Social adverse event reporting - giving a voice to patients

This series examines five ways in which social media is having an impact on the pharmaceutical and medical device industries, focusing on how it can be harnessed to help traditional methods of patient engagement move forward. This second part looks at how patients are starting to passively report their adverse events (AE) online and what can be learned from this.

In my previous article exploring the impact of the hashtag on the healthcare industry I cited a US FDA-funded study into monitoring pharmaceutical products on Twitter. Of a convenience sample of 61,401 manually-categorised tweets 4,041 classified as Proto-AEs (posts with a resemblance to AEs).

As the study results suggest, passive reporting of AEs on social media has great potential in safety monitoring. The same study found that even though the classified Proto-AEs found in the Twitter data accounted for only 7.2 per cent of the convenience sample, there were nearly three times as many as the number reported to the FDA by patients. Furthermore, evidence suggests that '[e]ven within 140 characters, some tweets demonstrate an understanding of basic concepts of causation in drug safety, such as alleviation of the AE after discontinuation of the drug: "I found that Savella made my blood sugar [sic] high, once I got off, my blood sugar returned to normal"'.

Twitter is just the beginning. There are innumerable patient-centric forums, blogs, websites and social platforms where patients can share their stories and seek advice when experiencing AEs not listed in the product description. Such platforms can be a goldmine of information about the effectiveness of a new treatment and how it is being perceived by the target patient population, and may go some way to addressing the high percentage of side effects not reported. This has been estimated in some cases to be as high as 90 per cent.

As David Lewis, Global Head of Pharmacovigilance at Novartis, states, 'Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are grossly under reported by everyone, including healthcare professionals, but particularly so by patients [...] Mining data from social media gives us a greater chance of capturing ADRs that a patient wouldn't necessarily complain about to their doctor or nurse. Physicians are great at diagnosing illnesses and noting objective signs, but patients are great at reporting subjective reactions and feelings.' Indeed, patients are more likely to post anonymously on social media about more embarrassing side effects (constipation or erectile dysfunction) or even post on discussion boards about more general, ambiguous reactions (such as stomach cramps or headaches) than they are to go to their physician. This is all the more prominent when we take into consideration that six out of 10 Europeans go to the internet for health advice in the first instance.

What makes this method of AE reporting more exciting is that it is happening in more-or-less real time and can capture AEs after the trial period has ended. Furthermore, examining what patients are reporting as AEs of a treatment in real time can help to further explain the causes for current known side effects. As an example, when informatics company Epidemico was charged with monitoring synthetic glucocorticoid prednisolone and prednisone, patients taking it commented on social media about strong and persistent food cravings, often stating that they were 'feeling starved all the time'. On the other hand, the regulator's database only cited 'weight gain' as a potential side effect. In linking the two together we can see that if 'food cravings' were listed as a known AE and physicians could advise patients against overeating then the original AE of 'weight gain' could be negated.

As well as highlighting potential links between reported symptoms, companies can also use these patient reports to see where information isn't being made clear/available enough perhaps.

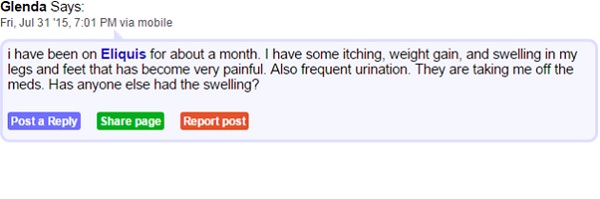

Consider the following excerpts from the patient forum medschat.com. Here we can see two individuals connected by a shared AE from taking Eliquis medication.

Though listed as rare, skin rashes, hives, itchiness and swelling are documented side effects of apixaban, the active ingredient in Eliquis. It seems there is a gap in the knowledge of both doctors and patients which is resulting in confusion and ill feeling towards the drug. In being aware of where this sort of confusion rises, healthcare companies can be sure to educate healthcare providers and patients from the outset on what to expect from a drug.

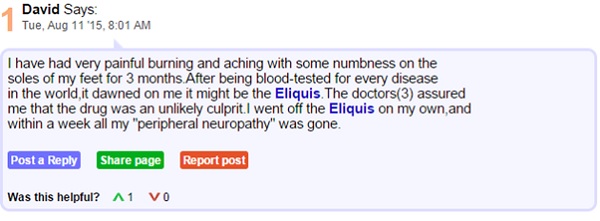

With an estimated 70 per cent of internet users being non-native English speakers it is important to remember the global implications of social AE reporting. As we will see in my upcoming article, language and culture can play a big part in not only how individuals describe their symptoms but also about how they go about reporting them. As such it is key that if health care providers wish to make the most of this form of social AE report they do not ignore non-English sources. The examples below are taken from Yahoo! Japan and popular Japanese Q&A site tell-me and both talk about a similar side effect of Loxoprofen.

In this example the user aadpg_dajpg is asking if drowsiness is a side effect of using Loxoprofen. They cite that they took some for a headache but have become so tired they have concerns about taking this medication at work. User fender_hiroaki responds they have tried to look it up but as far as they can tell drowsiness is not a listed side effect of using Loxoprofen.

In this example, taken from tell-me, user Momo is saying how using Loxoprofen makes her incredibly tired and is asking if anyone else has a similar problem. Judging from the style of language used and by the fact she has posted on other threads relating to universities and clubs, we can assume she is a younger user and this may mean she has different uses for Loxoprofen than the working-age individual in the above example.

These are just a few examples of Japanese speakers reporting severe drowsiness taken from a quick search of Loxoprofen on Japanese Q&A sites. In the vast majority of cases there seems to be little information available regarding the non-serious side effects of using the drug. Admittedly, the examples shown might be considered dated but they prove a valid point that social AE reporting is a global phenomenon and to truly benefit from the insights provided healthcare providers must consider a comprehensive language solution hand-in-hand with any social intelligence strategy.

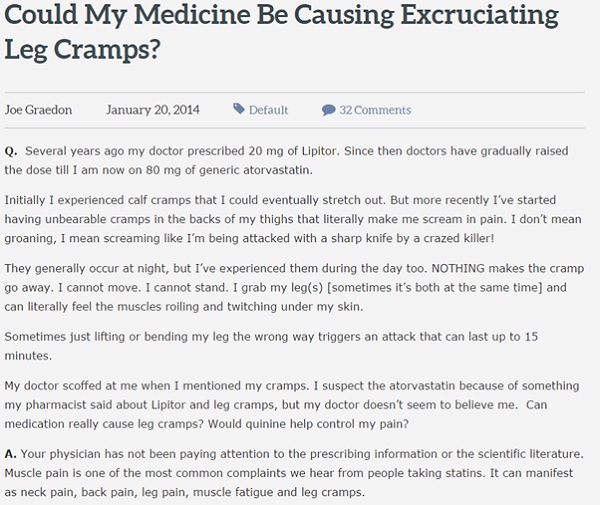

However, the use of social media in safety monitoring is not without its flaws. While the patient may be the best person to understand an AE they are experiencing, they are not necessarily the best at communicating it. The language on social media can often be colourful and dramatic, as shown below in this piece taken from the patient forum People Pharmacy. While the strong descriptions typical of social media postings may well be accurate, the danger of using this inherently exaggerated style is that it can lead to false reporting. As an example, someone will not usually complain of a mild headache on social media, but instead mislabel it as a migraine or use overly dramatic descriptions. As such AEs on social media are often subject to interpretation bias and extra care must be taken to ensure that the condition itself has not been misidentified. Often context is needed to fully interpret findings.

A further potential issue is that once a verified AE has been confirmed, how should the patient be approached and who is best placed to approach them and encourage them to make a formal report? Though the FDA does not recognise contacting posters on social media as part of its formal process, as part of its study Epidemico contacted many of those who were found to have submitted what was determined to be an ambiguous but serious event and asked if they would consider submitting a formal report. While most of the responses were positive, some objected to the idea of being contacted in response to their post, labelling it as 'creepy'. Despite this, however, it could be argued that once data is posted online it becomes publicly accessible and, as long as the person involved is contacted by a registered physician who is able to offer all the information and support, there should be no real qualms with reaching out to individuals online.

Further issues on this topic, and others faced in the other social applications covered in these articles, will be addressed in the final article of this series.

Ultimately, while the use of social media in safety monitoring cannot (yet, at least) be seen as an equal to traditional methods, it should be considered a worthwhile addition. At the very least, posts on social media can be seen as signalling potential AEs and highlighting them for further investigation.

About the author:

Leanne Orchard is a Language Solutions Executive in SDL's Life Sciences Solutions division.

SDL is a provider of language, technology and business intelligence solutions to international pharma and medical device companies and contract research organisations.

Leanne can be reached on lorchard@sdl.com or +44 (0) 1142 535 337.

Read the first part of this series: