NICE talking to you: Trends in early HTA engagement

With exclusive data from Freedom of Information (FOI) requests sent to the National Institute for Health and are Excellence (NICE), Leela Barham takes a look at the trend in early engagement with the UK's HTA body.

In 2009, NICE was one of the first health technology assessment (HTA) agencies to offer the opportunity for early scientific advice, at a cost. The fees range from £20,000 to £75,000 per project. They are based on cost-recovery.

The idea behind this service is help companies understand the agency's point of view on evidence; the gaps and how to fill them before the appraisal. Ultimately the idea is to help companies achieve patient access.

The NICE scientific advice service includes a standard approach (taking around 18 weeks) and an express scientific advice service (taking around 12 weeks). The standard approach offers the most in-depth option. Companies ask questions through the service, often on:

- Clinical trials, design and analysis

- Trial populations

- Outcomes

- Comparators

- Quality of life data

- Economic analyses (modelling, extrapolation, resource use and costs)

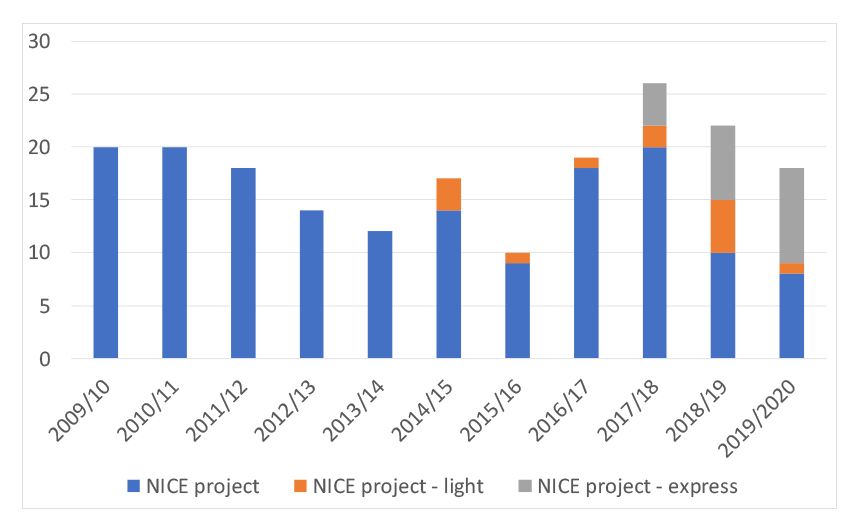

The service is popular; over the eleven years it’s been used on average almost 18 times each year although take-up has varied over time (see figure 1).

Figure 1: NICE early scientific advice projects, 2009/10 to 2019/20

Source: Data from NICE FOI responses. Note the light service has been incorporated into the standard service. Light was previously aimed at small and medium sized enterprises.

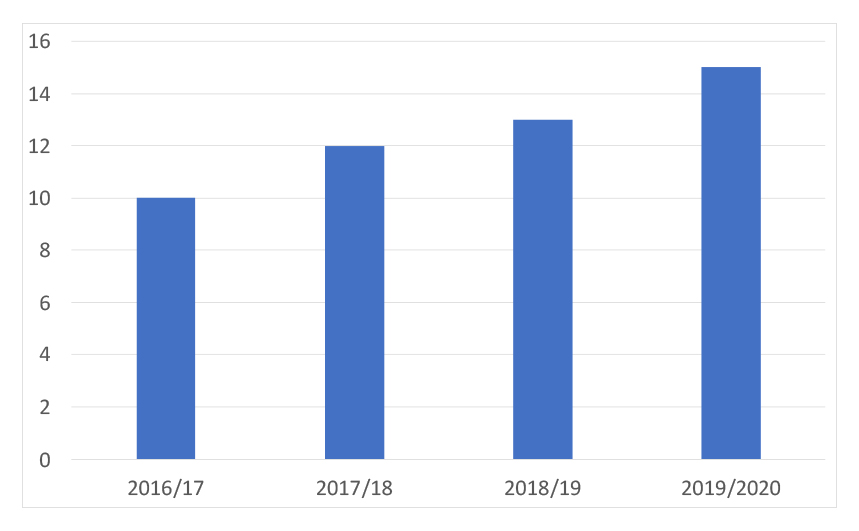

Since 2009 the agency has added further charged-for services; in 2015 NICE added the Office for Market Access (OMA). OMA can offer a safe harbour for discussions with NICE, NHS commissioners and other stakeholders. This has proven popular too and has seen a steady increase in safe harbour meetings held over time (figure 2).

Figure 2: NICE OMA safe harbour meetings, 2016/17 to 2019/20

Source: Data from NICE FOI responses.

By 2017, NICE added the Preliminary Independent Model Advice (PRIMA) service. PRIMA is a way to get the agency to check health economic models, taking either 12 weeks for the standard service, or eight weeks for an express service. The service was used twice in 2017/18, four times in 2018/19 and three times in 2019/20 according to FOI responses from NICE.

There are good reasons to want to engage PRIMA. Researchers analysed single technology appraisals completed in 2017 by NICE, looking specifically at technical errors and validation processes reported on the economic models submitted by companies. Only two STAs (5%) had no reported errors. Four STAs had more than ten errors (10%). That prompted Jeanette Kusel, director at NICE Scientific Advice, to highlight on LinkedIn the importance of the PRIMA service for checking models prior to submission.

Engaging with NICE, regulators and other HTA agencies

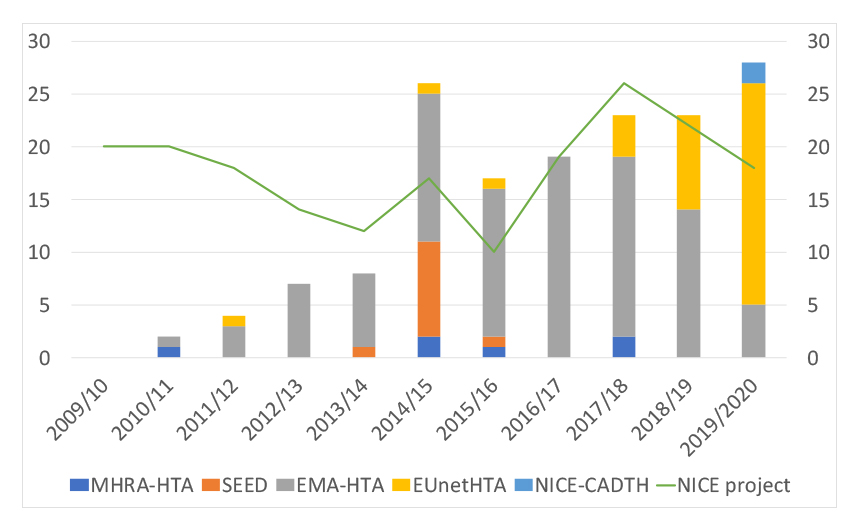

There are also other services that NICE can be part of in providing early advice. The agency has been a popular choice as part of the EUnetHTA early dialogue offer and has also been one of the HTA agencies taking part in EMA-multi-HTA early dialogues. With Brexit though, NICE has set up a concurrent scientific advice service for when companies want advice from EMA and the UK body at the same time. The latest option is with NICE and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH) together. The NICE-CADTH service was launched in 2019. It’s not had long enough to really get a track record, even more so when COVID-19 saw CADTH temporarily suspend the service.

Getting advice with NICE as part of the dialogue with others has proven to be more popular than talking to the agency alone (see figure 3). It’s not clear how far advice from NICE alone is a substitute for getting advice as part of a bigger conversation with others. It’s likely though that hearing from NICE on their own will give a depth of advice that might not be possible in the limits of a meeting held with several other voices in the conversation.

Figure 3: NICE early scientific advice projects alone and with others, 2009/10 to 2019/20

Source: Data from NICE FOI responses. Note: EMA-HTA includes NICE concurrent services delivered in parallel to EMA-multi-HTA dialogue.

What is the impact?

It is clear that the services to secure NICE advice are popular. The agency has a few testimonials on their website to support that. For example, for their scientific advice service, it quotes from a project feedback questionnaire:

“I truly value this Scientific Advice service... It creates fantastic opportunities for global drug development teams to better understand reimbursement hurdles and evidence requirements for timely market access. Great job!”

For PRIMA, the agency quotes Peter Wheatley-Price, market access and pricing director at Takeda UK, who said: “The Takeda team highly regarded the quality of the PRIMA reports and model review documentation. We appreciated the PRIMA team’s engaging and flexible approach at this pivotal stage in development and look forward to using the service as part of our model development efforts going forward.”

Yet it’s hard to know what difference they are making in terms of evidence strategies –what evidence will now be generated, and importantly for efficiency, what evidence won’t be generated because it won’t be valuable to the agency and payers in the UK – and ultimately, NICE recommendations. The services aren’t staffed by those who make the decisions later and it isn’t clear if Appraisal Committee members know if a company has sought advice, what that advice was, and whether it was acted upon by the company. There is a question over pull, through.

NICE has, so far, kept the details of which companies and which products have sought advice close to their chest. The various services offered are confidential and aren’t legally binding on both sides. Yet that doesn’t seem to explain why they can’t routinely release statistics about take-up of their services – it would be a real indicator of value if companies go back repeatedly for different products across their portfolios – nor why they can’t release details in the final guidance on whether advice was sought.

EMA does put into the public domain if a company has sought scientific advice and when. EMA keeps the details of the discussion out of the public domain. There is clear evidence that EMA scientific advice improves the chances of marketing authorisation.

Whilst companies who have sought advice from NICE will know the difference it has made or not, those companies who have yet to engage with the agency could be more likely to, if they know it can make a difference.

About the author

Leela Barham is researcher and writer who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally, on the economics of the pharmaceutical industry. Leela worked as an advisor to the Department of Health and Social Care on the 2019 Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS).

Leela Barham is researcher and writer who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally, on the economics of the pharmaceutical industry. Leela worked as an advisor to the Department of Health and Social Care on the 2019 Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS).