NICE feedback?

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is quite far along a NICE-led process to review its methods and processes for evaluating technologies. As part of that work, NICE is engaging widely with stakeholders, including patient organisations. Leela Barham provides an independent view of patient organisations responses to a NICE online survey and highlights the opportunity for other stakeholders to share their views on NICE through an online survey open until 16 July 2021.

The NICE patient involvement team has had a workstream relating to public and patient involvement in NICE’s review work on evaluating technologies since 2018. That work includes patient groups in the know, having participated in NICE’s work, but has also included an online survey to bring in wider views. The survey was run in July 2019.

The results of that survey are publicly available; albeit tucked away on the part of NICE’s website dedicated to public and patient involvement and not linked to on the part of NICE’s website dedicated to the ongoing reviews, so are easy enough to miss. But the results should be key reading for stakeholders who want to see patient organisations become more involved at NICE. Hard to know exactly when the report was published; there’s no date on the report of the survey done by NICE.

Key messages from patients who have worked at NICE

It’s not easy for patients to be involved with NICE’s work

NICE has recognised the message that there is more that needs to be done about the ease of working with NICE; 20 per cent of respondents said it is easy for patient experts (individual patients who may be asked to share views with Appraisal Committees) and 35 per cent of respondents said it is easy for patient organisations to get involved in the development of guidance. That’s an awful lot who found it must have at best been neutral and at worst, found it hard to get involved in NICE’s guidance work.

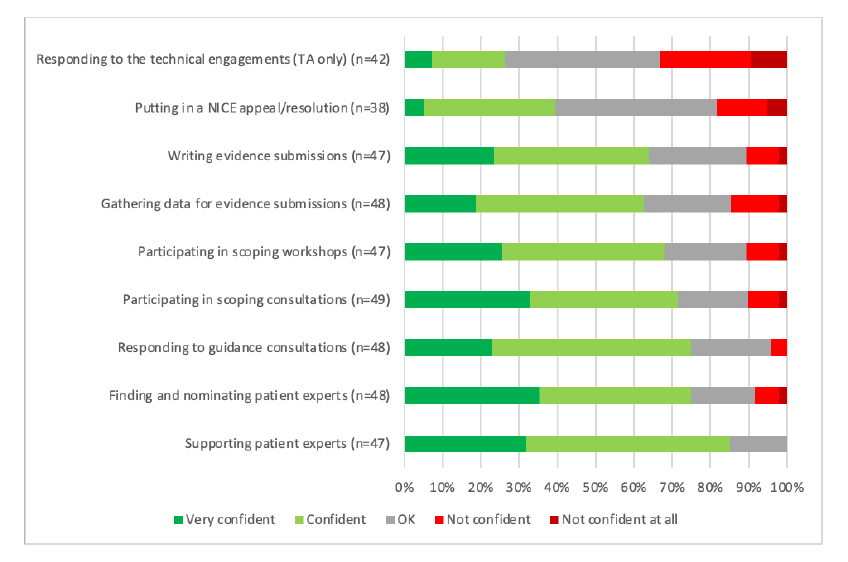

Appealing NICE decisions and technical engagement is challenging

NICE points to the higher proportions that focus on the good news for the organisation but also recognises some of the less positive messages. Patient organisations struggle with what might be seen as the really hard stuff; challenging NICE through appeals (you can only imagine the paperwork that involves let alone understanding the criteria for appeals and processes) as well as the difficulty in contributing to the technical engagement opportunities that NICE can provide. This technical engagement can cover issues like survival modelling; not an area that many people will have real expertise in, even less for patient organisations.

Figure 1: Patient organisation respondents views on confidence in NICE processes

Note: Data from NICE (Undated) Improving meaningful public involvement in NICE medicines and technologies guidance. Note: TA = Technology Appraisal

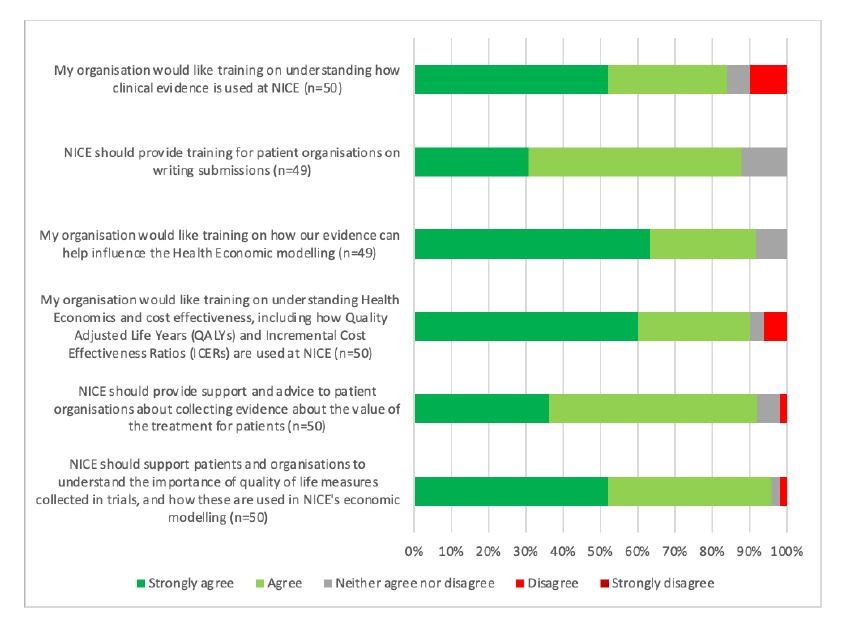

That there is a challenge relating to the technical side of NICE’s decision making was echoed in the areas that patient organisations who responded were looking for further training (Figure 2). It does beg a question though; should it be for patient organisations to clue themselves up on these technical areas or is it for the experts who are doing them and those using them in decision-making to communicate them more clearly?

Figure 2: Patient organisation respondents views on areas for support and training

Note: Data from NICE (Undated) Improving meaningful public involvement in NICE medicines and technologies guidance.

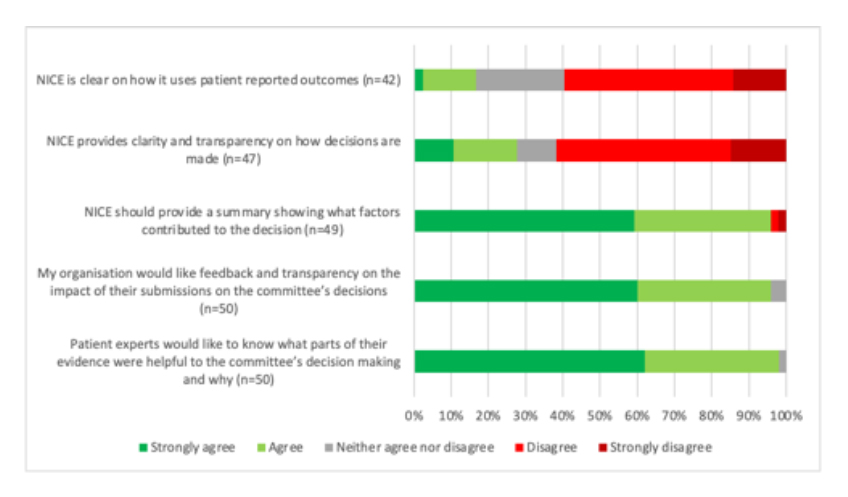

Decision making is not transparent to patients and patients can’t see what difference they make

A difficult message for NICE to hear comes through in terms of transparency for why NICE committees make the recommendations that they do. Not only that, but from a patient expert and patient organisation perspective, it’s not clear what difference their input makes (see figure 3). Perhaps that’s why, for some appraisals, not all patient organisations provide a submission. Patient organisations’ own, albeit informal, cost-benefit analysis of engaging presumably plays in. If they can’t see what difference they make, then why bother? This needn’t mean that they only see the benefit when they get a ‘yes’ but rather that they can at least feel that they get a fair opportunity and can see the logic in a decision that is reached.

Figure 3: Patient organisation respondents views on transparency and impact on NICE

Note: Data from NICE (Undated) Improving meaningful public involvement in NICE medicines and technologies guidance.

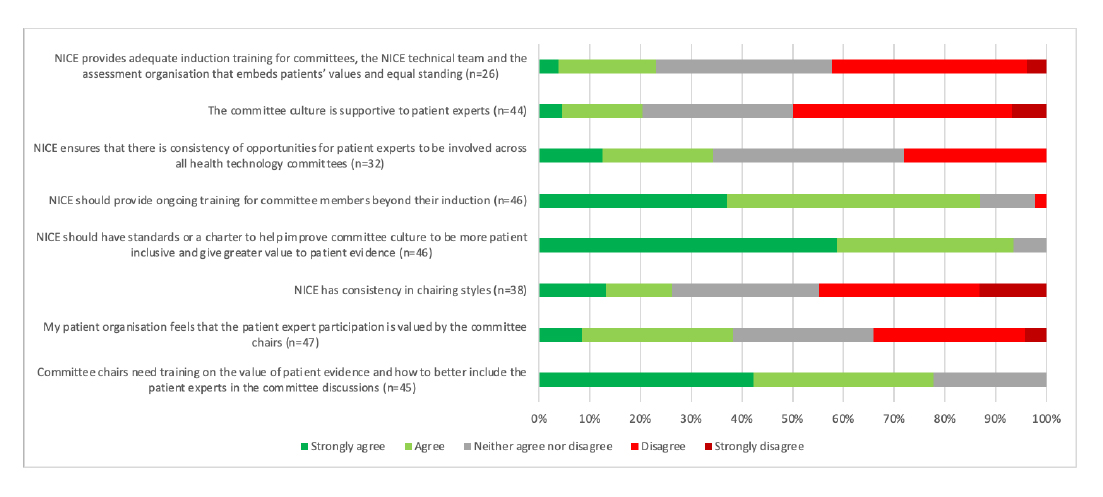

Committees are crucial and they need more training

Reflecting what is likely to be known by anyone who has regularly had to engage with Appraisal Committees and the personalities that can drive them, respondents have highlighted the culture of committees as needing further work. This specifically includes having standards or a charter to help improve the committee culture. The work that’s needed, according to respondents, doesn’t end there and includes the need for training both for general committee members, but also for chairs in particular (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Patient organisation respondents views on committees

Note: Data from NICE (Undated) Improving meaningful public involvement in NICE medicines and technologies guidance.

Need for more understanding of commercial access schemes

Not mentioned in the main NICE report but included as part of the data annexe, it seems that many respondents to the survey aren’t all that clear about the importance of commercial access schemes. Forty-nine per cent of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that they understand the importance of commercial access schemes. Fifty-two 52 per cent disagreed or strongly disagreed that they understand the patients’ role in commercial access schemes.

Missing information to put the survey results into context

The NICE report on the online survey doesn’t give some basic information that you’d expect to see. There is no clear start or end date for the survey for example. Hard therefore to wrap some context around the 52 responses without that.

There is also no clear discussion relating to response rates. Partly this is because the survey was promoted via different routes, including Twitter, so it’s hard to know who knew about it in totality. Yet an obvious number is missing; NICE shared the online survey via emails to the patient groups listed on their own NICE database. Yet there is no number given for how many patient organisations are on this in-house database. That would help illustrate the reach of the survey; if NICE has a list of 100 patient groups, 52 responding looks ok. If NICE has a list of 1000 patient groups, it really doesn’t.

Then there’s the issue of whether things are getting better, or worse, over time. That’s hard to know. There is another report available from NICE on patient involvement in Technology Appraisal – but again without a date, why do they do that? – that asked slightly different questions but on similar themes.

If NICE truly wants to learn about what is going well it’d do well to think about how to bring in some consistency both for what it asks patient organisations, but also a panel approach. Some patient organisations have been involved in NICE’s work for years and given pipelines, will likely be involved in the future, such as those working in blood cancer. This would also help NICE to evaluate the work it’s doing to improve things. Eighteen recommendations arose from the latest NICE work on public involvement alone and there were five in the earlier report. Given the significant resources that go in – both by NICE but also by the patients too – we need to assess what works.

Inevitably things change and a big change since the most recent patient organisation survey was run in July 2019 is the digital-first approach. NICE may need to refresh their thinking on how best to ensure engagement in an era of virtual engagement as the default.

Are the public the same as patients?

It’s not an issue unique to NICE, but there seems to be a working assumption that the public is covered off elsewhere, or perhaps that we’re all patients in some sense, either having been in the past or the future, if not today. That confusion is evident in the title of the NICE report on their work on engaging with patient organisations; they call it “improving meaningful public involvement in NICE medicines and technologies guidance.” Yet they are not one and the same; if anything, NICE has to play the role of the taxpayer – a key perspective when thinking about value for money in a tax-funded health care system – and whilst some of these will be patients today, many will not be. That might mean bringing in some real public perspectives, not just the interests of today’s patients who are, more often than not, seeking access to a treatment that will benefit them.

Tell NICE what you think!

The latest of these NICE user experience surveys is now open and is due to close by 16 July. That survey poses some key questions that will be relevant to patient organisations as well as other stakeholders, such as perceptions on NICE improving patients’ access to innovative treatments and interventions and on NICE understanding and using patient and public opinion in their work. Take ten minutes and let NICE know what you think.

About author

Leela Barham is a researcher and writer who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally, on the economics of the pharmaceutical industry. Leela worked as an advisor to the Department of Health and Social Care on the 2019 Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS).

Leela Barham is a researcher and writer who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally, on the economics of the pharmaceutical industry. Leela worked as an advisor to the Department of Health and Social Care on the 2019 Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS).