J&J vaccine fails to protect women against HIV infection

Johnson & Johnson's HIV vaccine candidate has failed its first major efficacy test, as it was unable to protect women against infection with the virus in a phase 2b trial carried out in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Ad26.Mos4.HIV vaccine – which uses the same adenoviral technology as J&J's COVID-19 vaccine and targets four HIV antigens – showed that the shot was safe, but unable to meet its target of reducing transmission of HIV by 50% in the Imbokodo trial.

The primary analysis of the results indicated a protective efficacy of just 25% in the study, which enrolled 2,600 women at very high risk of HIV infection, after two years' follow-up.

At the end of that period, 63 subjects who received the placebo and 51 participants who received the experimental vaccine had acquired HIV, according to researchers from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which supported the trial along with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

According to UNAIDS, women and girls account for nearly 60% of people living with HIV in eastern and southern Africa.

Earlier clinical results suggested that Ad26.Mos4.HIV was better at stimulating antibodies against HIV than an earlier version that targeted three antigens.

The trial has now been discontinued, but a different version of the vaccine is still being tested in the phase 3 Mosaico HIV study, involving men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender individuals in the Americas and Europe.

As the vaccine is different, and different strains of HIV are circulating in these regions, the decision has been taken to continue Mosaico, although there's no disguising that the Imbokodo results are a massive blow to the programme, which is due to read out in 2024

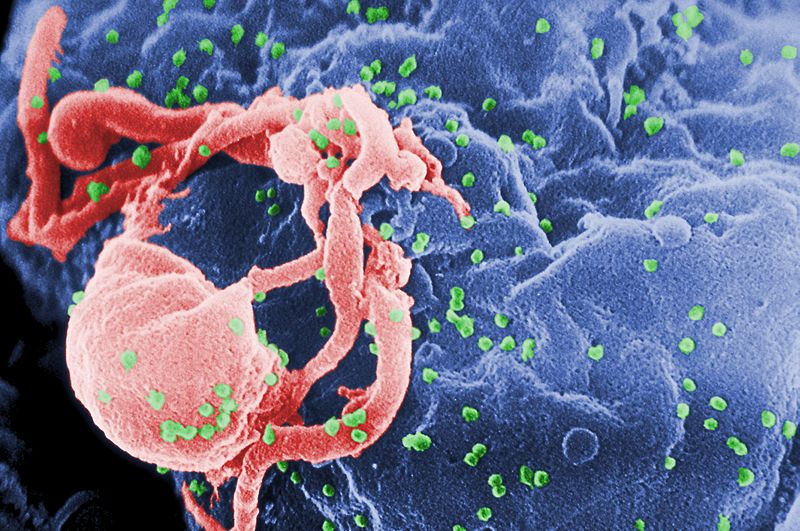

"HIV is a unique and complex virus that has long posed unprecedented challenges for vaccine development because of its ability to attack, hijack and evade the human immune system," said J&J's chief scientific officer Paul Stoffels.

"While we are disappointed that the vaccine candidate did not provide a sufficient level of protection against HIV infection in the Imbokodo trial, the study will give us important scientific findings in the ongoing pursuit for a vaccine to prevent HIV," he added.

Antiretroviral drugs can keep HIV under control in people already infected with the virus – if they can get access to them and comply with treatment – but there's still no cure and therefore a critical need for a vaccine that can prevent new infections.

Despite more than 30 years of research, the tendency of the virus to mutate means that classical approaches to vaccine design have been ineffective, and at least four prior vaccine candidates have failed in clinical trials.

Earlier this year, the HVTN 702 study of two co-administered HIV candidate vaccines from Sanofi Pasteur and GlaxoSmithKline, combined with GSK's adjuvant MF59, was also discontinued due to a lack of efficacy.

"The development of a safe and effective vaccine to prevent HIV infection has proven to be a formidable scientific challenge," said Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID).

"Although this is certainly not the study outcome for which we had hoped, we must apply the knowledge learned from the Imbokodo trial and continue our efforts to find a vaccine that will be protective against HIV."