20 people who shaped healthcare in 2015 – part 2

In the second and concluding part of the review, Andrew McConaghie looks back at some of the most influential and interesting people in healthcare in 2015. From US biotech entrepreneur Elizabeth Holme to neurologist Oliver Sacks, the diversity of thought and talent is considerable.

| 11. Elizabeth Holmes | 16. Robert Duggan |

| 12. Martin Shkreli | 17. Jim O'Neil |

| 13. Doudna, Charpentier, Zhang | 18. Joe Cohen |

| 14. Andrew Conrad | 19. Frances Oldham Kelsey |

| 15. 'Mary' | 20. Oliver Sacks |

Elizabeth Holmes

In October Theranos, saw its promise to revolutionise blood testing and diagnostics start to crack under pressure.

Led by founder and chief executive Elizabeth Holmes, the company's vision is to transform blood tests by replacing needles with pin-prick samples taken from a finger. This promises to create faster and cheaper diagnostics for a wide range of diseases.

Theranos has been one of most highly-regarded US medical technology start-ups, but a Wall Street Journal (WSJ) expose found a far less promising picture.

The newspaper published news that the FDA had ordered the firm to stop using its Nanotainer tube – the proprietary miniature vial developed to collect blood for the tests, and a core part of its 'disruptive' technology.

The newspaper says Theranos is now operating more like a traditional lab, using the conventional needles to take blood from patients' arms. If the allegations prove correct, the hiding of this fact could amount to fraud.

The charismatic Elizabeth Holmes stands accused of misleading investors, and Theranos represents what many biotech investors feared in 2015 – the dynamic, privately owned company that turns out to be too good to be true.

Theranos epitomises the Silicon Valley 'unicorns', or unlisted start-ups valued at more than $1 billion – a term which contains more than a nod to the idea of people willing themselves to believe a fantasy.

Holmes says scepticism about the company is inevitable.

"First they think you're crazy, then they fight you, and then all of a sudden you change the world," Holmes recently commented.

The coming year will see the Theranos drama play out. The company may still change the world of diagnostics, but it is will almost certainly take longer than originally hoped.

Martin Shkreli

Somebody who has fallen even further than Elizabeth Holmes – and stands accused of peddling the grandest of fantasises - is Martin Shkreli.

The former hedge fund manager shot to infamy earlier this year when his company Turning Pharma bought the rights to the generic drug Daraprim (pyrimethamine) a treatment for HIV/AIDS related infection toxoplasmosis.

The decision to increase the price more than 50-fold in September caused outrage in the US and, despite promises to reconsider, Turing's price remained high.

For a time, Shkreli earned himself the epithet of 'most hated man in America' which spelled bad news for the entire US pharma sector, which saw itself tarred with the same 'price gouging' brush. Industry organisation PhRMA distanced itself from Shkreli (and Valeant), while biotech association BIO ejected Shkreli from its membership, but the sector nevertheless found it difficult to shake off the association.

Along with the Allergan-Pfizer tax inversion, the Shkreli episode has been hugely damaging for the sector in 2015, both causing much soul searching in the US public and the industry itself.

Then in early December, the saga took a new twist when Shkreli was arrested by the FBI and charged with "widespread fraudulent conduct" in relation to his former leadership roles at hedge fund MSMB Capital Management and biotech firm Retrophin.

Shkreli has now resigned from his position as chief executive of Turing and has been fired from his other CEO job, at Kalobios, which now faces financial ruin.

Whilst his misadventures in the world of biotech now look to be over, the damage he has caused to the sector and its reputation will not be easy to mend.

Jennifer Doudna, Emmanuelle Charpentier, and Feng Zhang

Jennifer Doudna, Emmanuelle Charpentier, and Feng Zhang are three scientists frequently cited this year, thanks to their work in one of the most exciting frontiers of biology: CRICRISPR/Cas9, the gene-editing technology.

Crispr/Cas9, is essentially a pair of molecular scissors which can edit DNA, which promises to snip out faulty genes associated with diseases, and simple replace them with healthy ones.

The field has seen enormous activity this year, with many pharma firms setting up research partnerships with the rival labs overseen by the three progenitors of the technology. There are, however, numerous obstacles. Alongside the considerable ethical questions about gene-editing, and the enormous technical challenges still ahead, there is also the question of intellectual property. Doudna, Charpentier and Zhang all have claims on the Crispr/Cas9 patent. This will need to be resolved in the coming years, but 2017 is expected to see the first drug using the technology enter clinical trials.

Read the latest on pharma's first forays into the field from pharmaphorum

Jim O'Neill

Former Goldman Sachs economics Lord Jim O'Neill is at the forefront of one of healthcare's most prominent battles: preventing an 'antibiotic apocalypse'.

If left unchecked, antimicrobial resistance (AMR), the development of drug-resistant bugs, could be a doomsday scenario. O'Neill's UK government funded AMR Review predicts a continued rise in resistance by 2050 could potentially lead to 10 million people dying every year and cost the world up to $100 trillion.

O'Neill secured one of his key goals in 2015 by securing a partnership with China to fight the problem. The UK and China will now work together to create a new global fund to stimulate the development of new antibiotics.

The partners aim to attract £1 billion investment to stimulate the essential research needed to tackle the problem, and launch the fund in 2016.

O'Neill is also proposing incentives to stimulate the development of new diagnostics – another crucial element in halting the spread of drug-resistant infections.

Read more on pharmaphorum

Andrew Conrad

Image: Verily

This year saw Google unveil a major reorganisation of its divisions, separating out its traditional tech and search engine businesses from other divergent divisions, such as its healthcare research enterprises.

Andrew Conrad is chief executive of Google Life Sciences (GLS), and the unit continues to push ahead with investments in a range of ambitious projects. The firm has built a multi-disciplinary team of doctors, engineers, chemists, and data gurus to return to some of the fundamental questions about health and the origins of disease.

This includes the hiring of leading neuroscientist Dr Thomas Insel, who will focus on mental health. In December the division announced a new name for itself – Verily.

Conrad said Verily will focus on shifting medicine from conventional medical technologies, "from reactive to proactive, from intervention to prevention."

Read more on Stat

Mary

As 2015 draws to a close, the end of West Africa's long Ebola nightmare looks in sight. Liberia was declared Ebola-free by the WHO in September, and Sierra Leone in November. However, Liberia has had new cases since the declaration, which mean the fight must go on there.

At the height of the epidemic in 2014, the developed world rushed to provide help for the three nations, but in 2015, the work done to finally eradicate the disease was carried out by homegrown health workers and volunteers.

These people have received little praise compared to their co-workers from developed nations, despite putting their lives at risk to help. To redress this, Doctors of the World have written this blog, putting a (fictional) name to one such worker – Mary. Read the blog here

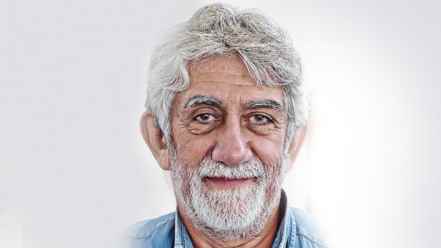

Robert Duggan

Robert Duggan sold biotech firm Pharmacyclics in May to AbbVie for $21 billion, earning $3.5 billion in the deal, one of 2015's most significant.

Duggan's story is remarkable: he knew nothing about the biotech sector when he first invested in the firm in 2004, but slowly built up his knowledge and shareholding in the firm as other deserted it. Duggan took over as chief executive and steered it to success with the launch of Imbruvica, an innovative treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. While in some ways a kind of 'chancer' who can bring the sector a bad name, Duggan's story shows how such opportunism and risk-taking can have positive outcomes for patients and investors alike.

Read the Forbes article on Duggan from March here

Joe Cohen

Image:GSK

Dr Joe Cohen spent 30 years working in research teams to develop a malaria vaccine, and this year saw the first ever product, Mosquirix, finally approved. The vaccine was developed by GSK in collaboration with the PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative, an NGO funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Trials were led by African scientists, with more than 15,000 children from across seven countries in Africa enrolled in the trial.

Mosquirix doesn't represent a final victory against malaria – trials showed it reduced episodes of malaria in babies aged 6-12 weeks by 27%, and by around 46% in children aged 5-17 months. Nevertheless, its approval is a major step forward against the disease, which infects around 200 million people a year and killed an estimated 584,000 people in 2013, the vast majority of these infants in sub-Saharan Africa.

Read the interview with Joe Cohen on the GSK website here

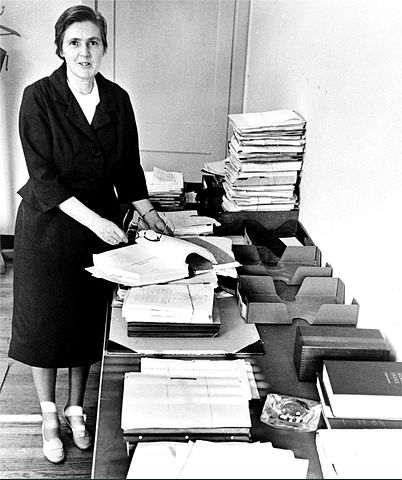

Frances Oldham Kelsey

Image: FDA

Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey, the most famous ever practitioner of that unheralded role, the drug regulator, died earlier this year aged 101.

Oldham Kelsey will forever be known for blocking the approval of thalidomide in the US, and thereby preventing the terrible birth defects caused by the drug, which had been developed as a treatment for morning sickness in pregnant women.

Born on Vancouver Island in Canada in 1914, she studied pharmacology at the University of Chicago and joined the US Food and Drug Administration in 1960.

Her job at the regulator was to evaluate applications for licences to market new drugs, a process that was far from well-established or held in high esteem at the time. One of the first filings to cross her desk was for Kevadon, the brand name chosen by the US licence holder of the drug, Merrell.

While European regulators had approved the drug in 1957, Kelsey and her colleagues at the FDA were suspicious of the claims made for the treatment when she first reviewed it in 1960. Kelsey delayed thalidomide's approval long enough for its terrible effects on unborn children to become clear in Europe, where thousands of children were born with deformed limbs.

Her instincts proved right, and the drug was eventually withdrawn around the world, with the US spared the disaster which hit Europe. News of her bravery and diligence reached the wider world via an article in the Washington Post, and she was hailed as a hero.

President Kennedy's administration then used the case to pass a new law in 1962 (the Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments) giving the FDA greater powers to require greater proof of safety and efficacy, full disclosure of side effects and generic names, and rapid withdrawal of unsafe drugs from the market.

Oldham Kelsey's actions paved the way for much more extensive checks and balances on drugs, and we now live in a much more safety conscious world today. But contrasting her era with today remains instructive. Her story reminds us that pressure on regulators to approve new drugs is a perennial factor - with the push to approve novel treatments always a compelling one. Balanced against this, regulatory science needs to evolve with medical science, but just how far and how fast is a difficult call. This is illustrated by this year's new 21st Century Cures Act, draft US legislation; this has generated hope of faster progress in approving new drugs, but also raised fears that existing safeguards could be eroded.

Read the New York Times obituary of Frances Oldham Kelsey here

Read the Science-Based Medicine article on the 21st Century Cures Act here

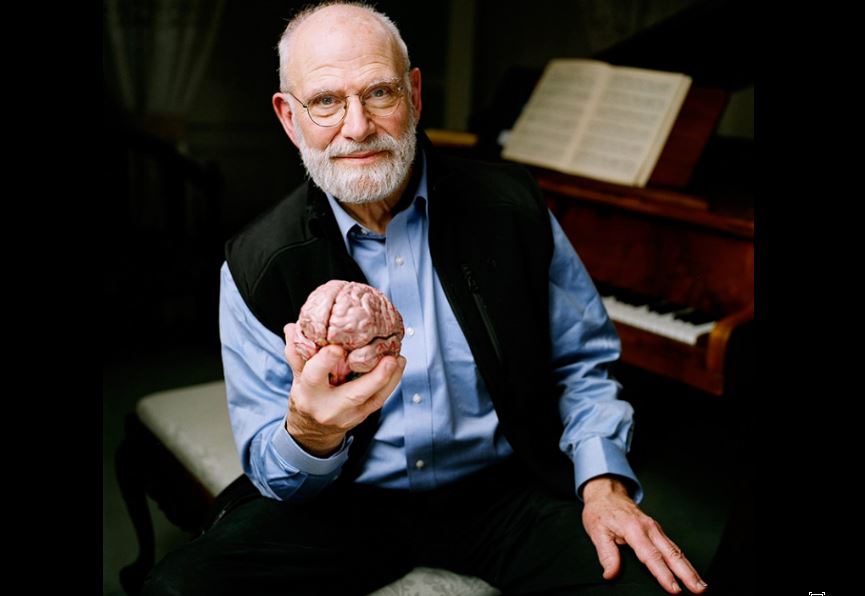

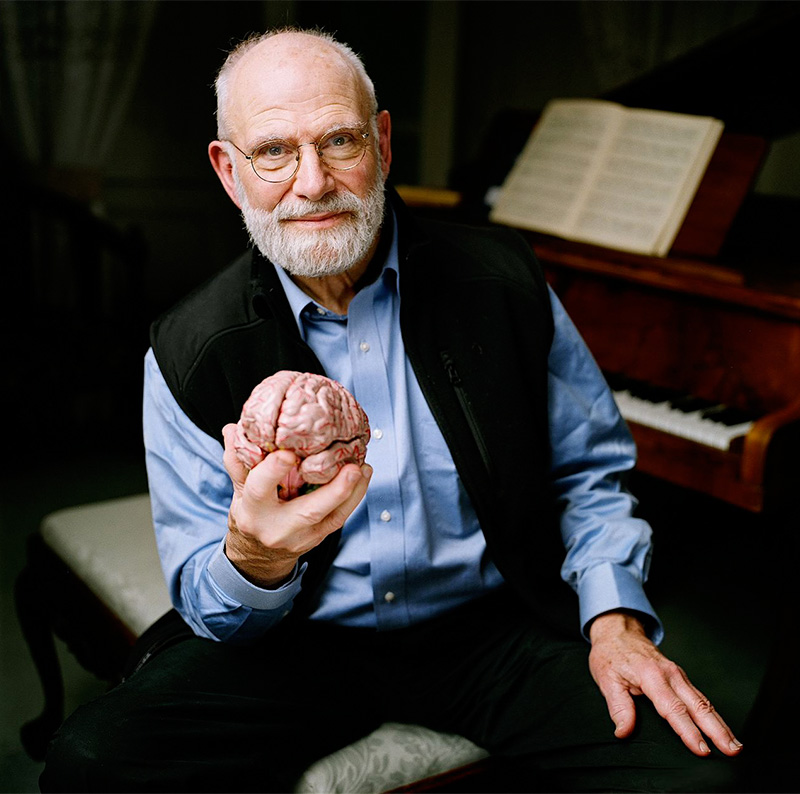

Oliver Sacks

Image: OliverSachs.com

The eminent neurologist, thinker and writer sometimes dubbed the "poet laureate of medicine" died in August at the age of 82.

The London-born polymath is best known for books, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, and Awakenings. The latter is a remarkable story of how a group of his patients were broken out of a frozen, catatonic state after decades locked in isolation. The patients, victims of an encephalitis epidemic from the 1916- 1927 period, responded dramatically to Sacks' use of the then-experimental drug, L-dopa. Sadly, the effect was only temporary, but the book and subsequent film were eloquent and strangely life-affirming studies of humanity.

Sacks had been suffering for two years from cancer, and as the end drew nigh, he published numerous moving essays on his life, death and mortality, published in the New York Times.

His insights into these subjects are of huge value and solace to a society increasingly dealing with old age accompanied by cancer and long-term illnesses.

Here's an extract from the essay My Own Life, published in the newspaper in February:

"I cannot pretend I am without fear. But my predominant feeling is one of gratitude. I have loved and been loved; I have been given much and I have given something in return; I have read and traveled and thought and written. I have had an intercourse with the world, the special intercourse of writers and readers.

Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure."