Scancell to collaborate with charity CRUK on cancer vaccine

Cancer vaccines have suffered a string of trial failures in recent years, and have fallen behind checkpoint inhibitors and CAR-T at the cutting edge of cancer immunotherapy.

But that could change soon, with a number of companies working on next generation cancer vaccines.

Richard Goodfellow is chief executive of the UK biotech Scancell, which just secured a deal with the charity Cancer Research UK (CRUK) to take a therapeutic cancer vaccine into the clinic, in combination with a checkpoint inhibitor.

CRUK will fund and sponsor a UK-based phase 1/2 clinical trial of Scancell’s antibody-based vaccine SCIB2 in combination with a checkpoint inhibitor in patients with solid tumours, focusing first on non-small cell lung cancer.

News of the alliance gave a huge boost to the share price of the company, which is listed on the London stock exchange, putting it up 11% yesterday.

The charity’s Centre for Drug Development will manufacture clinical trial supplies of SCIB2, conduct and manage the clinical trial, including timelines.

Upon trial completion, Scancell will have the option to acquire rights to the data to support further development, with CRUK otherwise retaining the rights in all indications.

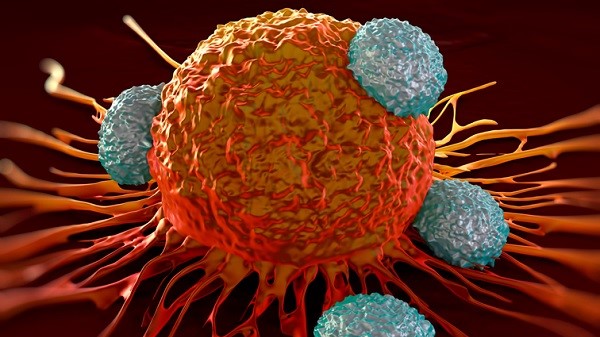

Scancell’s ImmunoBody vaccines target dendritic cells and stimulate both parts of the cellular immune system: the helper cell system where inflammation is stimulated at the tumour site, and the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte or CTL response where immune system cells are primed to recognise and kill specific cells.

SCIB2 works by targeting an antigen called NY-ESO-1, which is expressed on a range of solid tumours, including NSCLC and oesophageal, ovarian, bladder and prostate cancers, as well as neuroblastoma, melanoma and sarcoma.

In an interview with pharmaphorum, Goodfellow said the backing of CRUK was an endorsement of Scancell and its cancer vaccine platform.

Life after Provenge

After years of failures (most notably prostate cancer vaccine Provenge), 2017 has seen a surge of renewed interest in cancer vaccines, thanks to a broad range of more refined and novel drug platforms.

In April, Bristol-Myers Squibb teamed up with France’s Transgene to combine Opdivo with investigational therapeutic vaccine TG4010 in lung cancer.

Meanwhile Germany's CureVac has secured partnerships with Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly for its messenger RNA (mRNA) based cancer vaccines.

However CureVac has suffered its own failure this year when its CV9104 came up short in a phase 2b trial.

And last year NewLink Genetics’ pancreatic cancer vaccine flopped in a large phase 3 study in patients with resected disease.

Most recently, Bavarian Nordic's Prostvac failed its pivotal trial in September.

But Goodfellow insists that there is a future for cancer vaccines now that checkpoint inhibitors are becoming established as standard care in some disease.

Checkpoint combination

Using a vaccine to stimulate the immune system could increase the potency of checkpoint inhibitors and possibly get them to work in patient groups that do not respond.

Scancell CEO Richard Goodfellow

“Cancer vaccines are emerging as great partners for checkpoint inhibitors,” said Goodfellow

But the failure of other treatments has made it difficult to attract investors, he said.

“We have been through a very bad period in cancer vaccines. We always predicted that they (Scancell's rivals) would fail. That creates an environment where it’s difficult to attract partners.”

But thanks to the deal with CRUK, development of SCIB2 can now begin, leaving Scancell free to work on its two other pipeline drugs, SCIB1 and Moditope.

SCIB2 will likely be tested with either Merck’s Keytruda (pembrolizumab) or BMS’ Opdivo (nivolumab), with the former being most likely as its dosing schedule every three weeks initially matches that of SCIB2.

If the trial is a success and Scancell takes the option, Scancell will either invest in more studies itself or find a pharmaceutical partner, depending on the strength of the data.

Scancell will also have to pay a “modest” option fee and milestone payments to CRUK and royalties should the product make it to market.

Goodfellow concluded: “Getting their (CRUK’s) approval is not a trivial matter. If we had done this ourselves it would have cost £5 million and that money can be spent on other things.”