First human trials of lab-grown red blood cells start in UK

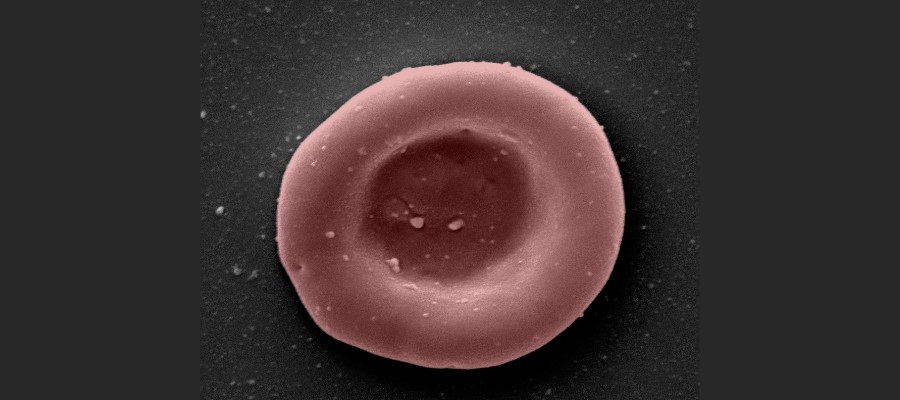

Blood cells grown in a laboratory have been given to people for the first time in a clinical trial being carried out by researchers in the UK, in the hope that plentiful supplies of rare blood groups can be manufactured to order.

A team from the universities of Bristol and Cambridge, NHS trusts and NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) have started giving small quantities of the lab-grown red blood cells – a couple of teaspoons full – to two healthy volunteers to see if they are safe.

The blood is made by harvesting stem cells from donated blood, which are then stimulated to expand and grow into large numbers of red blood cells in the lab – a process that takes around three weeks – until they are ready to be transfused into patients.

At the moment, it is a manual process, but the researchers hope to eventually develop an automated system that could routinely produce supplies of lab-grown material from blood donations for hard-to-transfuse individuals.

That could revolutionise the supply of rare blood types, for example, and assist in the treatment of patients with conditions like sickle cell disease and thalassaemia, who can sometimes require regular transfusions to control symptoms.

Lab-grown supplies would still rely on donated blood and would likely only be used in select circumstances, so there would still be a need for people to continue to give blood as they do now.

In the phase 1 RESTORE trial, the aim is to test not only the safety of the lab-grown cells, but also their lifespan in the body compared to infusions of standard red blood cells from the same donor.

The lab-grown blood cells are all fresh and selected to be in the same stage of development, so the investigators expect them to perform better than a similar transfusion of standard donated cells, which will have a mixed population of varying ages.

If the manufactured cells last longer in the body, patients may not need blood as often, and that could also reduce potentially hazardous iron overload from frequent transfusions.

The aim is to provide the 'mini-transfusions' to at least ten patients, each getting two at least four months apart, in this initial study, and much larger trials will, of course, be needed before the lab-grown blood could enter routine clinical practice.

Refinements to the process also need to be introduced, not least to extend the lifespan of the donated stem cells so they can produce larger numbers of red blood cells and make the lab-grown supplies more plentiful and cheaper to produce.

"This is the first-time lab-grown blood from an allogeneic donor has been transfused and we are excited to see how well the cells perform at the end of the clinical trial," said co-chief investigator Ashley Toye, professor of cell biology at the University of Bristol and director of the NHSBT unit for red cell products.

The trials start as blood supplies have fallen to a critically low level in England, mainly as a result of lower donations since the start of the pandemic and reduced staffing levels, and that could mean that some non-urgent operations may have to be postponed, according to a recent update from NHSBT.