End-of-life treatments: what will NICE accept?

As consultation on the 'new' Cancer Drugs Fund closes this week, Leela Barham reviews the impact of England's guidance on end-of-life treatments and the implications of these broader changes.

Six years ago flexibility was introduced to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) process when considering drugs for patients close to death. This may change soon, as NICE and NHS England (NHSE) (which pays for chemotherapy) are consulting on a 'new' Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) (closing on 11 February 2016).

But what has this flexibility meant for the increasingly important NICE recommendation? And how could the changes proposed to End-of-Life (EoL) guidance affect future recommendations?

A willingness to pay more...

The idea that there could be a greater societal willingness to pay for treatments that may extend life when death is near is controversial; some have highlighted the potential for health losses from prioritising these treatments over others.

However, this option was formally introduced into NICE appraisals in January 2009. Supplementary guidance is used by Appraisal Committees (ACs) to help them in their deliberations when such treatments are considered.

....in some circumstances

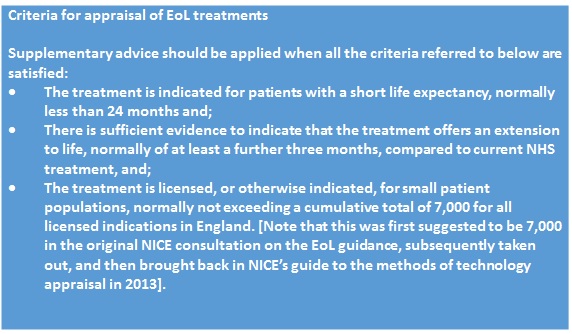

There are criteria set out for when NICE ACs can take a more flexible approach to treatments at the end of life (Box 1).

Box 1. Sources: NICE, July 2009 and NICE, 2013.

These criteria are just part of the advice, though; even if these are met, the AC will also consider:

• The impact of giving greater weight to quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) achieved in the later stages of terminal diseases, using the assumption that the extended survival period is experienced at the full quality of life anticipated for a healthy individual of the same age; and

• The magnitude of the additional weight that would need to be assigned to the QALY benefits in this patient group for the cost-effectiveness of the technology to fall within the normal range of maximum acceptable incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs).

Further, the AC needs to be 'satisfied' that the estimates of the extension to life are robust and assumptions used in the reference case economic model are plausible, objective and robust. So, all in all, this amounts to the potential for flexibility – and much potential not to apply it in practice.

An average £49,000 per QALY...

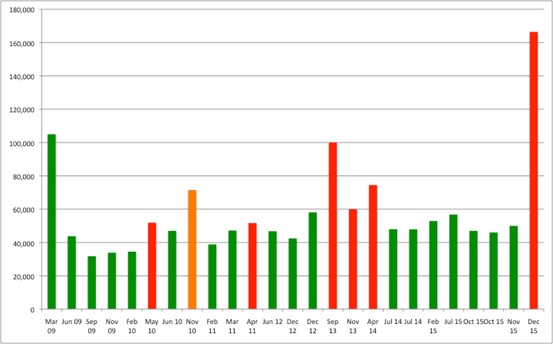

By reviewing all current NICE Technology Appraisals (TAs) it's possible to work out just how much more NICE AC's have been willing to accept for EoL treatments. NICE has applied EoL flexibilities in 25 TAs since the guidance was introduced. Of those, 18 have resulted in NICE recommending use (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Best estimates of cost per QALYs and NICE TA recommendations, applying EoL guidance, 2009 to 2015

Source: Analysis of data from NICE

Note: Green = Recommended, Red = Not recommended, Orange = Restricted recommendation

Although the EoL guidance might focus on the weight needed to apply to QALYs, in practice (and because of the arithmetic at play) what really matters is the cost-effectiveness threshold used when ACs consider these treatments. The magic number, based on an average across all positive recommendations, seems to be around £49,000 per QALY. This could explain previous suggestions, made by NICE itself, that there is a limit of £50,000 per QALY when appraising EoL drugs. However, in practice, there is still variation and much will rest on the broader package of evidence and deliberation (and that is no bad thing; the cost per QALY should be but one aspect to consider).

...but only when NICE is convinced that EoL applies

In a further 29 TAs EoL was discussed but dismissed. The reasons aren't always clear from the guidance, but they included clear failure to meet the criteria (in 16 of the 29 TAs) or concerns about the robustness of data (in 10 of the 29 TAs). In three cases, the guidance discussed EoL but noted that the company didn't make the case for the flexibility to apply. However, in seven TAs, NICE made either a positive or restricted recommendation, so EoL flexibilities aren't always needed anyway.

A close look at the TA guidance that references EoL guidance also makes it clear that interpretation varies by AC. For example, in TA257, looking at tratuzumab, the AC was not convinced that 7,000 was a small population or that patients in clinical trials should be taken out of the calculation of population size. The same guidance notes that another AC had accepted 7,158 as a small population and that patients in clinical trials could be excluded. The guidance states that 'these different conclusions were matters of judgement' and, in the end, the AC did accept that the patient population was small.

In TA360, looking at paclitaxel, extension to life was estimated to be 2.4 months. This is below the three-month criterion yet, on this occasion, and in light of the very poor survival of those with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, it was accepted. So even with relatively clear criteria, application still allows for context.

Changes to EoL guidance

EoL is perceived as an important flexibility in how NICE approaches decisions. It taps into a wider debate about how well, or not, tools used by NICE capture what those with a condition, and their loved ones, believe are important when it comes to these decisions.

When NICE tried to change it in 2014, in the painful debate that was Value Based Assessment (VBA), many were concerned. The idea was that changes such as adding in burden of illness would incorporate EoL considerations. But the fear was that it would be lost. At the very least, critics were right that it would become less transparent. Those proposals were later dropped by NICE amid calls for a bigger debate.

Now, with the CDF under pressure, NICE and NHSE have put forward a revised version of EoL guidance. This would take away the need to consider the cumulative size of the patient population and 'emphasise the discretion that exists for NICE ACs'. The cumulative size of the patient population has stopped EoL being applied in four TAs; granted, this is not that many, but it is important for the patients and companies concerned.

So this change could be significant and perhaps help a small number of drugs achieve a positive recommendation. However, because the proposals for a new CDF are far-reaching, it might not really make any difference.

The consultation closes this week, on 11 February, so we'll find out how EoL guidance will be changed then, or soon after.

About the author:

Leela Barham is an independent health economist and policy expert who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally. Leela works on a variety of issues: from the health and wellbeing of NHS staff to pricing and reimbursement of medicines and policies such as the Cancer Drugs Fund and Patient Access Schemes. Find out more here and you can contact Leela on leels@btinternet.com.

Read more from Leela Barham: