Countdown to pharma disclosure in Europe – but cultural divides remain

Pharma is getting ready to disclose full data on payments to doctors across Europe for the first time – but big cultural differences across the continent will complicate matters.

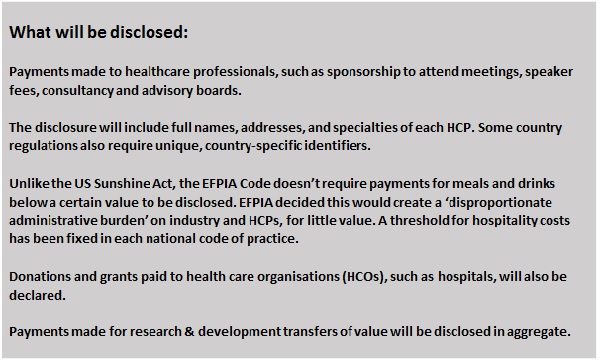

The pharma industry is just months away from laying bare its relationships with doctors in Europe, revealing for the first time the names of doctors, how much individual pharma companies have paid them, and for what. From 30 June 2016, all pharmaceutical companies will be required to publish payments made in the previous year to doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals (HCPs), and identify them by name wherever possible. The new rules will also include payments to hospitals and other healthcare organisations (HCOs) across 33 European countries.

This represents a watershed moment for pharma's relationship with doctors, and reflects a global move towards greater transparency – the US and Australia having already launched their own 'Sunshine' laws.

EFPIA, the pharma industry representative body for Europe, agreed the voluntary code with 33 member organisations across the continent several years ago, and the industry has been preparing ever since.

Not surprisingly, there are some worries about what will happen in June: will every pharma company disclose its data on time? Will doctors protest against having their details published? And, most importantly, will disclosure actually stoke public suspicions about inappropriate influence, rather than allay fears?

One thing is clear – across a continent with such diverse cultures and practices, the patterns and levels of disclosure will be far from uniform.

EFPIA's head of communications, Andy Powrie-Smith, has been dealing with industry reputation issues in the UK and Europe for the best part of a decade. He acknowledges that naming HCPs in disclosures is a big step, but says it's a natural evolution for pharma that reflects a societal shift towards ever more transparency in public life.

Speaking at a roundtable event organised by life sciences data specialists Veeva in Barcelona in December, Powrie-Smith was frank that pharma had made mistakes in its relationships with HCPs in the past, but that in recent years these had evolved rapidly. He was equally sure that close relationships between the industry and healthcare professionals remained vital to developing new drugs, and making sure they reached the right patients at the right time.

Shedding light on these relationships would, he believed, allow wider society to understand that the interests of pharma, HCPs, and patients are aligned.

"We need to move from a conflict of interest to a confluence of interest, and transparency helps to do that," he stated.

Also contributing to the roundtable was Walter Chmielewski, transparency manager for Biogen in Europe. He agreed that the momentum towards greater transparency was unstoppable: "We live in a world where everybody wants to know everything about you," he said.

He believed disclosure of data – known as 'transfers of value' (TOV) from pharma to healthcare professionals and healthcare organisations – would one day be a legal obligation. In fact, European-level legislation might even be welcomed by pharma – its task of collecting data, verifying its accuracy, and seeking consent is made more difficult by each country having its own interpretation of the EFPIA code and its own cultural attitudes.

Veronique Monjardet is country manager in France and European lead for pharma compliance specialists Polaris. Despite there being agreement to adopt a common set of rules, the countries have inevitably diverged. Monjardet said rules about gaining consent are a good example of this: many countries (such as the UK) require pharma to get permission from the HCP to publish the data, but others, such as France and the Netherlands, do not.

This will play a big role in determining how many names can be published in each country. In general, the Data Protection Directive allows HCPs to opt out of being identified – and many are likely to exercise this right.

A survey of UK healthcare professionals by the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) last year found that 69% would give their consent. While this represents the majority, it's not a resounding victory for transparency – nearly one-third would refuse to have their details published. This will leave pharma companies with no choice but to publish these payments without identifying HCPs, which will put them into a separate aggregate total of anonymous recipients.

The consent levels could be even lower elsewhere in Europe: a survey in Poland suggests an average consent of 23% (some companies achieving high levels, some much lower), while Germany is likely to reach 40-44%. In Spain, many doctors are refusing to give consent to be named, as they fear being hit by the taxman on this income, which they may not be declaring.

Andy Powrie-Smith is at pains to stress that the EFPIA disclosure code has nothing to do with anyone's tax affairs, but this unintended consequence is the sort of issue that will slow the move to full transparency.

Under the EFPIA agreement, companies are obliged to make their 'best efforts' to achieve full disclosure but, faced with such obstacles, companies will have no choice but to anonymise the payments. The hope is that once HCPs see the system in action, they will be won over to the principles of transparency, and these percentages will rise across Europe.

Huge cultural differences across Europe

Veeva's Guillaume Roussel, who chaired the event, said cultural differences will inevitably mean considerable variation in the levels of disclosure achieved in Europe.

There are, in essence, four different Europes when it comes attitudes to transparency: Scandinavia, north-west Europe, eastern Europe and southern Europe. Roughly speaking, this represents a sliding scale, with Scandinavia the most open, and eastern and southern European countries more resistant to disclosure.

The Scandinavian countries are renowned for having embraced transparency in public life. An example of this is that in Sweden, Norway and Finland, everyone's income and annual tax returns are published online for all to see.

By contrast, countries in southern and eastern Europe, such as Greece, Serbia and Russia, have had major problems with corruption, including numerous criminal investigations into bribery of HCPs and officials by pharma and medical device companies, which have occurred over the last 10 years.

France was rocked by the scandal around Servier's Mediator, publicly disclosed in 2009, which resulted in a whole new regulatory system and legislation making disclosure of payments obligatory, with Portugal, Denmark and Slovakia having similar laws. Meanwhile, Estonia, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania and Serbia all have legislation in the pipeline covering disclosure of payments, which should help them eventually close the gap on the leading countries.

Are you ready?

So will every pharma company be ready to disclose its data by 30 June? A survey conducted by Veeva last year suggested that many were struggling to accurately capture data across their systems. Nevertheless, Andy Powrie-Smith is confident that companies will meet the deadline, as transparency has become a major reputational issue for the sector.

Collecting data, ensuring its accuracy and gaining consent to publish it is a huge undertaking for companies. Walter Chmielewski pointed out that central to this is creating a 'golden thread' that allows companies to accurately track payments to each individual HCP, regardless of what the transfer of value was, or which division or country affiliate made the payment.

He said that the drive to meet the deadline, and to resource all the work, came from the very top of Biogen's leadership.

"Our management were very much in favour of embracing transparency. It involves a lot of effort within organisations, with a lot of dollar value and human resources being devoted to it."

On the question of some HCPs refusing to have their names published, this could certainly be a focus for attention after 30 June. Of course, this is out of the industry's hands, but may, nevertheless, see suspicions directed at pharma as much as these doctors. If, on the other hand, a company is found to have not disclosed all the relevant data, it could face serious censure or even fines, depending on the country involved.

The other question posed earlier was whether disclosure would actually stoke public suspicions about inappropriate influence, rather than allay fears. Polaris' Veronique Monjardet said that, despite the high profile of the Mediator scandal, the response to disclosure was muted: "When the moment came, there were no big headlines."

Pharma companies braced for a backlash elsewhere in Europe after 30 June may well experience the same anti-climax. But probably the single most important question is whether the new rules will actively help prevent these inappropriate relations in the first place.

In reality, they are unlikely to be foolproof – recent corruption cases have shown that those intent on breaking the rules can usually find ways to work round them. For that reason the 30 June deadline doesn't represent a 'finishing line' for efforts with transparency and appropriate relationships; rather, it is just the beginning of a new era with a continued focus on higher standards.

Further reading

EFPIA: All Roads Lead to Consent - Veronique Monjardet, Polaris, 5 January 2016

Recent evolutions of the 'French Sunshine Act' (Lexology)

About the author:

Andrew McConaghie is pharmaphorum's managing editor, feature media.

Contact Andrew at andrew@pharmaphorum.com and follow him on Twitter