Never waste a crisis: Can a new life sciences strategy be forged in the heat of Brexit?

Andrew McConaghie speaks to UK pharma industry leaders about Brexit and what is needed to create a meaningful, long-term life sciences strategy.

Inevitably, Brexit will be the biggest issue – indeed preoccupation - for the UK pharmaceutical industry in 2017. Theresa May and her government are determined, however, that her term of office up to the 2020 general election won’t solely be defined by Brexit.

That’s why the government is trying to draw up an industrial strategy for all of the UK’s key sectors, including life sciences.

Life sciences minister Lord Prior says a new industrial strategy for the sector will be ready by the springtime – around the same time as the government triggers the Article 50 process of leaving the EU.

Theresa May is expected to finally reveal how her government wants to negotiate the UK’s exit in a key speech tomorrow - and provide some detail around what kind of Brexit it will aim for.

Ahead of this, I spoke to managing directors and market access leads at major UK pharma companies to find out where they stand on Brexit and the promise of a new industrial strategy for the sector.

Pharma determined to seize an opportunity

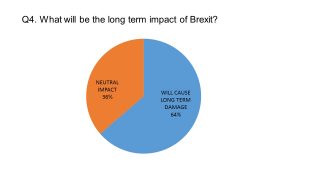

The pharmaphorum survey of UK pharmaceutical leaders conducted last month showed the majority of our respondents were pessimistic about the long-term impact of Brexit.

Nevertheless, in conversation with pharmaphorum, it is clear that all the UK pharma leaders were determined to make the most of any opportunities created by Brexit.

As Winston Churchill said, one should “never let a good crisis go to waste”, and Brexit certainly qualifies by that definition.

Roche’s UK Market Access Director Deborah Lancaster says the industry has to dispense with any gloomy ‘Eeyorish’ tendencies, and make Brexit work for the sector.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="100"] Roche's Deborah Lancaster[/caption]

Roche's Deborah Lancaster[/caption]

“We’ve got to try and make it positive. Rather than wait for everything to go to hell in a handcart we need to do something that’s going to make it work for us.”

Nevertheless, she stressed that there was a lot at stake, and that the company was keen to retain the free movement of people in to and out of the UK.

“We’ve got 36 different nationalities working in our head office in Welwyn, from all over the world, not just Europe, and that’s really valuable.

“Those people bring a huge amount of brainpower and different skill sets to our UK affiliate, and we’re equally keen that British employees can go and work in other affiliates abroad.”

Boehringer Ingelheim’s UK managing director Klaus Dugi says his company has created its own Brexit taskforce. He chairs this cross-functional group, which looks to mitigate risks and identify any opportunities arising from Brexit.

He believes there is a potential opportunity to create a faster approval process through the MHRA.

“The current EMA process needs to align 28 countries, and can be quite complex. So autonomy in decision making would give the UK at least the potential to bring innovative medicines to its patients faster.”

And yet, as exciting as a fresh start sounds, clearly pharma (and of course the government itself) needs to come to a clear position on what kind of Brexit it wants. So what kind of Brexit are UK pharma leaders hoping for?

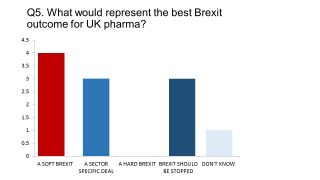

Our survey, conducted in December, found a Soft Brexit had the greatest support - and none supported a Hard Brexit.

Mark Hicken, Managing Director UK & Ireland at Janssen (J&J’s pharma division) is a member of the ABPI board, and has discussed this crucial question with his counterparts across the sector.

What does he think is the best option?

[caption id="attachment_23623" align="alignnone" width="270"] Janssen UK's Mark Hicken[/caption]

Janssen UK's Mark Hicken[/caption]

“In the absence of solid alternatives you would say the softer Brexit.” He states. “I think that’s a view that the industry took through the working group that was put together over the summer.

“I think, broadly, the industry view is that if we’re going to negotiate a position outside the EU, then we need to maintain as much of what we’ve got as we can.”

He adds that, beyond this, if there is a genuine opportunity for the UK to secure advantage, then it should consider those opportunities as part of these negotiations.

“Who knows how these negotiations are going to play out; it’s very difficult to predict.”

Nevertheless he concludes: “I think we’ve made clear what’s important – the movement of people, access to the single market and freedom from tariffs. And making sure the regulatory process either gets better or is as good as we have now.”

UK to remain a key launch market?

Another key question for the medium-to-long term is whether or not the UK remains an early launch market after Brexit.

“I think it’s too early to say,” comments Deborah Lancaster.

She says that while the country is a great place for conducting early research and clinical trials, the NHS remains ‘low and slow’ in its uptake of new medicines. Brexit will do nothing to ameliorate this problem, but is more closely linked with restricted funding of the NHS as a whole, and specifically for medicines.

England has fallen behind its European counterparts in terms of overall health spending as a proportion of GDP, and also in medicines expenditure. Figures from the ABPI suggest spending on drugs is around 1.0% of GDP, compared to 1.3% in Germany and Italy, and 1.4% in France (with US spending in first place at 2%).

“Obviously we’re really keen to maintain the investment in the UK in this affiliate; it’s whether or not we can, in all good conscience, recommend those investments if we know that we won’t be able to launch one of our medicines here.

“We all want the best for UK patients, so we’re desperate to get access for these innovations and yet for some of them are nigh on impossible."

A new Life Sciences industrial strategy

[caption id="attachment_5494" align="alignnone" width="200"] AstraZeneca's Lisa Anson[/caption]

AstraZeneca's Lisa Anson[/caption]

Lisa Anson is AstraZeneca’s President of UK, and takes up the post of President at the ABPI, the UK’s industry association, in April.

She says the promise of a new industrial strategy for life sciences is a major opportunity for the industry – and government – to seize. She believes the government can end the current fragmentation across policy and structures in life sciences and the NHS, and create one overarching framework.

“If we’re going to make the UK a great place for life sciences, everything needs to be connected; the NHS, the commercial environment, including uptake of new medicines, and R&D investment. I think the industrial strategy can provide a coherent framework to ensure the different parts work together, and create a medicines access environment that values, rewards and utilises the innovative outputs from R&D while addressing NHS affordability.”

Mark Hicken agrees, and say the concept of seeing the NHS as an engine for innovation is critical to this project.

“You can’t say let’s have a healthy, vibrant Life Sciences sector but, by the way, we still continue to attract 5-6% of global R&D and yet only generate 2-2.5% of global sales. That just doesn’t bear close scrutiny. So there’s got to be some alignment across these areas.”

The Office of Life Sciences (OLS), which bridges the Department of Health and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, is leading on the creation of this new vision.

The OLS also developed the Accelerated Access Review (AAR), which tried to create a ‘lit runway’ for new medicines in the UK. However it was a product of the former David Cameron government, and has been overtaken by Brexit events, so the new industrial strategy will supersede it as the blueprint for pharma’s future.

Mark Hicken says it is crucial for the government to see the NHS not just as a health service, but as an engine for innovation and prosperity.

“Are we funding a world-class healthcare system to deliver for the needs of the people in the UK as well as positioning the UK as a great place to come and research new innovations? That’s a fantastic opportunity for the government.”

The underlying message from across the sector is that greater investment in the NHS is not only good for the health of the populace, but also for life sciences. However as the ongoing winter crisis in the NHS shows, Theresa May is reluctant to answer NHS pleas for greater funding.

Market access issues

Mark Hicken says the NICE process is key to market access in England and Wales, and needs a root-and-branch review.

One issue is the mismatch between NICE’s technology appraisals and the separate pricing discussions.

“At the moment you are encouraged to provide NICE with a value assessment for each different indication for the same molecule, which is fair enough. But when it comes to the pricing conversation, you are not allowed to have more than one price for the same medicine.”

He says: “Of course that creates a risk of undervaluing some of the indications that you’re investing in.”

A new pricing and reimbursement strategy

As both sides are aiming for a comprehensive strategy, this would require linking up these NICE processes with the central pricing agreement, the Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS), which is due to expire in December 2018.

Many industry leaders have voiced their dissatisfaction at the current PPRS, which they believe hasn’t delivered on promises to promote uptake of new medicines.

[caption id="attachment_23621" align="alignnone" width="264"] Boehringer Ingelheim UK's Klaus Dugi[/caption]

Boehringer Ingelheim UK's Klaus Dugi[/caption]

"Ultimately, we would like to see the PPRS agreement working better for patients,” says Klaus Dugi. “This would mean that the many innovative new medicines, not only those in development, but those that have already been recommended for use by HTA bodies, can be funded and adopted by local NHS systems. This would be of great benefit to patients."

Of course the massive complexity of the Brexit process, and the limited time available to formulate a workable plan, is placing a huge burden on government. This is one of the biggest risks in 2017 and beyond, and will limit the capacity of Whitehall and ministers to negotiate with the sector on fine-tuning a new strategy – as always, fine details can make the difference between a functioning system and a chaotic jumble of disjointed initiatives.

There have been half a dozen strategic reports and initiatives aimed at supercharging UK life sciences over the last decade and, while most have contributed something, all have fallen short of high expectations - with a failure to truly link a change in NHS culture and funding with life sciences usually among the chief obstacles.

So is there any reason to expect this time will be different? While Brexit adds a new imperative to industrial strategy, it also adds huge complexity and uncertainty; not the ideal background for creating a clear vision for the sector. Meanwhile, Theresa May appears to be digging her heels in against calls for more funds for the NHS, even amid clear signs of an impending crisis.

This shortage of funds is hitting pharma directly: NHS England is behind a new move to add a new affordability measure to the NICE process, something being strongly opposed by the sector.

There is no doubt of the political will to help support a world-beating life science sector in the UK, however.

In her first speech as Prime Minister on 11 July, Theresa May said: “It is hard to think of an industry of greater strategic importance to Britain than its pharmaceutical industry.”

This is an encouraging signal for the sector - though the notion that the pharmaceutical industry in the UK belongs to the UK is questionable. Indeed, if May and her government choose to prioritise immigration controls ahead of economic considerations – which seems to be a possibility – the country might find much of its expertise, home grown or foreign born, could move to other markets.

Like another of the country’s world-class sectors, financial services, UK pharma will be making its demands crystal clear, and will be hoping that a workable compromise between economic requirements and political demands can be struck.