New NICE processes – same old problem?

Following two recent controversial public consultations, NICE recently updated its Guide to the Processes of Technology Appraisal. The Institute believes the changes represent a sensible response to the challenges it faces of increasing demand and the need to speed up its appraisals. But what are the implications for manufacturers and patient and professional groups?

Throughout the consultation process for these changes, beginning in October last year, NICE was explicit that the primary driver for the changes has been the ever-increasing capacity pressures it faces. Not immune from the ‘age of austerity’, it is being asked to do more with less. Despite its funding dropping from £77.3 million to just £58.5 million in 2016/17, the number of appraisals it is expected to complete has risen from an average of 30 per year in 2014/15, to 55 per year now.

That target is set to rise even further and NICE expects factors such as the rise of personalised medicines and the need to appraise medicines in multiple indications will drive it to carrying out 75 appraisals per year in order to keep pace with demand. Its four Appraisal Committees are already struggling to carry the load, so it is clear that new ways of working are required.

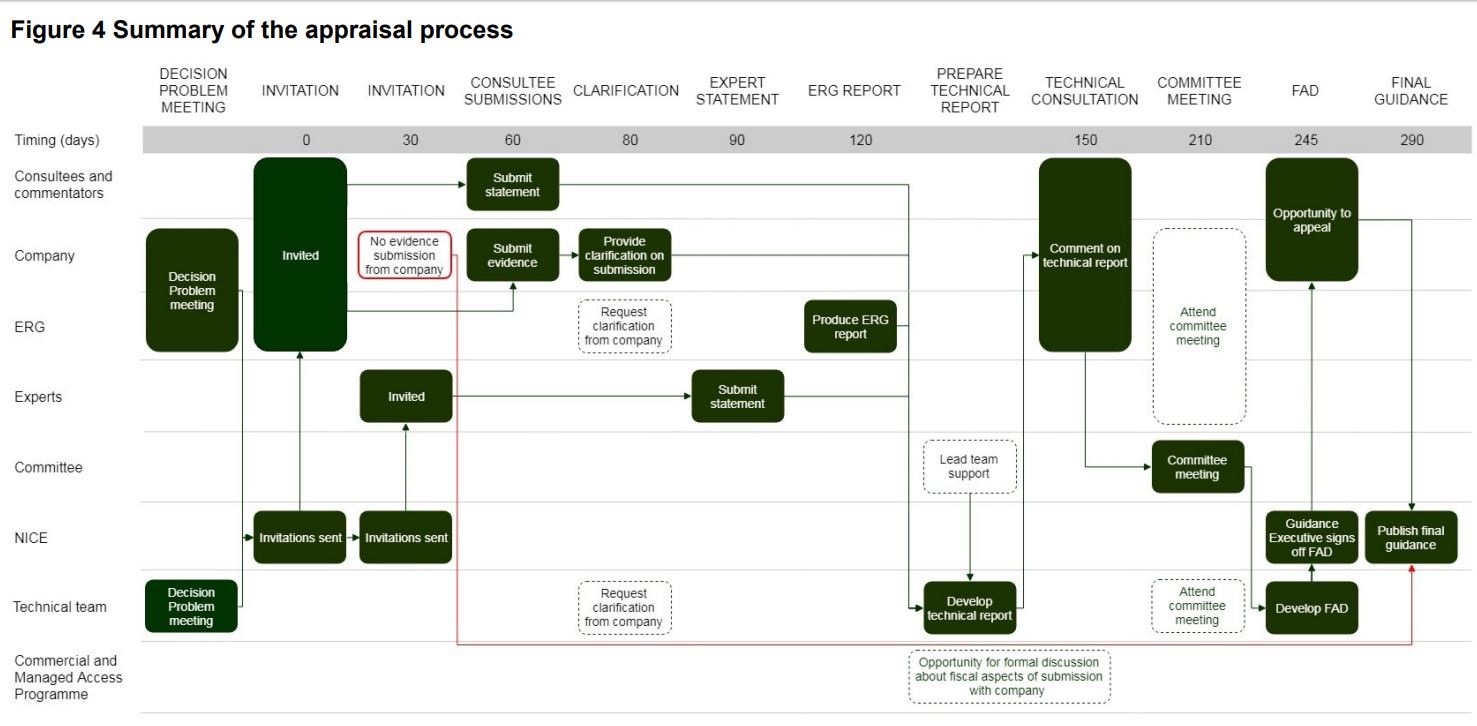

[caption id="attachment_43549" align="alignnone" width="1477"] NICE Appraisal Summary - please click on the picture for the full size image.[/caption]

NICE Appraisal Summary - please click on the picture for the full size image.[/caption]

The changes cover the single technology appraisal and fast track appraisal processes, plus NICE’s processes for the Cancer Drugs Fund and assessing budget impact. They are all about making the appraisal process as fast as possible without reducing the rigour and scrutiny that NICE applies in its assessment of each technology. Regulatory timelines will be more aligned, with companies asked to begin developing their NICE submission at the same time as they make their marketing authorisation application. The target is for all guidance to be published within 90 days of licensing, as is already the aim for cancer medicines.

Once the appraisal is underway, one of the most significant process changes sees the introduction of a new technical report stage, which will follow the production of the Evidence Review Group’s (ERG) report, but occur prior to the first Appraisal Committee Meeting (ACM). The technical report aims to identify and explore issues, come to preliminary scientific judgments, and advise the Appraisal Committee in its discussion of the evidence. It will be produced by a Technical Team, which consists of the chair or vice-chair of the committee, along with the NICE team (normally the associate director, technical adviser and the technical lead) and sent to consultees and commentators, as well as clinical and patient experts for comment. There are also more points throughout the overall process for formal discussions to take place with manufacturers over the ‘technical and fiscal elements of a submission’.

With the Appraisal Committee already briefed and advised by the Technical Team on the results of the Technical Consultation, it is hoped that the Committee should be able to consider more topics in a single sitting. The need for second and subsequent committee meetings could also be reduced with the committee Chair now having the power to issue a Final Appraisal Determination (FAD) if a company responds to an Appraisal Consultation Document (ACD) with an updated commercial offer that is to NICE’s satisfaction.

The changes have been broadly welcomed by industry. After all, protracted appraisals aren’t just bad for NICE, they’re bad news for manufacturers too, and most importantly, terrible news for patients desperate to access the latest new treatments. The new processes will by no means eliminate this problem, but a positive reading would suggest that having more opportunities for negotiations to take place throughout an appraisal, without having to go through repeated Appraisal Committee Meetings, should be welcomed by all. On the other hand, NICE is reinforcing the message to industry that faster appraisals means faster compromises on price.

Many patient groups have welcomed the ambition of these reforms, as faster appraisals they say will reduce uncertainty and anxiety for patients. Despite this, the proposals were initially met with revolt from patient groups, and no wonder. Having clumsily suggested in its first consultation that patient experts would no longer be required at appraisal meetings, the backlash that followed forced NICE to emphasise that this was never its real intention. Instead, patient group consultees will now be able to themselves choose to ‘opt out’ of meetings if they feel their views have already been adequately captured in the appraisal following the technical consultation. Nevertheless, this will require a change of approach for patient groups used to NICE appraisals; they will need to involve themselves more fully at an earlier stage; if they wait until the ACM, they may find it is too late for their views to be truly heard.

There are questions for NICE too. How much sway will the final technical report have with the Appraisal Committee or will the committee stage itself become simply a rubber stamp? And how will NICE deal with the problem of companies having to deal with even more immature trial data if appraisals are to start even earlier?

This final question goes to the heart of the issue as it relates to NICE’s core methodology and how it deals with uncertainty. The process changes are broadly welcome. While they will require everyone – NICE itself, industry, and stakeholders to adapt and up their games, in the main, they are really just sensible tweaks to timings, submissions and deadlines. What hasn’t changed is far more significant. NICE’s core methodology, in place since 1999, remains unaltered and, says industry, is as over-reliant on the QALY as ever. Many will see an opportunity lost that NICE recognised the need to be able to approve more innovative medicines, more quickly, but hasn’t given itself the tools to complete the job.

About the author:

[caption id="attachment_43553" align="alignleft" width="86"] Daniel Cambers[/caption]

Daniel Cambers[/caption]

Daniel Cambers is deputy managing director of the public affairs team at Four Communications, providing strategic counsel and applied insight to patient groups and some of the world’s largest pharmaceutical and biotech companies.