The first ever ‘artificial pancreas’ is here - the iPhone of insulin devices

Medtronic has become the first to gain approval for a 'hybrid closed-loop system' - a major step to helping automate insulin delivery for type 1 patients. Undoubtedly this is the start of an evolution towards a true 'artificial pancreas' which could transform treatment of diabetes.

The first ever device to automatically monitor blood glucose and release the right levels of basal insulin has been approved in the US.

Medtronic's MiniMed 670G hybrid closed loop system has been hailed as a long-awaited breakthrough, as many people with type 1 diabetes and their families have been calling for such a device for years.

The MiniMed 670G will be available for patients 14 years of age and older with type 1 diabetes from Spring 2017.

Medtronic and the US FDA shy away from calling the device an ‘artificial pancreas’ - patients still need to enter information about anticipated meals and instruct it to deliver bolus insulin doses. For this reason, the manufacturer is calling the device a ‘hybrid’ rather than a fully closed-loop system.

However patient organisation JDRF has embraced the ‘artificial pancreas’ term, and says the approval is the result of a decade’s research and development.

This is without doubt the start of a revolution in type 1 diabetes treatment and, maybe one day, type 2 diabetes as well. In terms of technology, however, the new MiniMed 670G is akin to the first ever iPhone - a breakthrough product which draws together disparate functions into one user-friendly device, but also one that will improve vastly as new versions and updates are launched. Also, much like the iPhone, the new device will carry a premium price, and US patients will be concerned that they may have to foot the bill themselves in order to acquire one.

Medtronic's closed-loop system got FDA approval... but will ins cover it, w/ only 5.6% imprvmnt to in-range BG? https://t.co/qDoJBUuFjr

— Kim / Diabetes (@txtngmypancreas) September 28, 2016

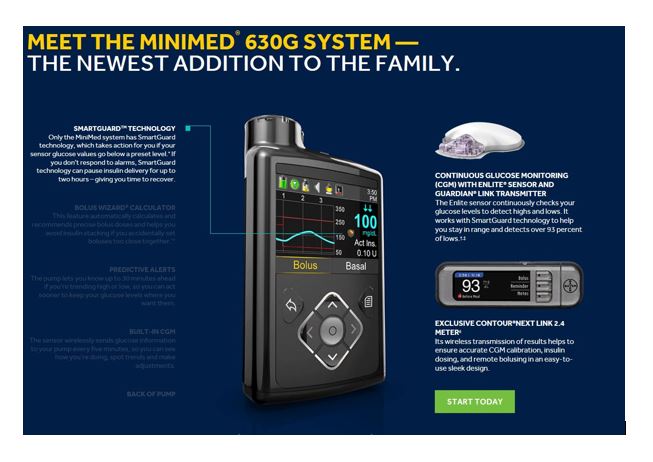

The MiniMed 670G includes a sensor attached to the body to measure glucose levels under the skin and an insulin pump strapped to the body. Attached to the pump is an infusion patch with a catheter that delivers insulin. While the device automatically adjusts insulin levels, users need to manually request insulin doses when they eat meals.

The FDA evaluated data from a clinical trial of the MiniMed 670G that included 123 participants with type 1 diabetes. The clinical trial included an initial two-week period where the system's hybrid closed loop was not used followed by a three-month study during which trial participants used the system's hybrid closed loop feature as frequently as possible.

The trial produced no serious adverse events, with no diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or severe hypoglycemia (low glucose levels) reported during the study.

Medtronic is, however, obliged to carry out a post-market study to better understand how the device performs in real-world settings. The company is currently performing clinical studies to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of the device in diabetic children between the ages of seven and 13.

"This announcement is a historic achievement for JDRF. After years of laying the ground work, this breakthrough is a testament to the reason JDRF exists – to help people with T1D lead better, safer, healthier lives while we continue on the path to cure and prevent the disease altogether," said JDRF chief executive Derek Rapp. "It marks a major accomplishment in one of our highest priority research areas."

However Medtronic won’t have the market to itself for long – Bigfoot plans to submit its rival product next year, with others such as Beta Bionics also in the race.

"This is a fantastic step forward, but we are not done. JDRF will continue supporting other artificial pancreas advancements and advocating for broad access to this life-changing technology," said JDRF chief mission officer, Aaron J Kowalski, PhD. "Several other technologies are in the pipeline that could also provide better outcomes and less burden for those living with T1D. Our work will not be finished until we cure and prevent T1D."

The development of the artificial pancreas is a case study in patient activism. Among the many spurring on development was Jeffrey Brewer, a technology millionaire whose son has type 1 diabetes. In 2004, frustrated with the slow pace of development in the field, he offered $1 million to the JDRF, challenging it to bring together researchers, manufacturers and the FDA to address obstacles and commit to the goal.

"JDRF's vision and leadership has been a critical catalyst to drive the field from a concept to today's reality," said leading Artificial Pancreas researcher Stuart Weinzimer MD of Yale University. "A decade ago, JDRF launched their Artificial Pancreas Project. This initiative dramatically accelerated progress by fostering collaboration among academic investigators in the field, industry, and other funding and advocacy agencies. I look forward to my patients benefiting from this very important advance."

Medtronic says it will need a little longer to launch the MiniMed 670G system, and expects the product to hit the market in spring 2017.

It says this timeline is necessary to have in place market and manufacturing readiness, payer coverage, and to train its employees, clinicians, educators, and customers on the new system.

One reason why Medtronic doesn’t call its new device an ‘artificial pancreas’ is that, unlike a real pancreas, it doesn’t deliver glucagon, the body’s natural counterbalance when insulin levels are high.

The JDRF’s Artificial Pancreas programme is working with Xeris Pharmaceuticals to develop a stable, liquid glucagon which would be compatible with pumps, which is in phase 2 testing.

Artificial pancreas devices would have the greatest impact if they were proven to help the far greater number of patients with type 2 diabetes. Small-scale studies in this population have been done, but wider adoption is likely to follow only when they are shown to be safe and effective in ‘real-world’ type 1 patients.

If Medtronic can demonstrate the device is superior in controlling diabetes, it could persuade health care systems to promote widespread adoption in type 1 patients. Medtronic is already claiming its devices improve outcomes – it says patients are four times more likely to reach their target A1C (blood glucose) levels. It also claims very significant reductions in complications such as damage to kidneys, eyes, nerves and the heart – and all with a 90% reduction in the number of insulin injections.

Meanwhile, there is already an energised and empowered group of type 1 patients and parents of children with type 1 who continue to push for access to better systems. Using the social media hashtag #wearenotwaiting, they have taken matters into their own hands and hacked existing devices to create DIY closed-loop systems. The most notable of these is the Nightscout Project, formed by parents who have hacked one digital continuous glucose monitor (CGM) to allow its data to be streamed to any device, and thereby help cut the risk of night time hypoglycaemia in their children.

Pharmaceutical companies in the insulin market have been noticeably at the periphery of developments, with only tentative investments in the field. The potential for these devices to be disruptive in the long term is real, however. This could see medical device companies and health care providers playing a bigger part in how insulin is used, a shift the pharma companies will have to anticipate to make sure they aren’t shut out of the new paradigm.