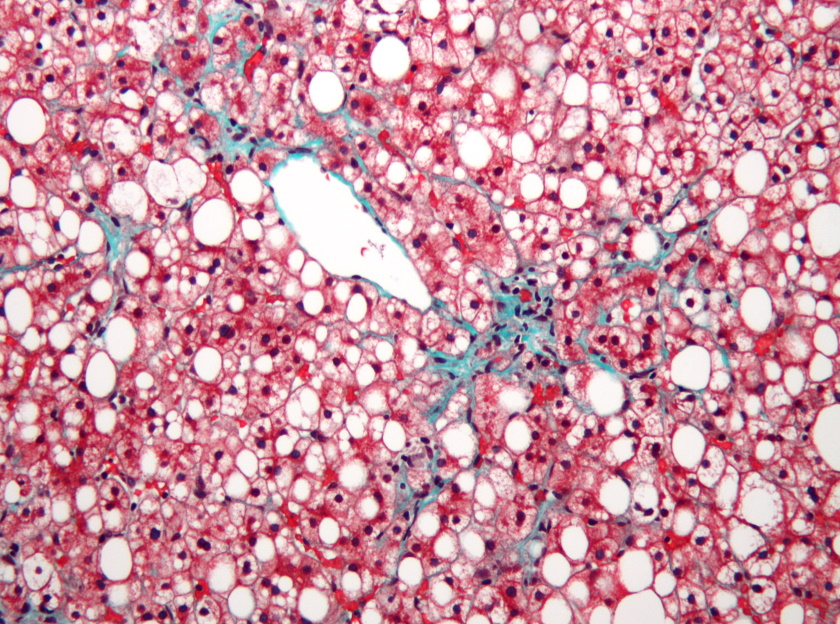

Although over 100 types of liver disease exist, fatty liver disease is one of the leading types. It is also one of the main reasons for patients to go onto a liver transplantation list in the USA. In addition, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is now called MASLD (metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease), due to the frequency of it being associated to the triad of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (CVD).2 These co-morbidities are a common risk indicator for the first stage of liver disease — fatty liver and MASH. For instance, in India, nearly 12% of patients newly diagnosed with chronic liver disease also have diabetes. Likewise, in the Philippines in 2008 it was seen that, of NAFLD patients studied, 69% of those also had diabetes.3

Despite the clear trends, there is a noticeable lack of awareness or focus on the common link between liver disease and these co-morbidities. Liver disease does not receive the necessary attention from governments, policymakers, patients who live with type 2 diabetes or a cardiovascular condition, or most clinicians.

This is a situation that needs to change.

Sharing best practices

The Global Liver Institute (GLI), in partnership with the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), hosted its second annual conference in June: “Together for Better Liver Health: Amplifying Best Practices Globally”. Held on the sidelines of the 77th World Health Assembly in Geneva, Switzerland, the event aimed to convene global leaders and serve as a catalyst for new liver health policy initiatives.

It also provided a platform for the launch of the latest GLI report, ‘Best Practices in Liver Health Policy: A Liver Health is Public Health Report’, which assesses successful liver health approaches to inform and encourage effective policies worldwide. Like the event, this report underscores the ongoing global challenges faced by patients and highlights successful measures from countries including Egypt, India, Ireland, Scotland, and Turkey. These include using primary care data to screen high-risk populations and integrating fatty liver disease into national programmes targeting non-communicable diseases.

The case from Egypt proved especially inspiring. The Egyptian Minister of Health & Population, Dr Khaled Abdel Ghaffar, detailed Egypt's successful efforts to eradicate hepatitis C. He explained how, within 10 years, the country managed to reduce the proportion of the population suffering from hepatitis C from 10-12% to just 0.38%, positioning the country as the first to attain the “gold tier” status on the path to elimination as per World Health Organization criteria.

The steps involved in this successful project (targeting 105 million people) were:

- Understanding the problem through the establishment of baseline data

- Mass screening and surveillance

- Defining a treatment protocol

- Localising treatments (local production) to make them affordable

- Increasing awareness and prevention

- Training healthcare professionals

This was a collaborative effort involving government, healthcare professionals and, crucially, the public. As Dr Ghaffar noted: “You need to have a public awareness of the problem so that you will encourage people to start going through the process of screening, diagnosis, and proper treatment journey”.

Pharmacy as a pathway to prevention and early detection

I was pleased to be part of the discussion panel at this event, exploring a four-tier approach to improving liver health:

- Prioritising public education

- Ensuring accessibility to preventive measures

- Promoting early detection

- Integrating seamlessly with healthcare systems

It was helpful, also, to discuss the role pharmacy could play in this approach, given its prominent public presence and frontline status. Indeed, pharmacists are, with little exception, the most accessible healthcare professionals to the public. They focus on a holistic, individual approach to patient care, balancing medication with conditions, and advising on self-care and what to be vigilant for.

So, for the pharmacy profession, embedding more screening, providing healthcare recommendations for diagnosed individuals, and emphasising the importance of early testing for customers with co-morbidities makes complete sense.

However, there are some barriers to overcome. Conducting evaluations in a pharmacy can be challenging, for example, largely due to low blood biomarker analysis capacity. Nevertheless, with the right tools and innovation — non-invasive portable devices, scientifically validated calculators, and tailored screening questionnaires — this obstacle can be overcome. Some countries, like the Philippines, already use self-assessment tools and questionnaires that encompass key risk factors and biomarkers associated with fatty liver disease. These can be filled out by patients in the pharmacy or at home while, at the same time, increasing patient awareness of fatty liver and encouraging healthy attitudes and behaviours to either prevent or alleviate the condition.

Of course, the specific roles pharmacists can play will depend to a large extent on the health system, resource availability, extent of collaboration, and pharmacy practice in each nation. Take the UK, for instance. The UK's Pharmacy First Service positions pharmacies as the initial point of contact for patients to alleviate pressure on overburdened NHS services. They can currently treat seven health conditions, and adding fatty liver disease to this list could greatly benefit both patients and clinicians.

Again, collaboration is key to the success of this initiative, and with fatty liver there is a clear opportunity for endocrinologists, cardiologists, and general practitioners to act as a pathway to self-care by working with pharmacy to facilitate more liver testing and potential over-the-counter interventions to deter further complications for at risk patients.

Where next?

If we are to reverse the trend in liver disease and improve outcomes for those most at risk, liver health must be given much greater priority at both policy and practice levels. Both are duty-bound to nurture an informed public and drive a shift towards prevention and early treatment, rather than later intervention (which for those with co-morbidities can lead to further complications and greater associated expense).

Pharmacists are uniquely positioned to support this drive. They can provide an opportunity to screen high-risk patients to detect the first stages of fatty liver disease early before referring to more specialist care where necessary. They are trusted to provide reliable information, review all medications simultaneously, and offer reassurance to patients and their families with a safe and professional service. They can also suggest over-the-counter solutions to complete a holistic approach towards improvements in health and provide education and counselling to promote self-care and ownership among individuals, helping to reduce disease progression.

So, whatever role we play as HCPs, let’s do more to champion the liver. By working together to increase patient awareness and improve the pathway for liver health, we can prevent or halt disease progression in the early stages and reduce this growing burden for patients, and healthcare systems.

References

- Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Al Shabeeb R, Eberly KE, Shah D, Nguyen V, Ong J, Henry L, Alqahtani SA. The changing epidemiology of adult liver transplantation in the United States in 2013-2022: The dominance of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and alcohol-associated liver disease. Hepatol Commun. 2023 Dec 22;8(1):e0352. doi: 10.1097/HC9.0000000000000352. PMID: 38126928; PMCID: PMC10749707.

- Tokutsu K, Ito K, Kawazoe S, et al. Clinical characteristics in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in Japan: a case–control study using a 5-year large-scale claims database. BMJ Open 2023;13:e074851. doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2023-074851

- De Lusong MA, Labio E, Daez L, Gloria V. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the Philippines: comparable with other nations? World J Gastroenterol. 2008 Feb 14;14(6):913-7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.913. PMID: 18240349; PMCID: PMC2687059.