WHO criticises lack of big pharma antibiotic R&D

Big pharma still continues to look upon antibiotic resistance as somebody else’s problem, the World Health Organization has warned, in a dismal update outlining the lack of private investment in compounds that target the most dangerous superbugs.

In a review of current clinical development, the WHO echoed the views of many other experts in the field that a lack of private investment is translating into a weak pipeline that offers little improvement over already-marketed compounds.

Two new reports from the WHO showed that most of the 60 products in development – 50 antibiotics and 10 biologics – do not target the most dangerous resistant strains of gram negative bacteria.

The reports Antibacterial agents in clinical development – an analysis of the antibacterial clinical development pipeline and its companion publication, Antibacterial agents in preclinical development also found that research and development for antibiotics is primarily driven by small- or medium-sized enterprises with large pharmaceutical companies continuing to exit the field.

In 2017, the WHO published a priority pathogens list outlining 12 classes of bacteria plus tuberculosis that are posing an increasing risk to human health because they are resistant to most existing treatments.

The independent experts who drew up the list hoped to encourage the medical research company to develop innovative treatments for resistant bacteria.

But since the list was drawn up there has been a steady flow of bad news in terms of antibiotic research – at the end of 2019 Melinta became the latest in a string of specialist biotechs in the field to go bankrupt.

And as the WHO pointed out, larger drugmakers including AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Sanofi have stopped developing antibiotics.

Report authors said: “In the last couple of years, the majority of the large research-based pharmaceutical companies have exited the field of antibiotic R&D. Despite commitments from the private sector through the AMR Industry Alliance, concrete action is limited.”

While 32 of the 50 antibiotics are targeting priority pathogens, the majority have limited benefits compared with existing antibiotics.

Only two target the multi-drug resistant gram-negative bacteria that the WHO is most worried about due to their rapid spread.

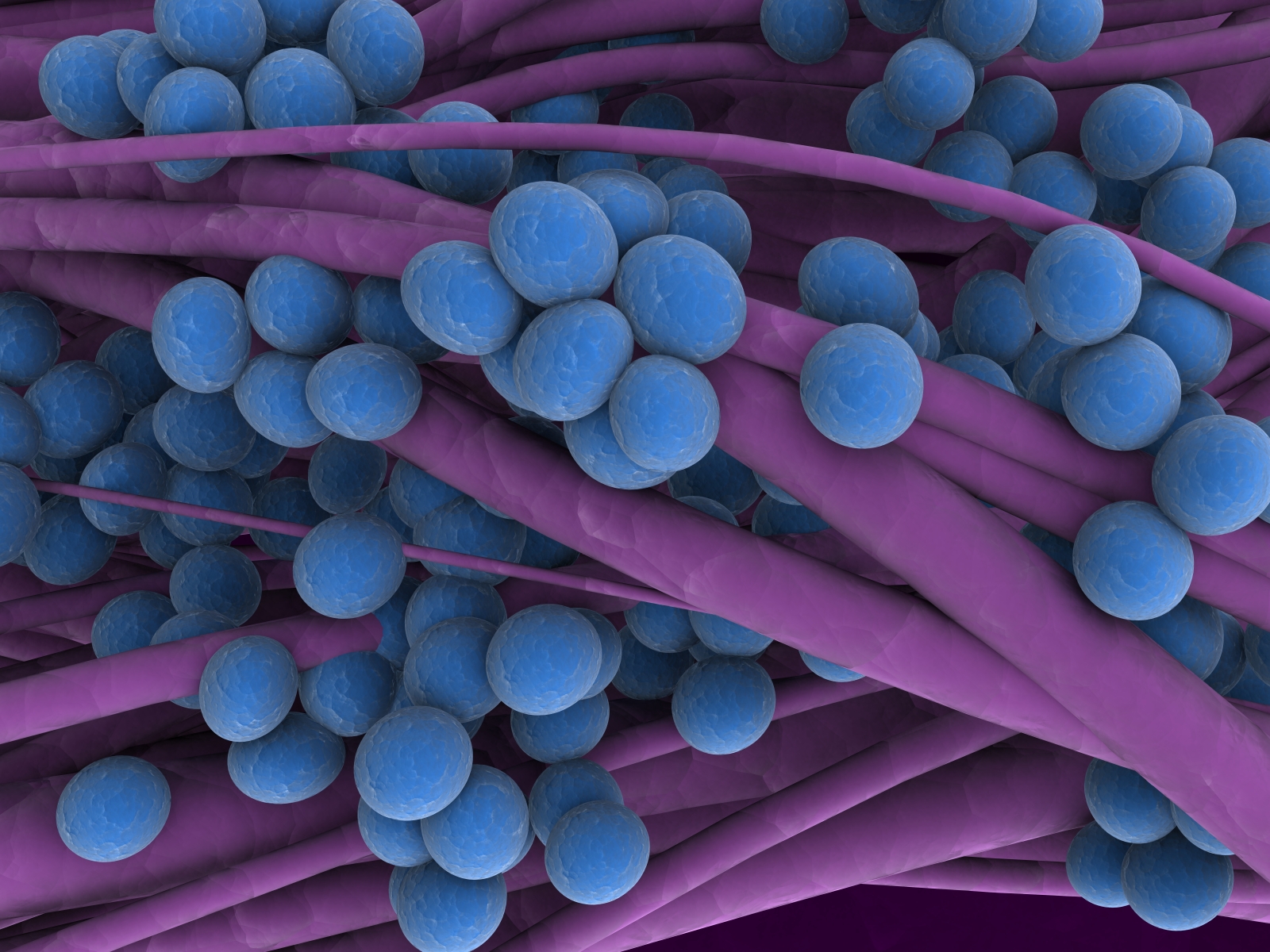

Gram-negative bacteria, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli, can cause severe and often deadly infections that pose a particular threat for people with weak or not yet fully developed immune systems, including newborns, ageing populations, people undergoing surgery and cancer treatment.

The report highlights a “worrying gap” in activity against the highly resistant NDM-1 (New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase 1), with only three antibiotics in the pipeline.

NDM-1 makes bacteria resistant to a broad range of antibiotics, including those from the carbapenem family, which today are the last line of defence against antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections.

On a more positive note, the pipeline for antibacterial agents to treat tuberculosis and the gastro bug Clostridium difficile is more promising, with more than half of the treatments fulfilling all the innovation criteria defined by WHO.

The pre-clinical pipeline shows more innovation and diversity, with 252 agents being developed to treat WHO priority pathogens.

However, these products are in the very early stages of development and still need to be proven effective and safe.

The optimistic scenario is for the first two to five products to become available in about 10 years, the WHO said.

Pointing out that new treatments alone will not solve the crisis, the WHO has its hopes pinned on the not-for-profit organisation the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP), which it helped to found.

GARDP hopes to deliver five new treatments for drug-resistant infections by 2025, working with 50 public and private sector partners in 20 countries.