Access and elimination: the future of DAAs in hepatitis C

The dramatic improvements in safety, efficacy, tolerability and convenience from the first wave of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) have made a substantial contribution to changing both the treatment paradigm and the long-term prognosis for hepatitis C. Peter Mansell considers the likely path towards eradication.

The arrival of interferon-free, orally administered direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) in 2014 was a leap forward for the treatment of hepatitis C (HCV), a disease responsible for some 700,000 deaths globally each year.

Patients used to rely on injectable interferon-based combinations with success rates of around 50%, on average, depending on the specific viral genotype involved[1]. These drugs came with severe side effects, such as chronic fatigue, depression, diarrhoea or anaemia, which discouraged many patients from starting or completing treatment courses of anything from 24 to 72 weeks.

Rates of sustained virologic response with the new DAAs have now reached 95-99%, with few side effects, more patient-friendly oral administration, and treatment regimens lasting as little as 12, or even eight, weeks.

A rich R&D pipeline of second-wave DAAs could build on that achievement, with even more impressive efficacy, shorter treatment durations and better coverage of all hepatitis C genotypes.

Changing market

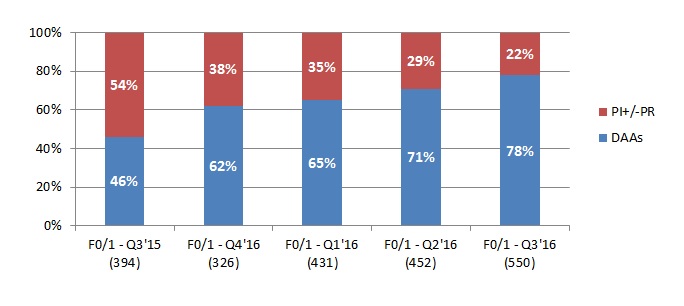

Research Partnership’s research manager, Conor O’Kane, has analysed the data collected by Therapy Watch HCV, an online study of patient record forms collected each quarter from 335 physicians across nine European markets and Canada. He offers some hypotheses about the future direction of the HCV market, which is now entering a new phase.

“As many doctors had previously ‘warehoused’ patients, in expectation of better treatment options, the initial entry of new-generation DAAs was characterised by pent-up demand for drugs priced at a significant premium to their predecessors,” O’Kane noted.

“Research we conducted in 2012[2] found that 56% of US patients delayed treatment intentionally, with half of them stating that this was because they felt they could not comply with the treatments available, or were contraindicated. Research conducted the following year among US physicians[3] found that 90% were intentionally delaying starting treatment until new treatments became available.”

In an effort to manage the additional costs of warehoused patients, health systems in Europe imposed restrictions such as budget caps (e.g. Spain, France, NHS England), confining access to patients with advanced disease, or insisting on eligible patients being free of intravenous drug/alcohol abuse. This was in line with measures taken by government healthcare programmes and private insurers in the US.

However, evidence from recent Therapy Watch data suggests that, having prioritised early usage of DAAs towards cirrhotic patients, EU5 countries are now adopting a more progressive, inclusive approach to HCV treatment. Germany has led the way in addressing patients with less severe disease, with F0-1 prescribing on the increase across the EU5. The most notable example is the UK, where 67% of patients treated for hepatitis C now have less severe F0-2 liver disease.

Source: Therapy Watch HCV data – Research Partnership

In this context, the dramatic improvements in safety, efficacy, tolerability and convenience seen with the first wave of DAAs have made a substantial contribution to changing both the treatment paradigm and the long-term prognosis for hepatitis C.

If an eradication strategy is really to take root, though, the emphasis needs to shift more decisively towards ensuring that key at-risk groups are identified and diagnosed. It must also ensure optimal access to the latest treatment options across all segments of the highly diversified hepatitis C population.

Aiming for eradication

The World Health Organization would like to see hepatitis C consigned to history as a major public health threat. In its first-ever Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis, the WHO set ambitious targets for “a world where viral hepatitis transmission is halted and everyone living with viral hepatitis has access to safe, affordable and effective care and treatment” [4].

Those included, by 2030:

- 90% diagnosis of viral hepatitis C infection worldwide;

- 80% treatment of eligible candidates with chronic hepatitis C;

- a 90% reduction in new cases of chronic hepatitis C infection;

- a 65% reduction in associated mortality.

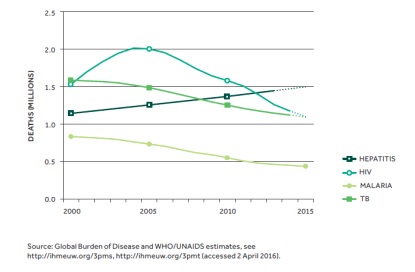

Worldwide, the hepatitis C virus infects an estimated 130-150 million people chronically each year4, with a 15-30% risk of liver cirrhosis within 20 years[5]. While there are indications that prevalence of HCV is declining in most developed countries, HCV-related disease and mortality continue to grow.

According to Dr John Ward, director of the Division of Viral Hepatitis at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, the 705,000 deaths attributed to HCV worldwide in 2013 marked an 84% increase on 1990[6].

Moreover, screening and treatment programmes for hepatitis C are complicated by factors such as lack of symptoms and marginalisation of some populations most exposed to HCV, such as prisoners, people who inject drugs, the homeless or people with HIV infection.

Estimated global number of deaths due to viral hepatitis, HIV, malaria and TB, 2000 –2015

Earlier is better

A growing body of evidence from clinical trials indicates that early treatment of hepatitis C produces better health outcomes[7].

O’Kane commented: “The Therapy Watch data suggest health systems are thinking more strategically about the benefits of more proactive HCV treatment. Higher upfront costs need to be weighed against the long-term consequences of delayed intervention, such as end-stage liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma and associated mortality.”

A genuine eradication strategy, though, also means extending DAA therapy to politically marginalised populations whose invisibility or lack of voice have made them easier to leave out of the treatment equation.

Some health authorities may be sceptical about treatment efficacy and persistence in populations with additional health and lifestyle problems. This may not be the case, though. For example, a phase 3 clinical trial of one recently-launched DAA in drug users on opioid substitution therapy found that cure rates were 91.5% – comparable to outcomes in the general HCV population[8].

At the same time, more inclusive treatment will require closer attention to large-scale screening for HCV, innovative models to improve access to care, such as pop-up clinics or telemedicine in prisons, and education, support and monitoring, including comprehensive follow-up mechanisms to prevent treatment lapses or reinfection.

With many more new HCV therapies arriving on the market, there will also be opportunities for health systems to drive down costs by leveraging competition to obtain significant discounts or rebates on list prices.

This is a strategy pharmacy benefit managers have pursued successfully in the US. Research Partnership’s market-access specialist Brett Gardiner noted: “With newer agents increasing competition and driving lower net prices, previously untreated patient populations are more likely to benefit from more widespread DAA penetration and relaxed authorisations from payers.”

Eradication = market exhaustion?

With most chronic conditions, therapeutic advances in disease management tend to be incremental, such as improved survival and quality of life in cancer or keeping cholesterol and diabetes under control.

An eradication strategy for hepatitis C, based on broader access to DAAs with markedly improved efficacy and tolerability, might suggest that these new products are on a fast road to market exhaustion.

However, in years to come new players will still be able to enter the market if they position themselves appropriately, such as catering to difficult-to-treat patients, or those who have failed treatment.

There will also be opportunities for products that reduce treatment lengths or offer other administration benefits. The treated patient pool will continue to expand as new products are introduced, accommodating more stages of the disease and market niches based on different HCV genotypes, as well as other factors such as viral load and co-morbidities.

References

[1] Webster D, Klenerman P, Dusheiko, G. Hepatitis C. The Lancet. 13 February 2015, Retrieved from http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(14)62401-6.pdf.

[2] Living with HCV: online patient research conducted among 300 HCV patients in the US in May-June 2012.

[3]Therapy Watch HCV warehousing study: online research conducted among 68 physicians in the US, November 2013.

[4] WHO - Global Health Strategy on Viral Hepatitis 2016-2021: Towards Ending Viral Hepatitis. June 2016. Retrieved online at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/246177/1/WHO-HIV-2016.06-eng.pdf?ua=1.

[5] WHO. Hepatitis C Fact Sheet. Updated July 2016. Retrieved online at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/.

[6] Ward, J. Abstract of presentation to European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) conference on New Perspectives in Hepatitis C Virus Infection - The Roadmap for Cure.23-24 September 2016. Retrieved online at http://easloffice.eu/events/paris2016/EASL-Paris2016-Programme-Book.pdf.

[7] When and in Whom to Initiate HCV Therapy. HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases/Infectious Diseases Society of America. Retrieved online at http://www.hcvguidelines.org/full-report/when-and-whom-initiate-hcv-therapy.

[8] Grazoprevir/Elbasvir Hepatitis C Treatment Works Wells for People Who Inject Drugs. Liz Highleyman. HIVand Hepatitis.com. 10 August 2016. Retrieved from http://www.hivandhepatitis.com/hcv-treatment/approved-hcv-drugs/5827-grazoprevirelbasvir-hepatitis-c-treatment-works-wells-for-people-who-inject-drugs.

About the author:

Peter Mansell is a freelance writer and journalist with more than 25 years’ experience in the health, pharmaceutical and functional food sectors.

For six years he was a journalist at Scrip. He subsequently edited OTC Business News and Nutraceuticals International, as well as being deputy editor of OTC bulletin.

As a freelancer, he has worked for pharma companies, trade publishers and healthcare agency clients.

About Research Partnership:

Research Partnership is a global healthcare market research consultancy. For more information visit www.researchpartnership.com

Read more from Research Partnership in this White Paper: