The changing face of primary care in the UK

The complexion of Britain's primary care providers has changed beyond recognition in recent years, with the trend towards larger practices with responsibility for patients with more complex health issues. This means pharma must also adapt its approach in its interactions with them, finds Paul Mannu.

No-one can be unaware of the strains and tensions gripping primary healthcare in the UK, with frequent reports of sub-optimal care delivery, lack of resource, both in terms of cash and personnel, and the never-ending feeling that the current model of primary healthcare is simply unsustainable.

All of this is leading to the desire for change, and to actual change – in a real, fundamental way that perhaps we have not seen before. And, as with any change in the healthcare system, this is something with which pharma is going to have to get to grips.

NHS England's Five Year Forward View report makes it plain that the existing model of primary care cannot support a number of critical transformations in primary healthcare.

"Primary care is increasingly dealing more with treatment pathways of chronic care involving multiple disease states"

Perhaps the most challenging change is demographic: with an ageing population, primary care is increasingly dealing more with treatment pathways of chronic care involving multiple disease states.

At the same time, the demographics of GPs themselves are evolving. Older partners are retiring and fewer of their younger colleagues want to step into their shoes, preferring salaried positions or part-time roles in order to maintain a good work-life balance.

Now, more than half of GPs are female, and many of them quite rightly expect to be able to combine their careers with parenthood. In fact, GPs in general want a more flexible working environment which gives them time for family and play - and why not?

Meanwhile, patient needs are changing, driven by greater determination to move healthcare away from acute secondary services towards primary health, and by rising expectations driven by the patient centric mantra of modern healthcare, which exacerbates the current dissonance between the existing nature of primary health and its delivery.

And we can't ignore the economics of primary care. The ever-increasing costs of managing disease are not entirely the result of rising medicine costs, but rather of our increased knowledge and technologies which are enabling us all to live longer.

Framing the future

For once, professional bodies and GPs themselves are in agreement that structural change in primary care is essential if it is to remain free at the point of care (and this, we know, is always up for debate). Already three significant trends are emerging which are likely to frame the future:

1. Bigger is better

The days of small practices, with two or three partners, are numbered, with a move towards larger and even 'super' practices, whether in situ or via federations. Whilst the exact picture will vary according to local needs, the rationale behind this trend is common. The devolution of certain secondary services to primary care, alongside access to the provision of broader mental and social services, can only be resourced through the economies of scale of large practices, able to employ primary allied healthcare specialisms. As increasing numbers of partner-owned practices start to lose money, the unsavoury yet necessary premise of 'providing the cheapest primary care service possible' comes to the fore.

2. Division of labour

In effect, the current model still focuses on the GP as the central access point. But the professional competencies of other allied professionals, such as diagnostician, prescriber and manager are growing; similarly, pressure continues to grow to devolve some decision making to pharmacists who may be better able to make decisions for minor ailments. Meanwhile, GPs still want, ideally, to follow the patient's treatment pathway, and be autonomous practitioners and central points of access.

3. A different form of leadership

Leadership in primary care has often been cited as a missing ingredient (some might argue it's an easy cop-out as well!). Finally, there is an acceptance of the need, if GPs are to continue their primary role as clinicians, for someone to manage, triage more effectively and delegate aspects of patient care to reduce the burden on them. Whether this should be a GP or other healthcare professional is a contentious issue.

What does it mean for pharma?

First of all, the number of key decision makers is likely to reduce further. This means each one will hold bigger budgets, and will be juggling the medical, social and mental needs of the community. They will probably be handling more of the services previously provided by secondary care too.

For pharma, this means an increasing reliance on senior negotiating and sales skills with greater freedom to provide deals to larger stakeholder groups, and a broader understanding of the wider picture of healthcare needs.

"Too often sales calls focus on an assumption of episodic disease, while doctors are dealing with multiple disease states"

Much as primary care providers are already starting to do, pharma urgently needs to grasp the fact that the greater proportion of patients present with multiple chronic disorders. Too often sales calls focus on an assumption of episodic disease, while doctors are dealing with multiple disease states.

Added-value offerings and care management programmes will need to take this into account if they are to be meaningful to customers. This may mean greater collaboration with other companies in unrelated disease areas. It is also a great opportunity to consider appropriate algorithms of care that take consider the asset in different multiple disease states. For example, how does it perform when the patient is diabetic with heart disease or COPD? It may also reflect how pharma conducts clinical trials in the future and personalised medicines management.

Primary care should be the arena in which digital frameworks to improve healthcare access, information dissemination, the provision of monitoring and healthcare advice, really gain traction – but they remain underdeveloped. This is definitely an area in which pharma can help.

Medical records are progressively moving into a broader domain (eventually they will be available to the patient) and this will provide unrivalled opportunities to integrate digital monitoring of care.

Will we see the day when a diabetes video consultation service sponsored by a pharma company has helped ease the burden of management? When a patient uses an app to make a request, record, monitor and manage their own blood results? I would say yes, and pharma needs to be right there helping primary care providers to achieve just that.

Finally, a more existential change is happening to primary care. As larger practices take increasing responsibility for delivering what has, until now, been the exclusive domain of secondary care providers, the lines between the two will become increasingly blurred.

Pharma's current siloed focus on primary and secondary care must follow suit, otherwise our industry will be seen as increasingly disengaged from what is happening at the coalface of healthcare delivery – which is, increasingly, the primary care provider.

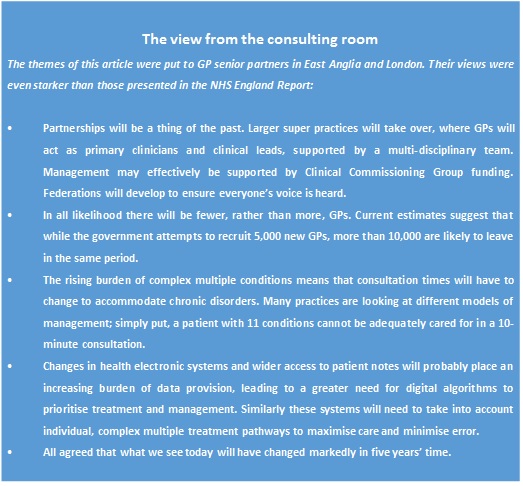

Box: Doctors' thoughts

The Author:

Paul Mannu is behavioural insights director at Cello Health Insight. He can be contacted at pmannu@cellohealth.com. Twitter: @pmannu

Read more from Cello Health Insight: