Buyer’s remorse: The UK’s VPAG

Leela Barham takes stock of the debate surrounding the UK’s current pricing and access deal that caps NHS spend on branded medicines, after a higher-than-expected payback rate for 2025.

With the ABPI wanting to change the scheme just over a year into its five-year term, it seems that they have buyer’s remorse.

Cap on NHS branded medicines spend for over 10 years

The UK’s Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAG) was agreed upon by the ABPI, the research-based industry association, and the UK government and NHS England in 2023.

The scheme has three objectives:

•Promote better patient outcomes and a healthier population

•Support UK economic growth

•Contribute to a financially sustainable NHS

The current scheme opened on 1st January 2024 and is due to run until the end of 2028. It’s just the latest in voluntary agreements that have been in place since the 1950s. VPAG, like predecessor agreements since 2014, caps NHS spending on branded medicines.

The cap is the main way that VPAG contributes to the financial sustainability of the NHS (although, it’s not the only way that the UK influences spending on branded medicines). Before then, the scheme had primarily focused on profit control, albeit with price cuts, too.

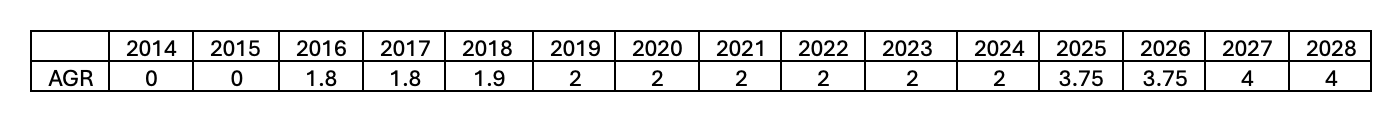

The voluntary scheme cap works one way; there is no guarantee that the NHS will spend a particular amount on branded medicines, but there is a guarantee that the NHS will spend no more than the amount implied by a negotiated - “allowable” - growth rate in the branded medicines bill. It was 2% in 2024, rising to 4% by 2027. The rates in the current voluntary scheme are higher than they have been in the past (Table 1).

Table 1: Allowable growth rates under voluntary schemes, 2014 to 2028

AGR = Allowed Growth Rate of Measured Spend

Sources: PPRS 2014, VPAS 2019, and VPAG 2024

The cap is operationalised by companies having to pay back a percentage of their sales, set at a rate to cover the amount that NHS branded medicines spend will be over and above the agreed growth rate. In a break from previous schemes, the rebate rate in VPAG differs according to whether companies have older or newer medicines in their sales.

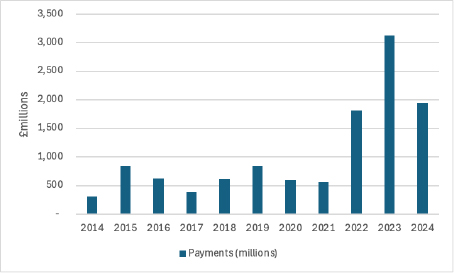

The absolute amounts paid back have been rising over time (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Payments under voluntary schemes, 2014 to 2024

Source: PPRS aggregate net sales and payment information, VPAS aggregate net sales and payment information, and VPAG aggregate net sales and payment information

The ABPI has said that the 2025 payments could reach £3.5billion. If they do, that would be the biggest annual payback ever.

At the time that VPAG was agreed, the government described it as a “pro-innovation and pro-competition agreement.” The ABPI described it as a “tough deal.”

Unpredictable rebate rates for over ten years

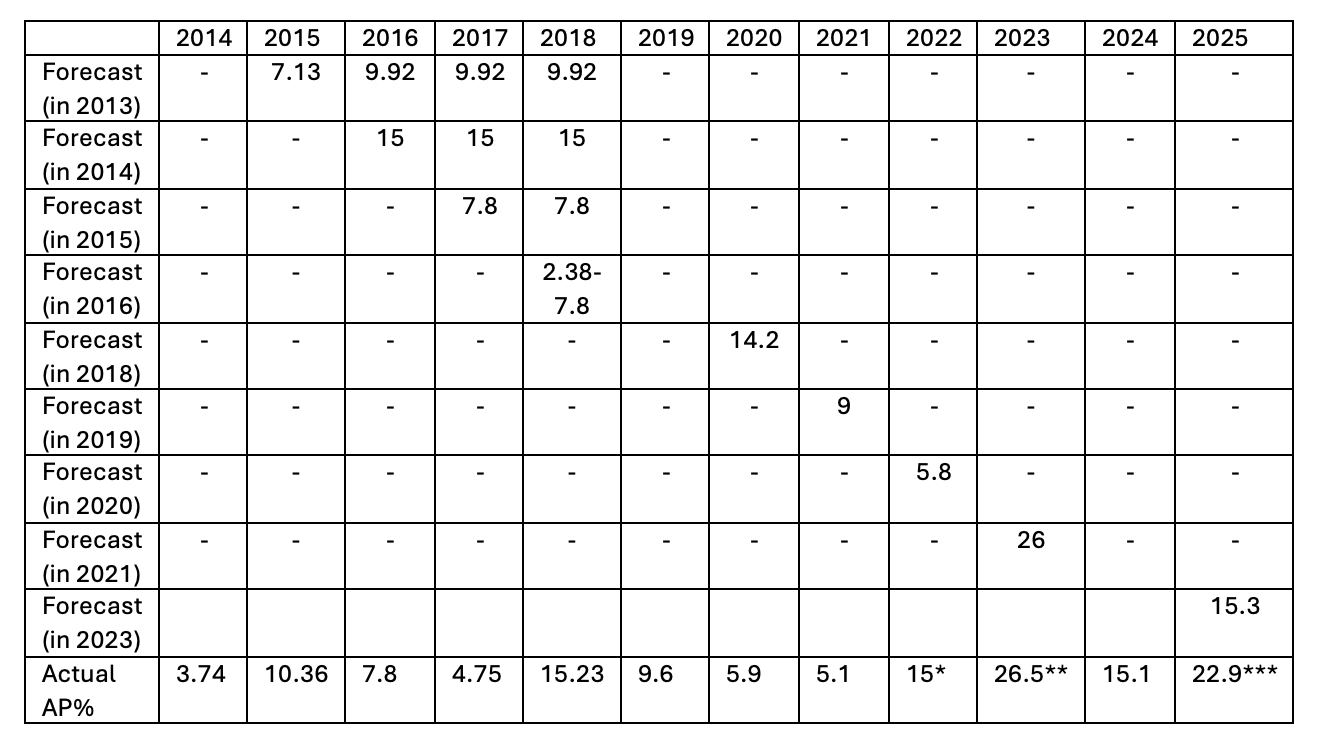

The first year of VPAG set out a payment percentage for new medicines and then it is calculated for each subsequent year by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) based on sales data submitted by companies. As part of the number crunching, the DHSC has also set out forecasted rates, just as it has done for voluntary schemes (Table 2).

Table 2: Forecasted and actual rebate rates for new medicines under Voluntary Schemes, 2014 to 2025

AP% = Annual Payment Percentage

* This was an agreed fixed rate which should have been 19.1% based on scheme calculations. The rate was agreed upon on an exceptional basis reflecting rapid growth in sales in 2021

** 2023 reflected a catch-up for the lower rate in 2022

*** This rate reflected an underpayment of £373 million underpayment in 2024 following recalculations based on the most recent data. The most recent data would have meant that instead of 15.1%, it should have been 21%

In reality, forecasts for rebate rates have been wrong - and often out by a lot - more often than right. Only in 2023 was the forecasted rate close to the actual rate. That, in part, reflects adjustments agreed to the 2022 rate because scheme calculations were temporarily overwritten, given higher spending on branded medicines during COVID-19.

That the DHSC has struggled to forecast accurately means that they are experiencing the same challenges everyone else does. A review of methods for projecting public spending on pharmaceuticals undertaken by researchers at the Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre, published in January 2025, pointed out that there are no best-practice forecasting methods established. Where forecasts had been compared to actual expenditure, the largest errors came from “new market launches and unforeseen policy reforms.”

For member companies, it’s difficult to know what will become due each year and over the lifetime of a scheme.

Things have changed

The ABPI has said that assumptions made at the time they agreed on VPAG in 2023 haven’t held in reality. Specifically: “The NHS has received more funding from the government than was assumed to be the case in 2023 during VPAG negotiations. Greater funding has led to more NHS activity and, ultimately, a greater demand for medicines, which must be paid for by the industry.”

Greater use of medicines is the very effect that the voluntary schemes should have had in any case, just as Mark Davis, from public affairs agency Shape Health, pointed out in a LinkedIn post. “We have had a negotiated pricing scheme in price that is intended to incentivise the NHS to use more medicines,” he wrote. “[N]ow it seems that the NHS has finally woken up to the opportunity.” But why not? And will this persist?

The challenge comes from when NHS spending on medicines reaches a point that is unsustainable for industry, Davis argued.

To fix this “problem”, the ABPI wants the allowed growth rate to be adjusted now and into the future, linked to the planned NHS budget. It also wants the scheme to “move away from a hard growth cap.”

Consequences, consequences

The ABPI has been vocal about what it sees as the consequences of VPAG and previous schemes. In March, the association highlighted how England’s record on new medicines availability has worsened over the last ten years, the UK has fallen down on the league table for the number of phase III trials hosted, and the UK’s falling share of global R&D investment in the last three years.

Guy Oliver, general manager for Bristol-Myers Squibb UK and Ireland, also pointed to a “decrease in the launch of innovative medicines, cuts to partnerships supporting the NHS, and workforce reductions across the sector.” Less investment was also a warning from Laura McMullin, general manager at Daiichi Sankyo UK. Plenty of other companies have added their voices too.

Case for change?

On the one hand, there might be little sympathy for what amounts to the ABPI wanting to take back the VPAG and get a new one. The ABPI agreed to VPAG - and predecessor schemes - which left member companies paying an unknown amount back to the government. That companies are paying more than expected isn’t new. Forecasts have been wrong in the past.

On the other hand, with ten years of experience with schemes like VPAG, some trends can be looked at for all the other things that matter, beyond the money, just as the ABPI and individual companies have been doing.

Then, there’s the international perspective; the ABPI has been highlighting how the UK compares to other countries in terms of rebate rates. The UK is high compared to Germany (12%), Spain (7.5%) and Ireland (8.25%); it has to compete on the global stage for industry investment, after all. The ABPI has said that the “medicine levy makes the UK un-investable.”

There will be knock-on effects if VPAG is materially changed. Perhaps most tangible will be changes to the statutory scheme for branded medicines pricing. It’s a backstop, which applies to companies who choose not to join VPAG. The government has always said that it wanted the statutory scheme to be broadly commercial equivalent to the voluntary scheme. A consultation on the statutory scheme is ongoing that is proposing a rebate rate of 23.8% in 2025, 24.7% in 2026, and 26.4% in 2027.

What the other consequences could be will become evident over time, that is if the VPAG has been a key driver – even if not the only driver – of where companies choose to invest and launch new medicines. There will be a calculation that the government has to do; will the pounds and pence given up by loosening the cap now, pay off in the future?

June review

The original VPAG included two planned reviews of the scheme, one in autumn 2025 and the other in spring 2027. The government and the ABPI have agreed to bring the first one forward, with the review due to report in June. That will coincide with a new 10-year plan for the NHS and a Life Sciences Sector Plan. The review, according to text in VPAG, could allow for “changes to scheme terms,” with changes only being “made with the agreement of both Parties.”

According to the ABPI, this review will “focus on addressing shared concerns across government and industry about the significantly higher than expected ‘headline payment rate’ for newer medicines in the scheme to restore its predictability and sustainability.”

The ABPI’s David Watson, executive director for patient access, shared on LinkedIn on 10th April that the ABPI is doing a “sprint process” to work with the government to identify and agree workable solutions. The aim, at least for the ABPI, is to “get the newer medicines VPAG payment rate back to internationally competitive levels.”

ABPI’s chief executive, Richard Torbett, said: “Wes Streeting has made clear his determination to work with our industry to address existing commercial challenges while also setting out a bold vision to transform the way the health system values medical innovation. The first step is to address high and unpredictable medicine payment rates in June, so we can then power forward to support the NHS 10-year plan and deliver the government's upcoming life sciences strategy.”

Presumably, Streeting will need to get HMT on the side to any changes, too.

Will a new iteration of the voluntary scheme strike the right balance to achieve not only a financially sustainable NHS, but also better patient outcomes and a healthier population, as well as support UK economic growth?