Pharma in a spin as it tries to gauge Trump tariffs impact

Pharmaceuticals are exempt from the cascade of 'Liberation Day' tariffs revealed by President Donald Trump – for now – but the industry is nonetheless bracing for the fallout from what may now become a global trade war.

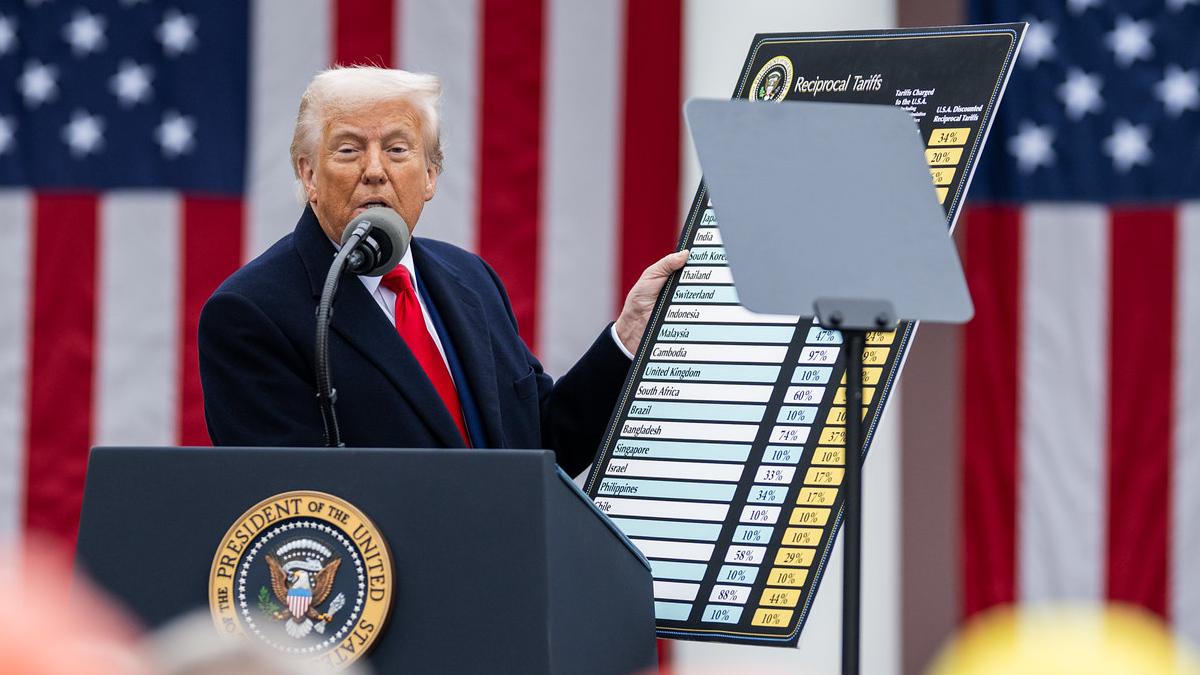

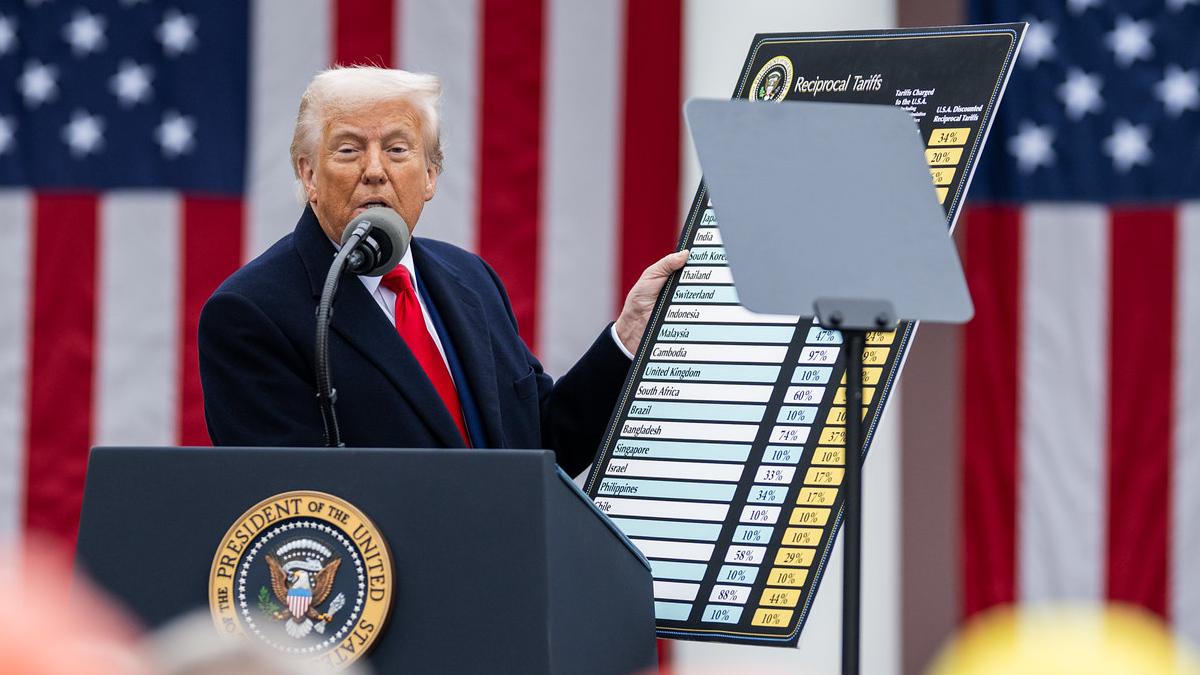

The US president sent a shockwave across the world economy last night after announcing a flat 10% tariff on all imports, with considerably higher rates for countries that the White House believes are the biggest culprits in perpetuating what Trump called "horrendous imbalances" in bilateral trade. In other words, they impose higher tariffs on the US than vice versa or impose other barriers to US trade.

The overarching aim, according to the President, is to bring manufacturing back into the US, protect US jobs, and eradicate the US trade deficit, while also raising tax revenues. Critics say that, for consumers, that will mean reduced choice, higher prices, and potentially higher interest rates, while US exporters are likely to be hit by tit-for-tat tariffs imposed by other countries.

While the UK remains among the countries in the 10% bracket that comes into force on 5th April – and Downing Street is continuing to push for an eleventh-hour trade deal – the EU is facing a 20% rate, India 26%, and China 54%, deemed to be among the "worst offenders," and will see the new levies imposed from 9th April.

Russia has escaped a tariff, which the White House claims is because there is no imbalance, given trade between the countries is practically zero, while Ukraine is included in the 10% group. Meanwhile, the EU, China, and others are already threatening retaliation.

How long will pharma's exemption last?

According to a fact sheet published by the Trump administration, pharmaceuticals are among a group of industries – along with copper, lumber, semiconductors, energy, bullion, and some minerals not available in the US – that are exempted from the tariffs. Shares in AstraZeneca and GSK both rose this morning after news of the exemption emerged.

The big question is what comes under the category of pharmaceuticals. While that almost certainly includes any finished medicines, the prospect of levies being applied to ingredients and components used in their production raises the risk of escalating manufacturing prices for drugs made in the US.

Last month, the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) warned that tariffs on goods coming into the US could have a profound and damaging impact on the biopharma sector, as almost 90% of its member companies rely on imported components for at least half of their FDA-approved products.

Meanwhile, Trump raised the topic of pharma in comments made whilst introducing the tariffs yesterday, saying that he expects manufacturing to come "roaring back" to the US. Some drugmakers – notably Eli Lilly and Johnson & Johnson – have already gone public with commitments to invest in new manufacturing facilities within the US.

However, he also threatened action if companies do not relocate plants in the US, with some predicting that the sector could still be faced with phased introductions of separate, targeted tariffs – with the delay only because it is well-known that it can take a long time to move production in a highly-regulated industry like pharma.

A Reuters report citing sources close to the White House discussions has suggested that a previously discussed 25% rate on medicines will eventually be introduced with a gradual ramp-up.

Some countries – including Ireland, which has a high density of US-owned facilities and exported $63 billion in drugs to the US last year, and India which is a massive supplier of generics to the American market – remain very nervous about what might be coming down the line.

One reason US manufacturers have flocked to Ireland has been its favourable tax regime, allowing them to lower their overall tax burden, and that could backfire if tariffs are applied.

There are also deep concerns that pharma tariffs will lead to escalating medicine prices in the US, which will be borne by patients, while some drugs may become unavailable if overseas producers decide it is no longer economically viable to supply the US market. At the moment, almost a third of medicines used in the US are imported – roughly $200 billion out of $560 billion consumed in 2024.

So far, big pharma companies and industry associations are largely keeping quiet on the tariffs, likely due to the lingering uncertainty about what is in store. The PhRMA said it will "look forward to working with the administration on ways to ensure America remains the most attractive place in the world to discover and manufacture new treatments and cures."