The future of cancer care

In our oncology themed month, Professor Karol Sikora of Cancer Partners UK offers a glimpse into the cancer treatment environment of tomorrow and why he thinks we will see huge advances in cancer treatment in the next decade.

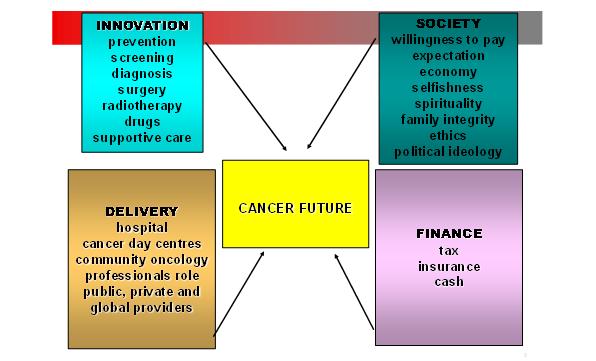

Cancer incidence is rising in rich and poor countries alike. The main driver is a gradual increase in the age of populations. This is a triumph of both medical technology and public health. But living longer brings new problems both for healthcare systems and society. How much is it worth keeping Granny alive? There are four components to the future of cancer care (Figure 1). The boxes are intertwined – new technology is guaranteed but the ability of society to pay for highly individualised cancer treatments is not. A sustainable financial system together with an effective service distribution network has to be in place.

Figure 1: The future of cancer care has four main components – technical innovation, societal change, optimal delivery of care and financial mechanisms to pay for everything.

The ability of technology to improve health is assured. But it will come at a price – the direct costs of providing it and the care costs of the increasingly elderly population it will produce. We will simply run out of things to die from. New ethical and moral dilemmas will arise as we seek the holy grail of compressed morbidity. Living long and dying fast and cheaply will become the mantra of 21stcentury medicine. Medicine's future will emerge from the interaction of four factors: the success of new technology, society's willingness to pay, new healthcare delivery systems and the financial mechanisms that underpin them. Let's examine the technology and leave to societal impact to the politicians.

"A sustainable financial system together with an effective service distribution network has to be in place."

The new diagnostics – imaging and molecular probes

The reduction in waiting times throughout global healthcare systems has improved the speed of cancer diagnosis, but there are still delays in obtaining imaging, such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET) scans. Furthermore, expert histopathology is critical to getting a precise diagnosis and capacity problems in many diagnostic laboratories are causing delays to getting started on treatment. The key to the future in all healthcare systems is up-front personalisation of therapy based on good diagnostics. Oncologists have actually been very good at this despite limited data. In breast cancer, adjuvant chemotherapy is personalized by the risk of recurrence. Sophisticated clinical tools such as www.adjuvantonline.com have, for some years, used clinical and pathology derived data to optimise the choice of drugs following surgery for breast cancer. But for most cancers we need something better.

Molecular signatures of response to high-cost targeted drugs that are easily determined by tissue analysis are urgently needed. All hit well‑defined molecular targets for which functional assays are available (Figure 2). After all, such assays are an essential part of their discovery process. The activity of downstream signaling cascades can now be determined in clinical samples, provided repeat tissue samples can be obtained after drug administration. Such assays could provide not only the very signatures required, but also effective surrogates of early response. And there are examples where translational data could lead to new targeted drug combinations where two pathways are blocked simultaneously. Within the next five years, phase III trials will look very different to today. Only patients whose tumours express the relevant biomarker pattern suggestive of response to a new agent will be entered. After 24 hours of drug administration, validated response surrogates will be measured. Those patients testing negatively will be removed from the study and offered either alternative medication or supportive care. By such a dual selection programme, the active arm of the new phase III programme will be fully enriched for responding patients, making drug development faster, cheaper, and more beneficial for those enrolled.

Figure 2: Staining breast cancer tissue for the receptor that binds to Herceptin

The costs of the diagnostics for personalized medicine may be high, but the potential for savings on the drug bill is enormous. No payer is going to ignore this. The days of marketing cancer drugs like a supermarket commodity are over. Developing ways to optimise responses through companion diagnostics and short‑term surrogate biomarkers are now going to be essential.

"We will simply run out of things to die from."

New drugs

This is an exciting time for those involved in cancer research and care. But the cost of getting a single drug to market now exceeds $1 billion per compound. More sophisticated molecular diagnostics are being developed, which will shortly be able to personalise care, increasing its cost-effectiveness. Giving the right medicine to the right patient will eventually drastically reduce the overall costs of care, but we are not there yet.

There's a lot of excitement about chemotherapy now based on human genome programme, bio-informatics, robots for high throughput screening, computer drug design and whole platforms such as the kinases for which to create drugs. New biomarkers identifying pharmaco-dynamic end points are now available so we can actually measure if the drug is hitting on its target by just taking a sample of tissue from the patient. We now have surrogate end points and molecular signatures to predict response to different agents. The pathology of the future is not going to be about microscopic morphology, it will be about identifying molecular patterns that rationally guide therapy.

Figure 3: Modern radiotherapy precisely targets the tumour and yet effectively spares the surrounding organs at risk

There are currently just over 800 drugs in clinical trial for cancer of which about 500 are against very specific molecular targets. By 2022 there will be 2,000 compounds and probably by 2025 there will be 5,000 compounds. There are patterns evolving as the drug industry really has very little imagination. At the moment the main theme is small molecules. Monoclonal antibodies, cancer vaccines and gene therapy are on trial on a smaller scale but the emphasis is on small molecules.

"The key to the future in all healthcare systems is up-front personalisation of therapy based on good diagnostics."

Conclusion

Over the next decade, I believe we are going to continue to make tremendous strides in the treatment of cancer. And local treatments with surgery or radiotherapy will dramatically improve with new technology. It will become more prevalent throughout society as we all get older. But will also become more treatable. It will move from being a fatal to a chronic disease like diabetes or hypertension.

About the author:

Karol Sikora is Medical Director of Cancer Partners UK a group creating the largest independent UK cancer network. He was Professor and Chairman of the Department of Cancer Medicine at Imperial College School of Medicine and is still honorary Consultant Oncologist at Hammersmith Hospital, London.

Will cancer move from being a fatal disease to a chronic disease like diabetes or hypertension?